"Free" constructions are abundant in Algebra, and are actually examples of Adjunctions. Specifically, we have an adjunction:

Where is the free functor from the category of sets to this category of algebraic structures, and is the forgetful functor, which forgets the additional algebraic structure.

Usually, this universal construction is presented a bit differently, but is equivalent to the notion of adjunction.

As a concrete example, take Free Groups. Given a set , the free group is usually defined with a universal property:

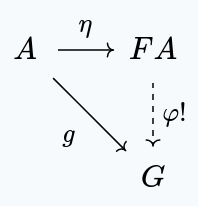

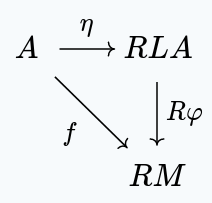

There is a group , and a set function such that for any other group and function , there exists a unique group homomorphism making the following diagram commute:

Of course, when talking about the interaction of morphisms and objects from , we really mean their images, under the forgetful functor . Being explicit, we get the following diagram:

We can characterize this object as being an initial object in the slice category (where is the functor sending every object to , and every morphism to ).

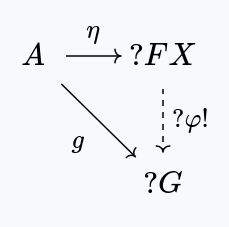

The objects consists of a choice of group and set function , and the morphisms are group homomorphisms making the following diagram commute.

It's clear that the initial object in this category is the free group , along with the morphism .

It turns out that this characterization is implied by the adjunction:

The "primal" characterization of an adjunction is that there exists a special binatural isomorphism between the two functors:

A more convenient (and entirely equivalent) characterization is that of two natural transformations:

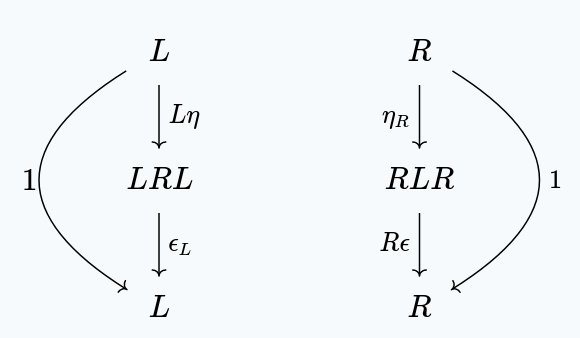

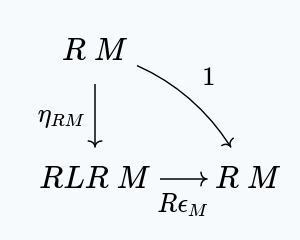

Satisfying these two relations:

which we call the left and right "zig-zag identities".

[!note] Note: I use the notation to denote the natural transformation whose component for the object is .

Similarly, denotes the natural transformation whose component at is .

With this adjunction in place, we can show that is the initial object in the comma category , for any object .

This is a fun series of diagram chases.

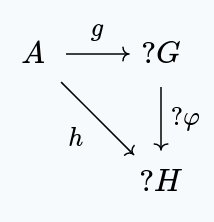

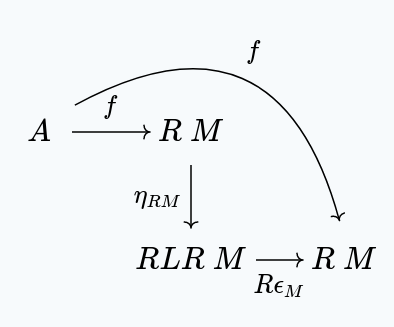

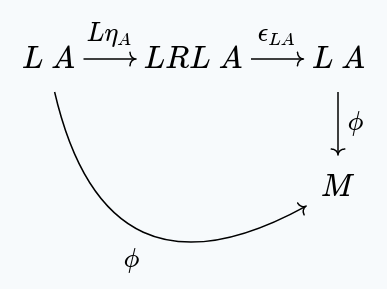

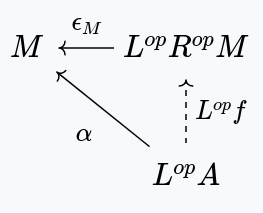

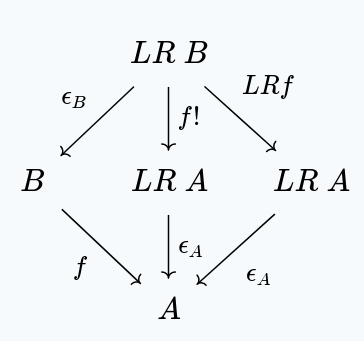

First, we show that there is a morphism to the other objects in the comma category. Given some other object in , we provide a morphism such that this diagram commutes:

