The standard definition of a topological space is in terms of open sets. We fix a collection of sets that are open by definition, and have a few laws about the structure of this collection.

One motivation for Topology is the study of sequences generalized as much as possible. You can define sequences very generally as functions: for a space , and study their convergence in this general setting.

One problem with sequences is that they're not sufficient to completely characterize topological spaces. For example, take the two following theorems:

If a space is Hausdorff, then every sequence converges to at most one point.

If there is a sequence inside a subset converging to , then is a limit point of .

We'd like to see if these statements hold in the other direction, but unfortunately, sequences are too constraining here, and we cannot prove the converse of these statements generally. We need to make assumptions about the structure of the space if we want to prove these things

Nets generalize sequences, and allow us to more fully characterize topological spaces. A sequence is just a function , giving us a linear sequence of points in the space:

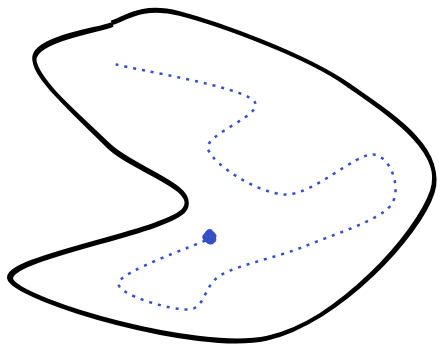

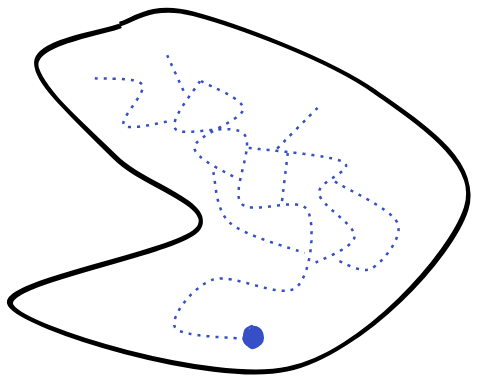

Nets generalize this by allowing threads of points that can temporarily diverge, so long as we have some kind of forward direction:

Formally, a Net is a function , where is a Directed Set.

A directed set is a partially ordered set with the following extra property:

For any points , there exists , with and . We call this being forward directed.

A partial order on a set is a relation satisfying:

(Transitivity)

The crucial property of being forward directed means that we can't have multiple "tails" diverging off:

instead, these tails always meet back eventually. This is because we can take any two points on these different tails, and there will be some point that succeeds both of them.

Formally, given a Net , a tail is a set of the form:

This consists of all points in the net that come after a given position.

It's clear that is a directed set, under , so sequences are also Nets.

Another good example of a directed set consists of a collection of sets that is closed under pairwise intersection. We have precisely when . This is forward directed, since given and , we can take as their common successor. Because the set is closed under pairwise intersection, this is also an element of the collection.

We can generalize this to collections of sets where for any , there exists with:

An example of such a collection would be a basis for a given topology.

With this in hand, we can define convergence of a net.

A net converges to a point precisely when every neighborhood of contains a tail of .

More concretely, this says that for every open set with , there exists a position , such that for all , .

We can now complete the statement we made earlier about Hausdorff sets.

A space is Hausdorff precisely when every Net converges to at most one point.

Proof:

(This direction can be done with sequences)

Assume is Hausdorff. We show that if is a Net converging to , then if , we must have .

Assume , but . Because is Hausdorff, we have disjoint neighborhoods and . Since converges to both and , we have a tail and in each of these neighborhoods, respectively. The points and are in the respective tails, and must have a common successor, , by definition of a Net. This point is in both tails, and must therefore be in both as well as . This contradicts the fact that .

Therefore, .

(This direction cannot be done with sequences)

Since is not Hausdorff, we have points such that every neighborhood also contains . We need to construct a Net converging to both.

Consider the directed set of neighborhoods of , . This is directed by virtue of being closed under finite intersection. We have precisely when .

