A Sketch of Synthetic Cryptography

This is a brief post sketching out a synthetic style of cryptography. In this style, one doesn’t appeal to any kind of complexity theory, probability, or even adversary.

Instead, one has rules for considering two “games” to be equal, and applies these at a very granular level. Of course, one can interpret these rules in a concrete model. All of the examples in this post should work in the standard asymptotic model. In fact, I’ve tried to structure things so that concrete bounds are easily derivable, if you care about that kind of thing.

This post is a very brief tour of the important topics one might cover in a course on cryptography. Namely, we see:

- dealing with randomness and guessing in this framework,

- symmetric encryption security,

- pseudo-random functions,

- properties of random functions,

- public key encryption,

- the KEM-DEM paradigm for public key encryption,

- constructing a CPA secure KEM from groups, in the random oracle model.

Hopefully this tasting platter gives you a good idea of what proofs in this style can look like.

String Diagrams

To start, we’ll first go over the general rules for manipulating diagrams representing cryptographic games. This presentation tries to be intuitive rather than overly formal, so the precise definition or rules are less important than developing a “feel” for how to play with the diagrams. We leave a formal presentation of string diagrams in general to other resources, such as [PZ23].

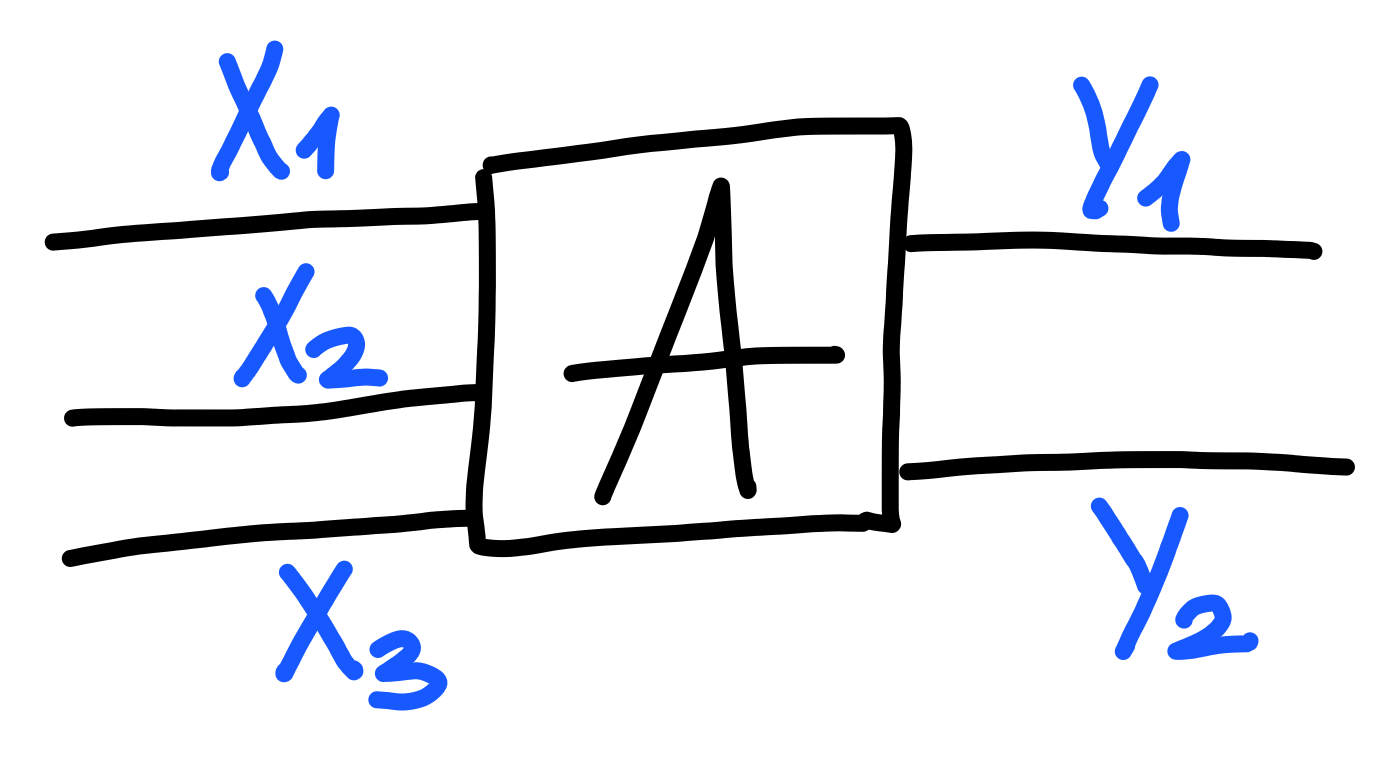