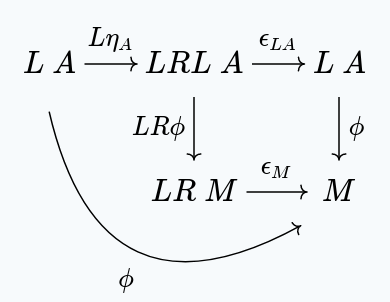

Applying the right zig-zag identity at , we get this commuting diagram:

We can compose this with to get:

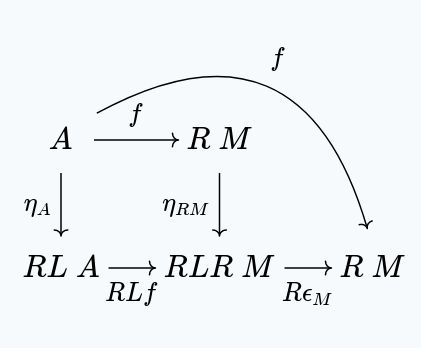

But then, by naturality of , we have:

And then is our . Since is a functor

[!note] Note: In the specific case of a free group, works by preserving all of the free algebraic operations we've created, but swapping out the "seeds" we've used. Then we interpret these free operations as concrete operations in , using .

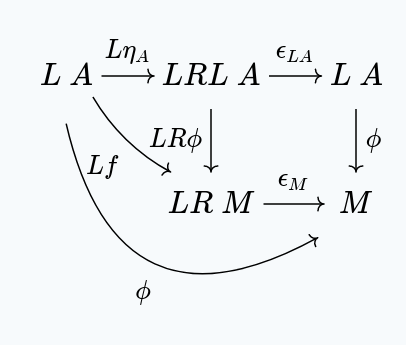

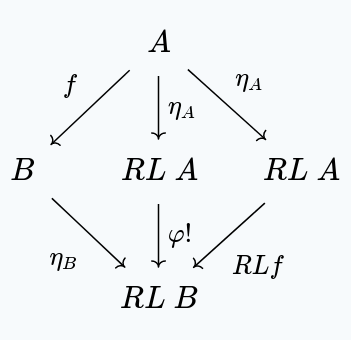

Next, we show that this function is unique. In other words, if with , then .

We start with:

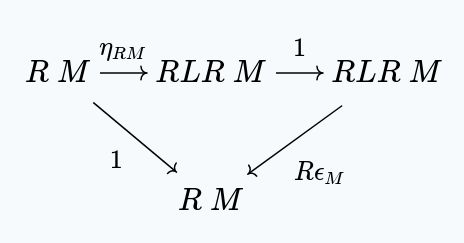

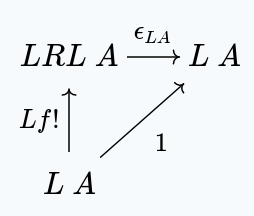

Then, we apply the left zig-zag identity, to get:

By naturality of , we get:

But, since , we have:

But, by definition , giving us:

In other words .

If we take the opposite functors and , we have:

Using our previous result, we get that for any object in , is initial in the slice category

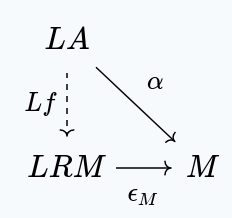

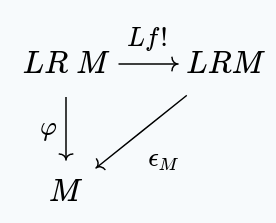

Of course, this is the same thing as saying that is terminal in the slice category . In other words, for any object in , with a morphism in , there exists a unique such that this diagram commutes:

Back to the example of free groups, we have the following situation:

Ultimately, this just expresses the fact that a group homomorphism out of a free group consists first of replacing each of the seeds with an element of , and then reducing the free algebraic structure using .