Now, create a function by picking a point for each neighborhood. Each neighborhood is nonempty since it must at least contain itself, so this is well defined, assuming choice.

It's clear that this converges to , since any neighborhood of contains the tail .

Now, any neighborhood of of is also a neighborhood of , so it also contains a tail.

Therefore, converges to as well.

Note that this doesn't work out for sequences, because we don't have a freedom to construct a net that conforms so well to the structure of our topological space. If we can make assumptions, such as the neighborhoods around the point having some kind of countable structure, then we can recover this property.

Nets allow us to work in this general setting though.

As a reminder, a limit point of a set is a point such that every neighborhood of intersects .

Nets allow us to more precisely capture the nature of limit points better than sequences.

A point is a limit point of precisely when there exists a net in converging to .

(This direction works fine with sequences)

Every neighborhood of contains a tail in (by convergence), and thus a point in .

(This direction doesn't work, since we can't always summon a sequence with the desired properties)

Take the directed set of neighborhoods . Because each neighborhood of intersects with , we can define a Net . This Net obviously converges to , and is contained within .

In a metric space, compactness is equivalent to every sequence having a convergent subsequence.

We can generalize this beyond metric spaces using Nets, but we first need to define sub-Nets.

With sequences, the idea is that we take an increasing subset of the indices that never ends, and use that as our subsequence. With Nets, we need to take a directed subset, and also make sure that it never ends.

Given directed sets and , a cofinal map is a function , such that:

The first property just says that the inclusion from to can't completely obliterate all the properties of a directed set, which would give us subnets with a completely different structure.

The second property prevents us from "cheating" by taking an infinite net, and taking just a finite subnet. There always elements in the subnet succeeding us.

Concretely, a subnet of is the composition of with a cofinal map .

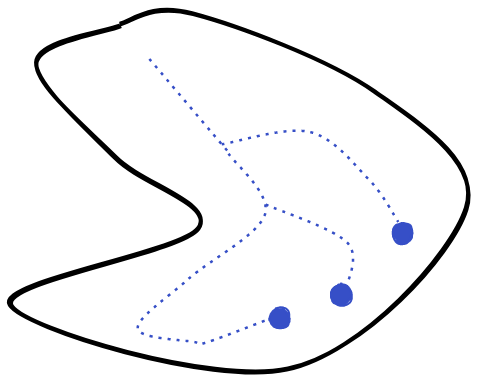

Before we get to compactness, we first need to develop the notion of an Accumulation Point.

Formally, an Accumulation Point of a net is a point such that for every neighborhood , and position , there exists an , with , such that .

Theorem: a point is an accumulation point of precisely when there is a convergent subnet .

Proof:

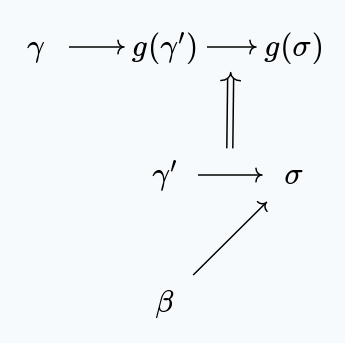

if , then we have, by definition of convergence:

Now, given some , and some , we need to find with .

Consider this diagram:

By the property of a subnet, we have some with . Then, we can use the forward directeness to get a . Since preserves the partial order, we have . Finally, since follows , we must have .

Thus, we pick

This other direction requires us to construct a convergent subnet, using the fact that is an accumulation point.

We first define a directed set:

We define:

That this is a partial order is straightforwardly proven. For forward direction, take and .

is also a neighborhood of . There is a with and . By definition of an accumulation point, we have a with .

Thus is our forward.

From this directed set, we can define a cofinal map:

This obviously preserves ordering. As for cofinality, if we have , then projects down to , and obviously .

(this is in fact a bit stronger than cofinality)

We now show that this subnet converges to .

Let be a neighborhood of . Because is an accumulation point, such that . The position is then the start of a tail of .

If , then , so this tail is indeed contained inside of .

