This is a technique to efficiently calculate the x coordinate given the x coordinate of a point on a Montgomery curve . This method is also easily implemented in a constant-time way.

This works for curves:

Satisfying .

The ladder itself

func ScalarMul(n Scalar, x Field) Field {

nP := Projective{1, 0}

n1P := Projective{x, 1}

swap := 0

for b := range n.msb .. n.lsb {

swap ^= b

condSwap(swap, nP, n1P)

swap = b

nP, n1P = step0(x, nP, n1P)

}

condSwap(swap, nP, n1P)

return nP.X / nP.Z

}Implementing the individual step:

// In field elements of course

const A24 = (A - 2) / 4

func step0(x Field, nP, n1P Projective) (Projective, Projective) {

double_X := nP.X + nP.Z

double_Z := nP.X - nP.Z

// Addition

add_X := n1P.X + n1P.Z

add_Z := nP.X - nP.Z

add_X *= double_Z

add_Z *= double_X

tmp := add_X - add_Z

add_X += add_Z

add_Z = tmp

add_X.square()

add_Z.square()

add_Z *= x

// Now we can do doubling

double_X.square()

double_Z.square()

// Store for later

Xn_plus_Zn_squared := double_X

double_X *= double_Z

tmp = Xn_plus_Zn_squared - double_Z

double_Z = A24 * tmp

double_Z += Xn_plus_Zn_squared

double_Z *= tmp

return (

Projective{double_X, double_Z},

Projective{add_X, add_Z}

)

}This could be optimized to reuse nP and n1P's buffers better as well

Given a point , the formula for is given by:

where:

(This formula is derived geometrically. is the slope of the tangent line to the curve at the point .)

Because features in the denominator, we can replace that with , and then calculate out the following identity:

This formula calculates given only , and can be shown to be valid in other edge cases. See: 1.

If we use projective coordinates, then we have . Plugging this into the formula we had above, we get:

In other terms, this means we have:

If we calculate this directly, a point doubling takes:

We can re-arrange things to allow more sharing:

If you note that:

The correctness of this formula becomes relatively clear.

This adjusted formula takes:

In can be shown that given and , we have:

(This is a monstrous PITA, see 1.)

In projective coordinates , we get:

This gives us the following formulas for addition:

Unlike with doubling, we need to have calculated prior. In practice, this constraint is easily accomodated.

This formula requires:

To simplify it, first note that because of the properties of projective coordinates, multiplying both and by gives us the same point:

A bit of toil gives us the following formula:

This gives us an improved:

In practice, we'll always have as , and as a small constant, giving us:

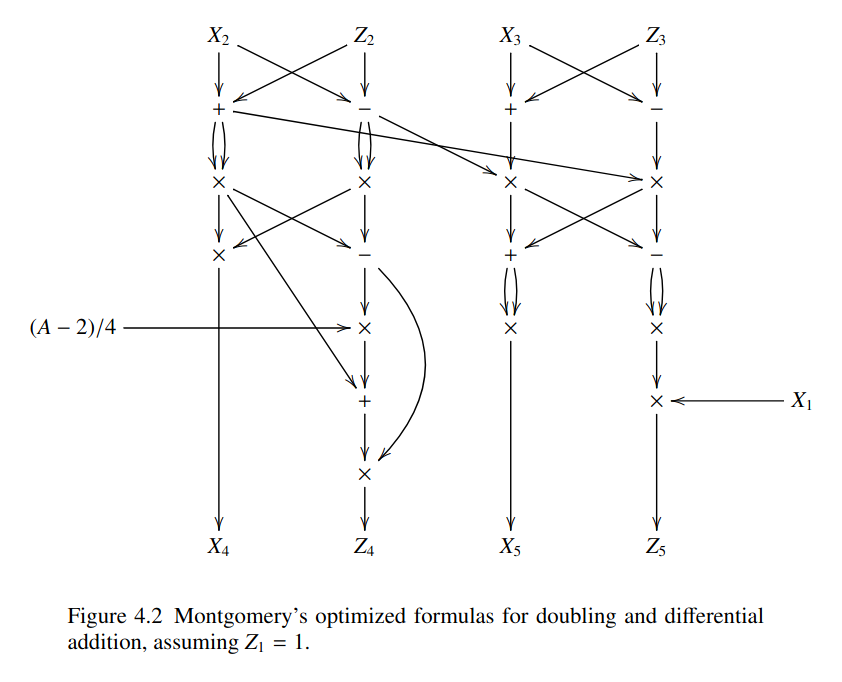

In practice, you have and , and calculate as well as together, giving you the following combined formula:

(See: 1)

One simple way to calculate is as follows. Iterate over the bits of from most to least significant. If a bit , set:

If , then set:

Our addition formula works well when we have and , and want to calculate , since the difference is , a point we already know.

At each iteration, as we rise up to , our final value, we want to keep this property, and keep the successive values around.

This, when , we do:

The first value comes from point doubling , and the second from differential point addition, using the fact that the difference is .

When , we want to do:

We can calculate the first value through point addition, and the second through point doubling.

In fact, if we define these two functions as , and respectively, we notice that comes from swapping the input, and then the output. With:

We have:

Thus, an algorithm for doing our ladder would be:

for b in bits:

if b == 1:

swap(P, Q)

(P, Q) = step0(P, Q)

if b == 1:

swap(P, Q)

return PWe can make this "constant-time", by replacing our branching with a conditional swap:

for b in bits:

cswap(b, P, Q)

(P, Q) = step0(P, Q)

cswap(b, P, Q)

return PIf we have two conditional swaps chained together

cswap(bits[i], P, Q)

cswap(bits[i - 1], P, Q)Which happens between iterations, notice that this is effectively:

cswap(bits[i] ^ bits[i - 1], P, Q)because of this, we can effectively do:

cswap(bits[N - 1], P, Q)

step0(P, Q)

cswap(bits[N - 1] ^ bits[N - 1], P, Q)

step0(P, Q)

...

cswap(bits[1] ^ bits[0], P, Q)

step0(P, Q)

cswap(bits[0], P, Q)Noting that 0 ^ bits[N - 1] = bits[N - 1], we can effectively do:

swap := 0

for b in bits:

swap ^= b

cswap(swap, P, Q)

swap = b

step0(P, Q)

cswap(swap, P, Q)

return PThis allows us to efficiently compute whether or not we need to swap.

This is the gist of things, see the summary up top for more useable pseudo-code.