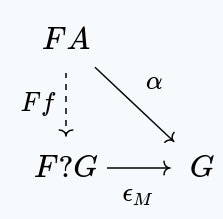

We can also go in the other direction. Let , be functors. If we have parameterized functions (which we don't yet assume to be natural) for any object in , and for any object in , such that is initial in , and is terminal in , then we have an adjunction:

First, is natural:

The right and left triangles both commute, since they make use of the unique that must exist whenever we have a function , for some .

Secondly, is natural:

The left and right triangles both commute, making use of the universal property of . (The argument is similar to before, of course).

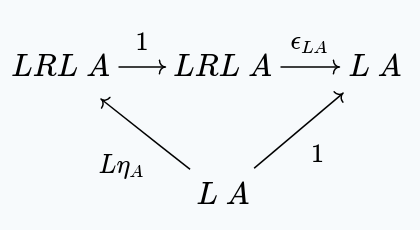

Now, for the zig-zag identities.

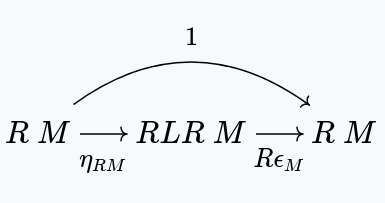

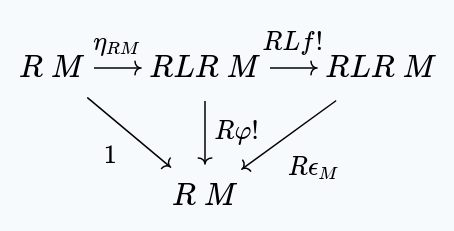

Let's start with the right zig-zag identity, for some object :

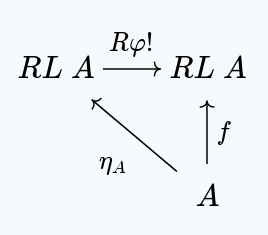

If we take , we have a unique such that:

by the universal property for .

For any , we have a unique such that:

by the universal property for .

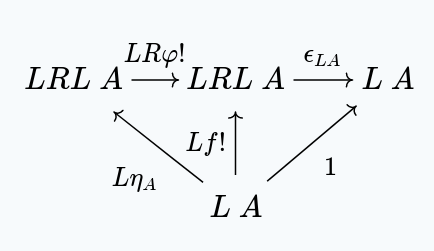

Combining the first diagram, with the image under of the second, we get:

But, satisfies the universal property of , which is unique. This means that .

We then have:

But clearly, satisfies the universal property of in this situation, which means . This gives us:

And so the right zig-zag property is satisfied.

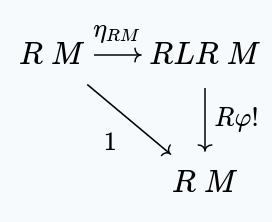

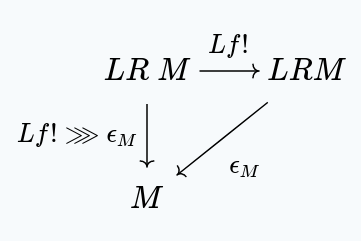

For the left zig-zag property, we use the same strategy.

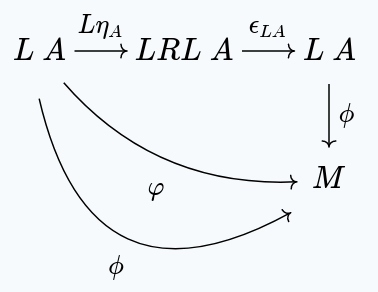

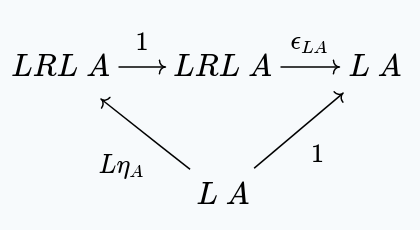

Given any object , in we want to show:

We have the following diagram:

With the unique satisfying this diagram existing because of the universal property of .

Similarly, for any , we have:

because of the universal property of .

Combining both diagrams, we get:

A similar argument as last time shows us first that , and then , giving us:

and so the left zig-zag property is satisfied.

Given functors and , these statements are equivalent:

In this post, I only proved . by definition, and is well known.