Equipped with this key connection between accumulation points and convergent subsequences, we can prove that a subspace is compact precisely when every net in has a convergent subnet.

As a reminder, a subspsace is defined to be compact when every collection of open sets covering has a finite sub-collection covering .

An equivalent characterization of compactness is:

A subspace is compact precisely when for every collection of closed sets with the finite intersection property, the intersection of the collection is non-empty.

A collection has finite intersection property iff finite intersections of its sets are non-empty.

Proof:

We assume that our space is compact, and we consider an arbitrary net .

Consider the set of tails:

This set has the finite intersection property. If we have: , then this is the set:

By forward directedness, ther always exists a succeeding both and , so this set is non-empty.

By compactness, there exists a point in the intersection of all of these tails. This means that there exists a , with .

But this means that is an accumulation point, for if , and , then .

This is equivalent to there being a subnet of converging to , as we've previously shown.

Consider an arbitrary collection of closed sets with the finite intersection property. We want to show that is non-empty.

Define as the collection of finite intersections of sets in .

is obviously closed under finite intersection, and so is a directed set under , as we've shown earlier.

Now, by assumption, each element is non-empty, so we can define a subnet by picking a point for each set.

To show that is non-empty. We need to find , such that , for an arbitrary in this collection.

Let be an accumulation point of , which exists by assumption, and . We now show .

Assume , then is a neighborhood of , since is closed. Now, since is an accumulation point of , and there must be a with . But, we also have . This is a contradiction.

Therefore, we conclude that .

We've now shown that the intersection of an arbitrary collection of closed sets with the finite intersection property is non-empty, which shows that our space is compact.

So, we've seen that nets are sufficient to characterize quite a few topological properties. The cool thing about nets is that you can construct nets that mimic the structure inherent to any topological space.

In fact, knowing which nets converge is a complete characterization of a topological space.

A criterion is a mapping from nets and points to truth values , such that , for any subnet .

Evidently, a topological space induces a criterion, because convergence is defined for any topological space.

More surprisingly, we can use a criterion to induce a topology on .

First, note that we can equivalent define a topology in terms of its closed sets. We require that and are closed, the the finite union of closed sets is closed, and finally, that the arbitrary union of closed sets is closed. We can go from a closed topology to an open topology by taking the complements of sets.

A criterion induces a closed topology on , by defining a set to be closed precisely when for every net in we have

It's common knowledge that closed sets contain their limit points, and this characterization of closed sets inspires this definition.

We now show that this is a closed topology.

Now, since every is in , then is obviously closed.

Now, is always false if , since it's impossible to even ask this question.

Intersections:

If you have some collection of closed sets , if is a net in , then is also a net in any . then implies , by assumption, and thus .

Union:

Let's say we take , and a sequence converging to . Define the restriction:

If is not co-final in , then there exists some , such that for all , .

This would mean that the tail is contained in , and that is cofinal in .

Without loss of generality, assume that is cofinal. This provides us with a subnet of entirely contained in , by only keeping the points of the net in . This subnet converges to as well. By assumption, is closed, so .

Hence, .

We could also define open sets directly, by saying that a set is open precisely when no net outside of can converge to a point inside of . This is just a reformulation of what we've said so far.

One remaining question is whether or not applying this construction twice gives you the same result.

A topology gives us a criterion for convergence to a point. Does the induced topology equal ?

Yes, simply because a closed set is completely characterized by the fact that it contains its limit points. We've shown that a limit point is just a point with a net converging to it. Our induced topology marks every set containing its limit points as closed, which matches are original topology exactly.

Now, if you have a criterion , then you have an induced criterion: by considering the usual convergence, but under the induced topology .

It's pretty easy to show that , but I haven't yet been able to prove the converse.

It seems that in Kelley's General Topology, a few more axioms are required, and they might be able to patch this up.

The formulation of a topology in terms of a criterion invites generalizations. For example, you might relax the forward directedness and see what wacky spaces come out. You might also strengthen the conditions on the indexing set, and see what kind of strong properties of the space arise.