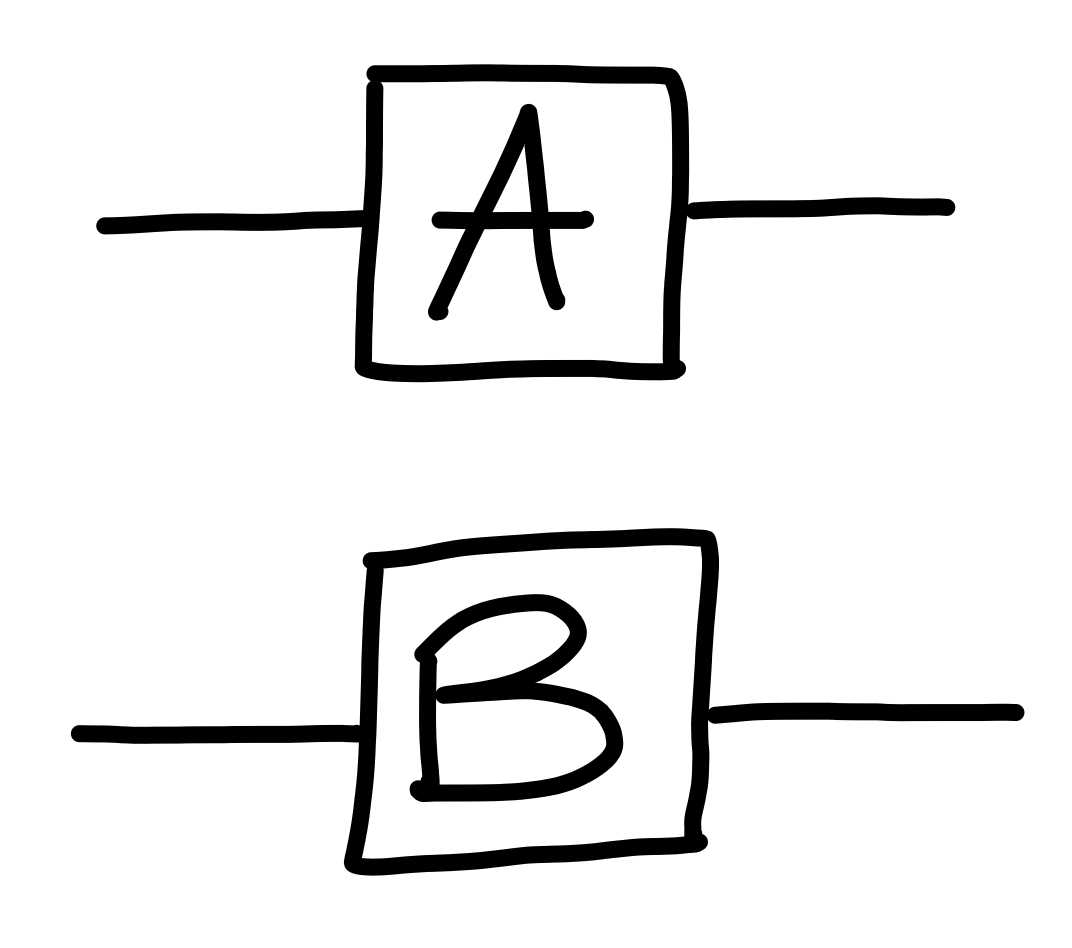

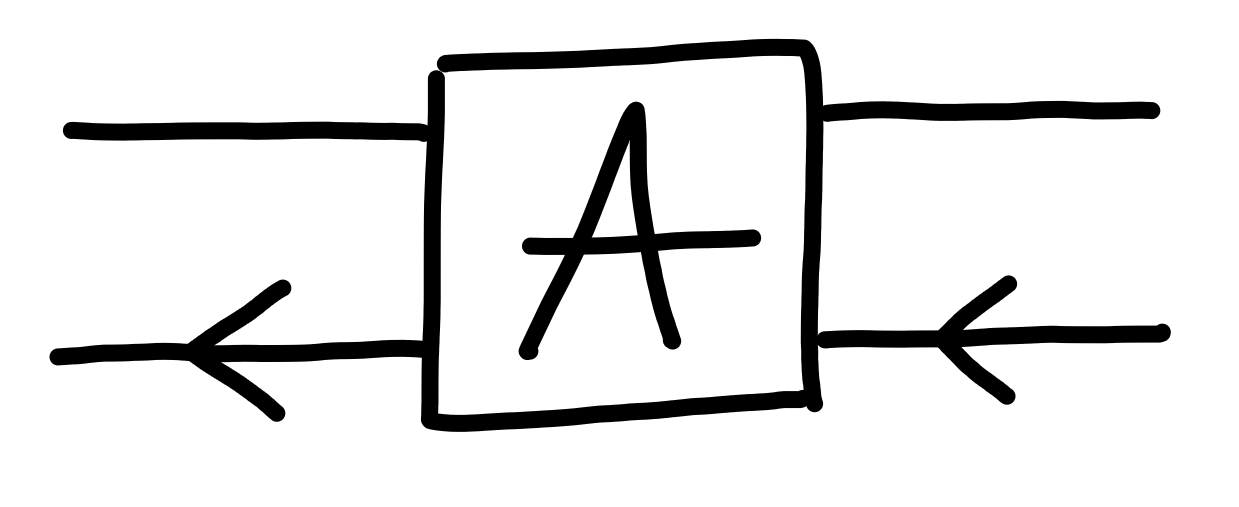

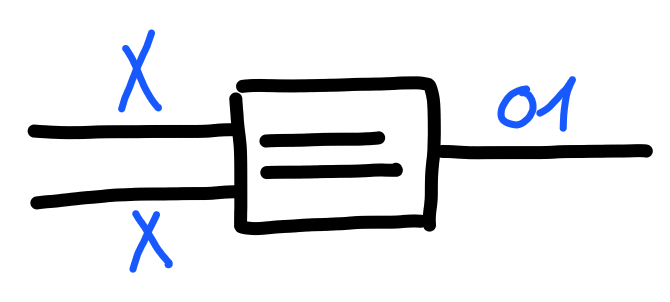

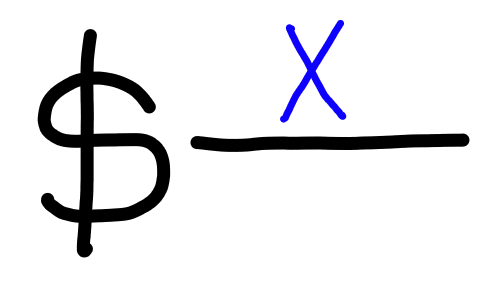

Our starting point will be a “process”:

In other frameworks, one might call this a cryptographic game, or a package. Because our level of granularity is very fine, we simply refer to it as a process instead. A process is connected to several input wires, on the left, and several output wires, on the right. Each of these wires has a type, giving the process as a whole a signature, which we’d write in this case as: $$ A : X_1 \otimes X_2 \otimes X_3 \to Y_1 \otimes Y_2 $$ As this notation might suggest, we can think of a process as a kind of function, taking in some inputs, and producing some outputs.

Some important differences between a process and a function are:

- A process is randomized.

- A process may not use all of its inputs.

- A process may produce some outputs before others.

The last two points are actually quite important. Another way to think of them is that wires connected to a process are either “dead”, carrying a dummy value $\bot$ indicating this, or “alive”, then carrying a value of the type that wire is. A wire can change its value from dead to alive, but once it is alive, it will never change its value again.

Each output wire has a set of input wires it depends on, and as soon as all of these wires are alive, the process will produce an output on this wire in particular, in a randomized way. Any given output wire may have their value ready before other output wires.

If this doesn’t make complete sense in the abstract, that’s fine, we’ll be highlighting how this point shows up as necessary.

In the next subsections, we look at various rules for gluing processes together, and manipulating diagrams of connected processes.

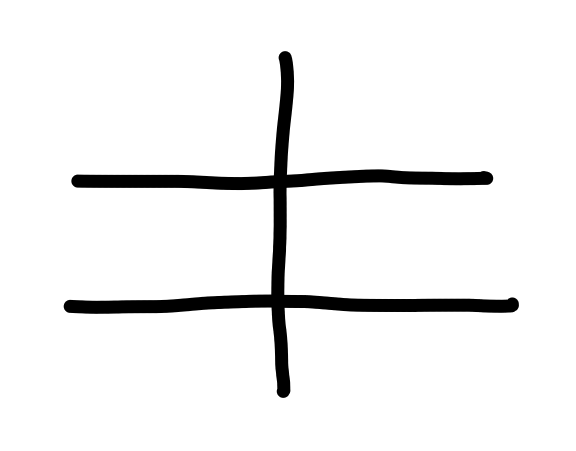

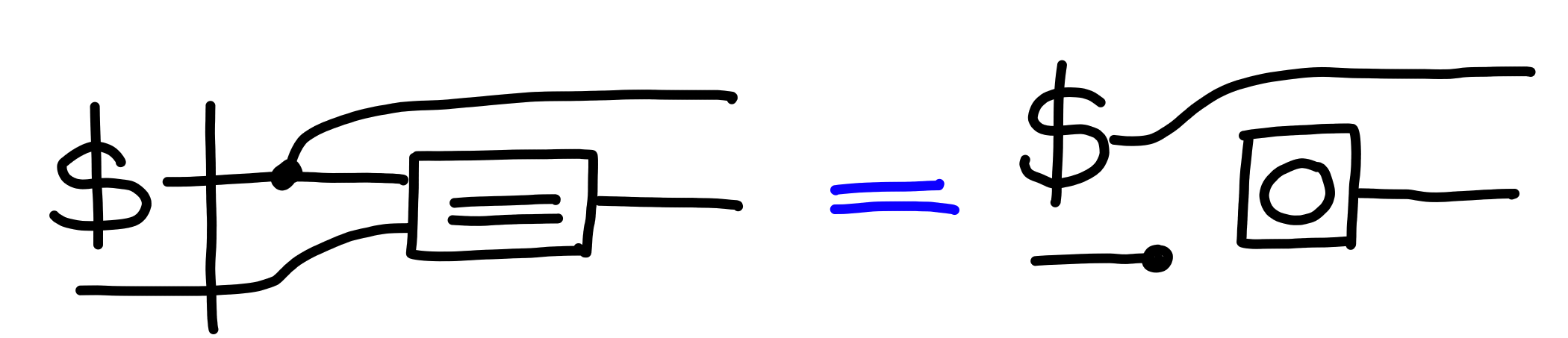

Shorthand for Products

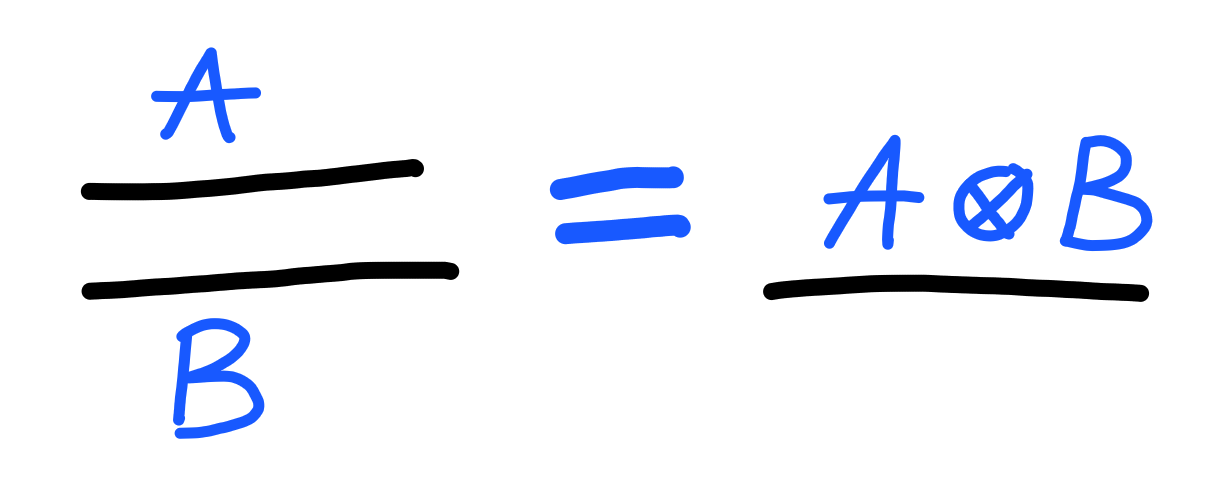

The type $A \otimes B$ denotes the type of “both $A$ and $B$”.

Because of this, we can treat two wires as one, like this:

Sometimes processes will consume the wires split, and other times,

some processes will be written with the wires joined.

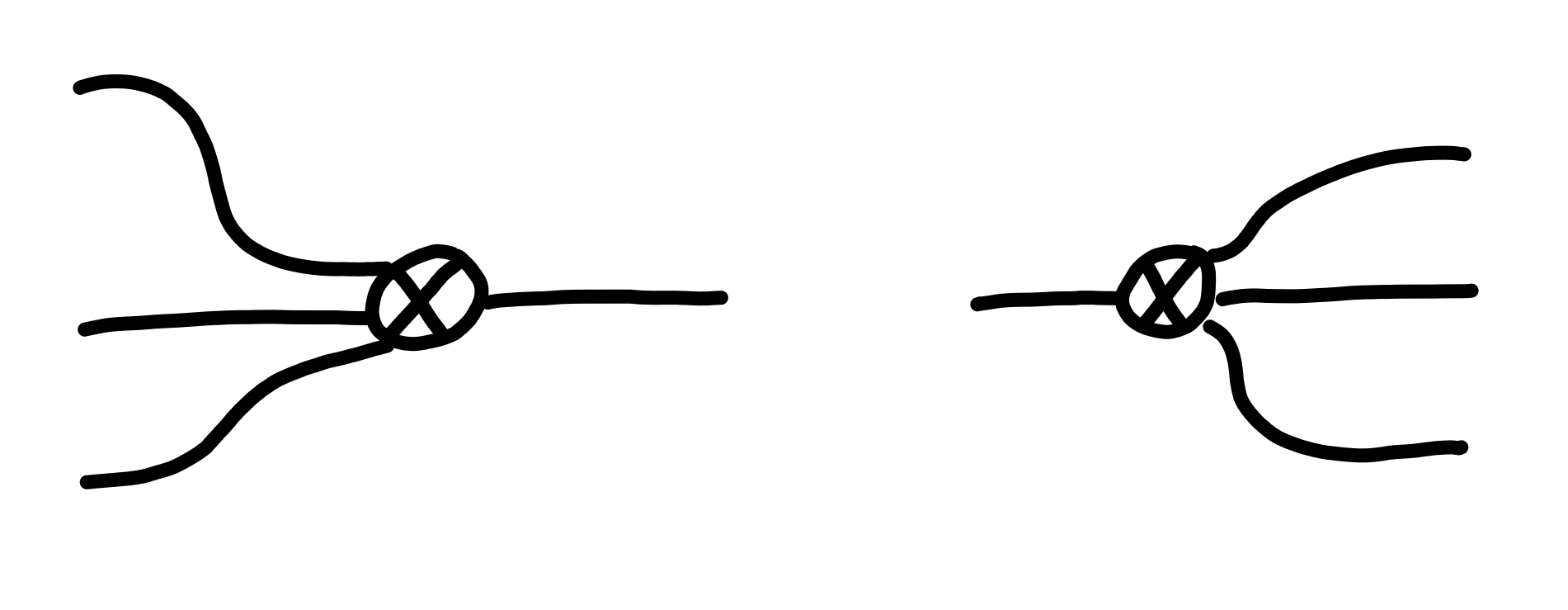

To convert between the two, we use the following bits of notation:

As a shorthand, we also write $A^n$ to denote $A \otimes A \otimes \ldots \otimes A$, $n$ times.

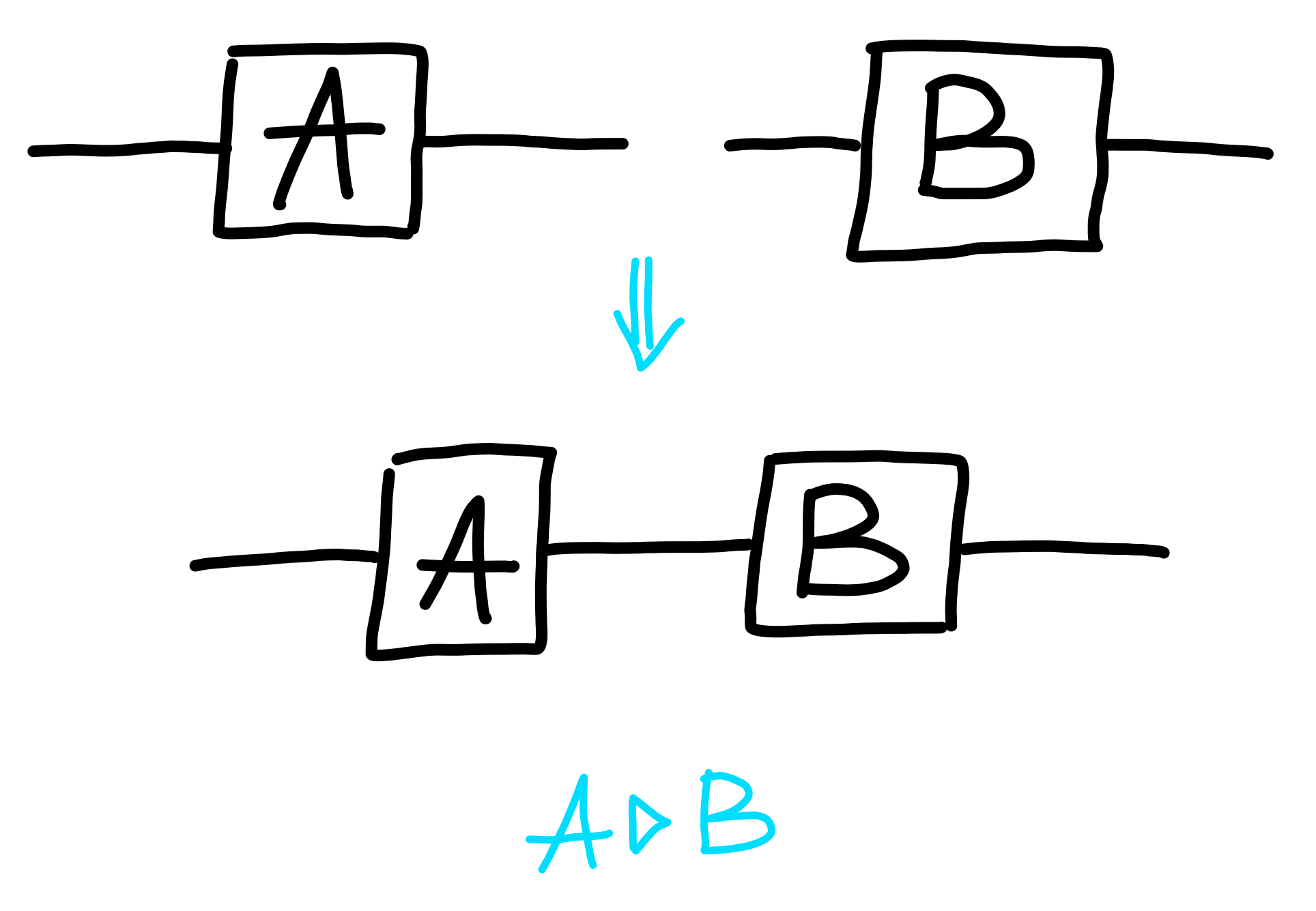

Back-to-Back

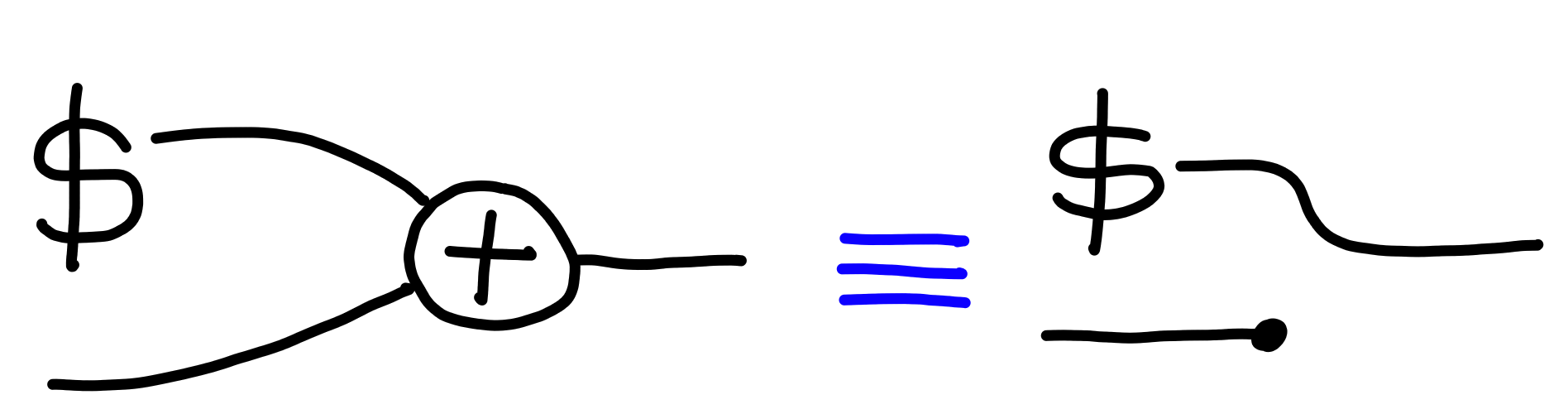

The first way to connect two processes is via their wires:

In terms of the underlying math, given processes $A : X \to Y$, and $B : Y \to Z$, we can define the process: $$ A \rhd B : X \to Z $$

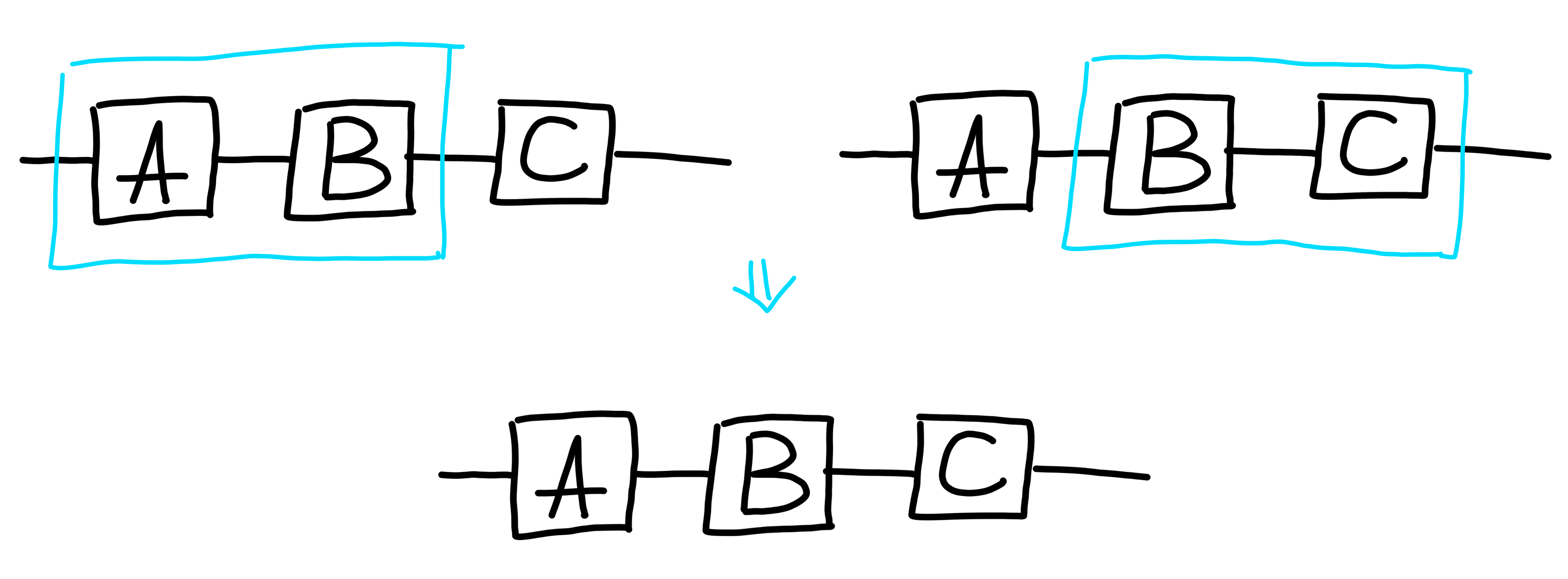

One crucial aspect of composition is that the order in which we compose doesn’t matter:

This is also suggested by the notation we use. With our notation, it’s not easy to distinguish between the two orders of composing, which is fine, since the order doesn’t matter! This is the first in an instance of many notational choices in our diagram system which reflect equivalences in the underlying processes.

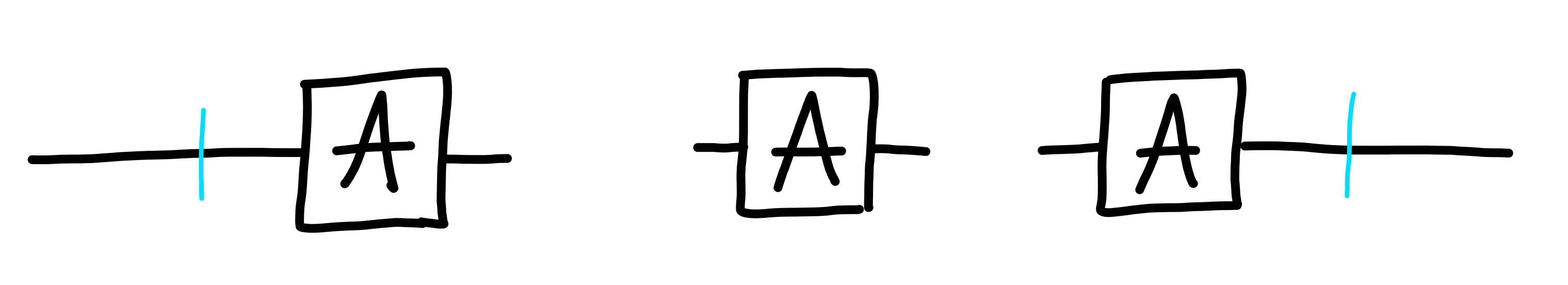

Side-by-Side

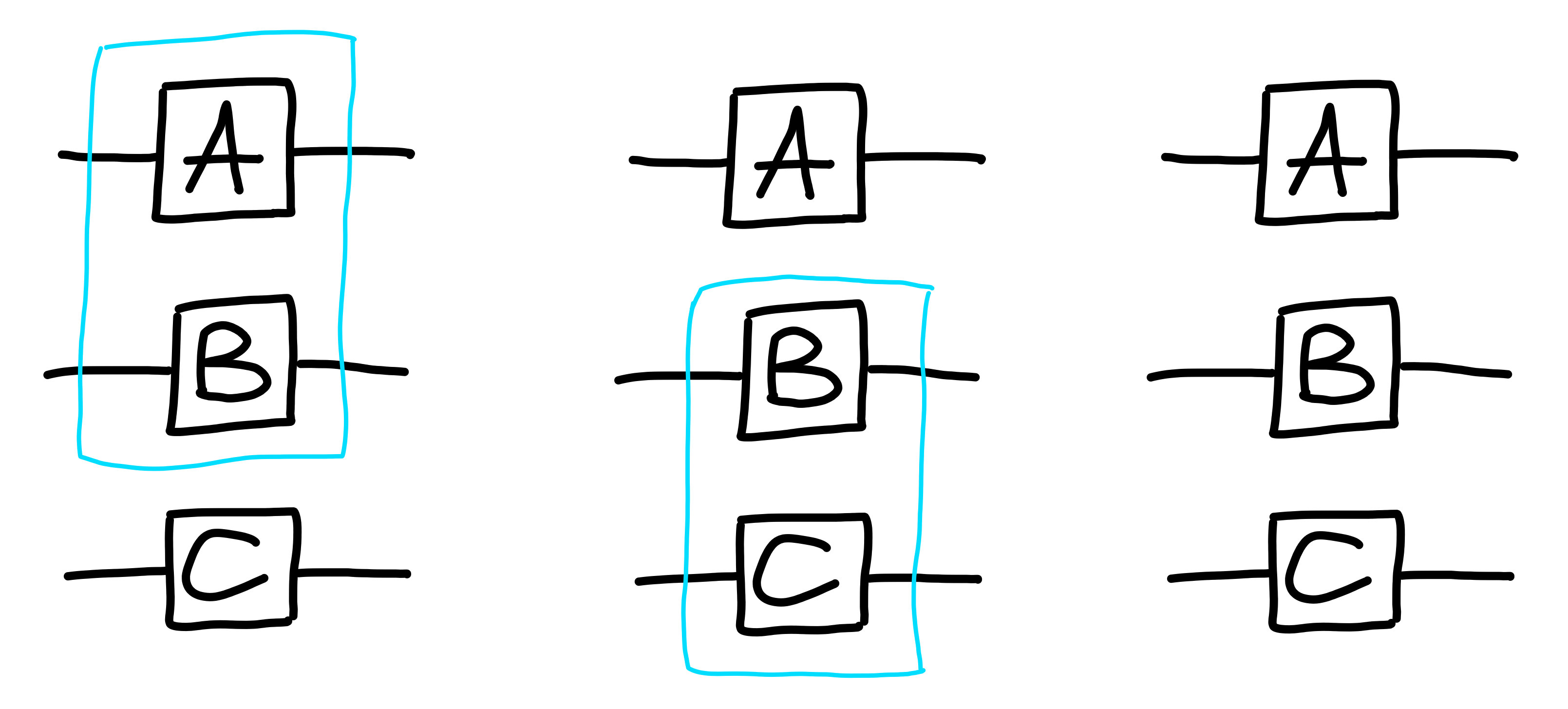

The other way to compose protocols is via tensoring, or, side-by-side:

It’s important to note that the point about output wires being able to have values independently of each-other is important. The output on $A$’s section of the combined process will be ready as soon as the input on $A$ is, and ditto for $B$. Each half doesn’t need to “wait” for the other half to be ready.

As with composition, the order in which we tensor doesn’t matter, as the notation suggests:

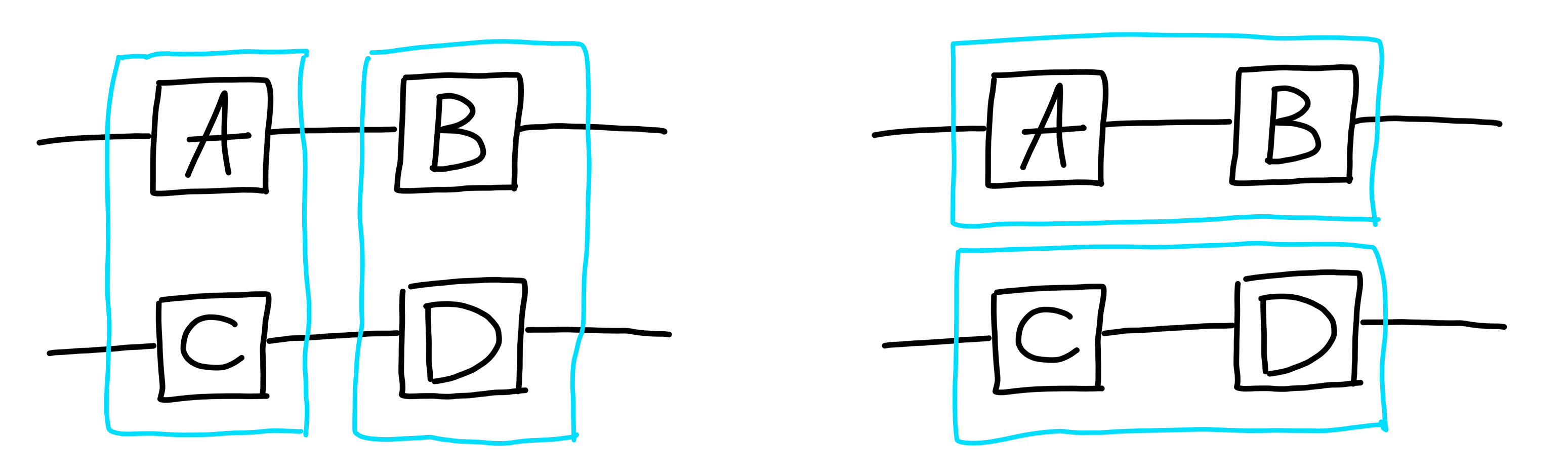

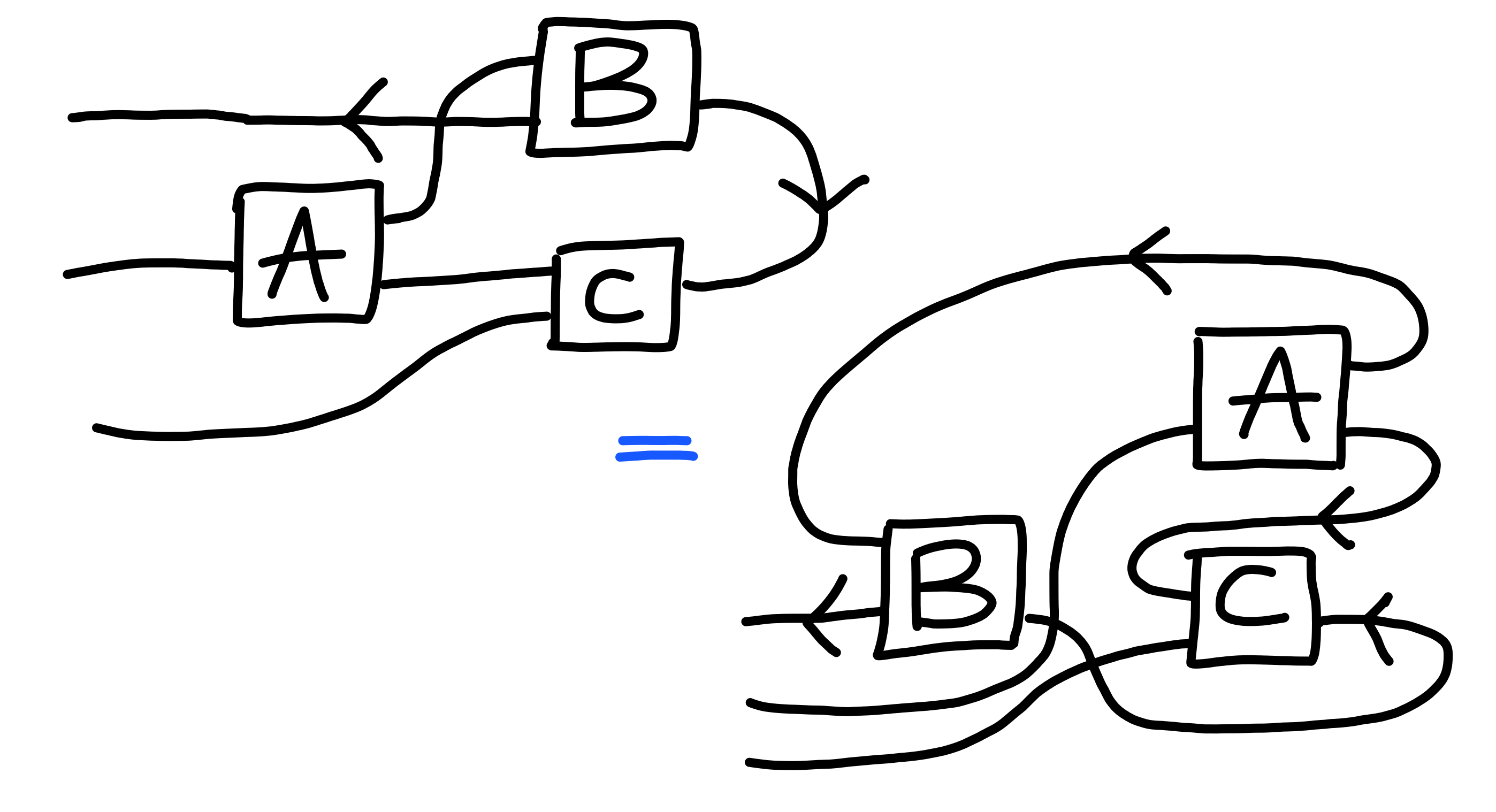

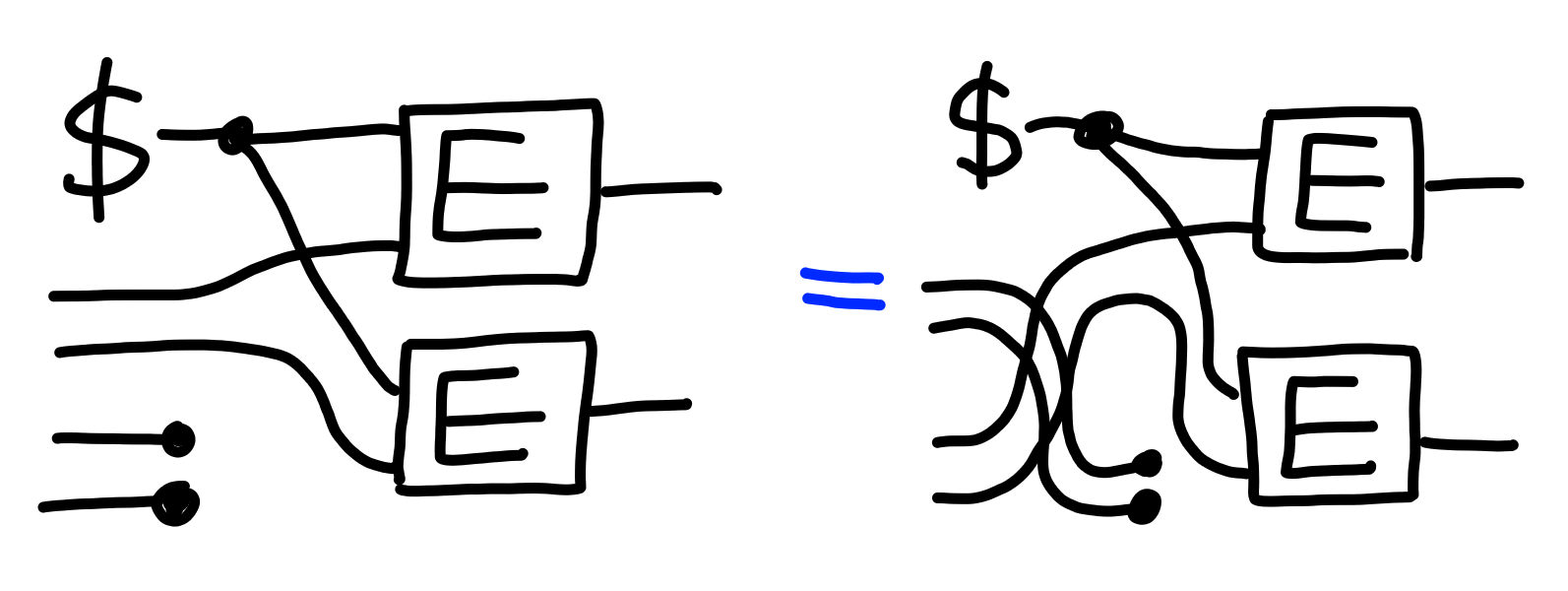

Interchange

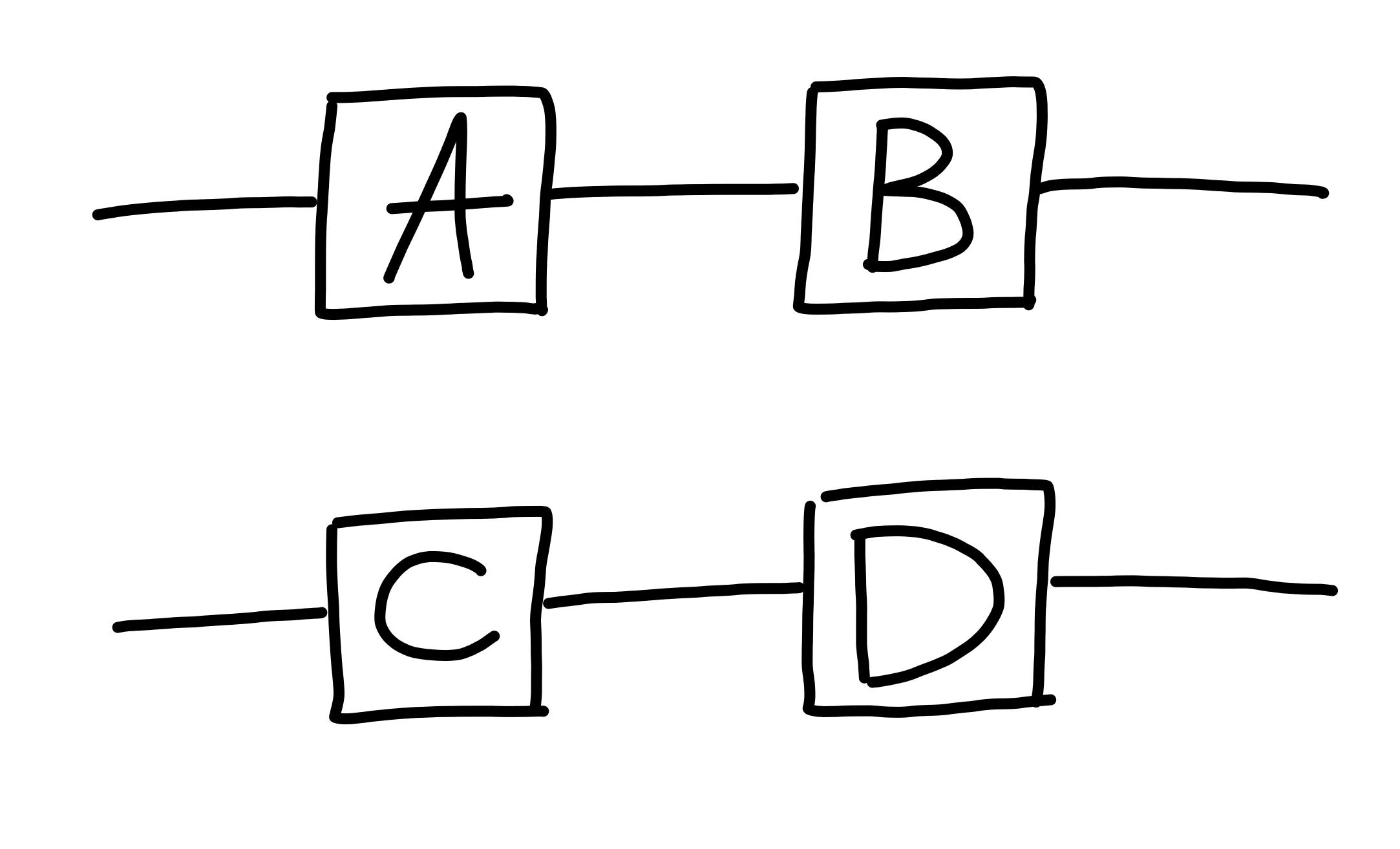

Composition and tensoring also play very nicely with eachother.

If you have processes $A, B, C, D$, boxed up like this:

The order you do these operations does not matter! Once again, the notation expresses this fact by not reflecting any differences in terms of the diagram.

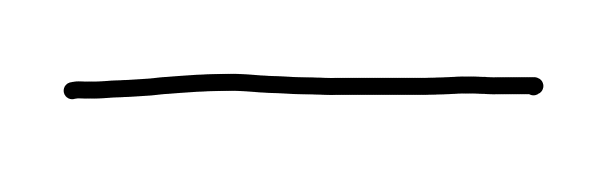

Sliding

Next, we introduce little gadgets we can use.

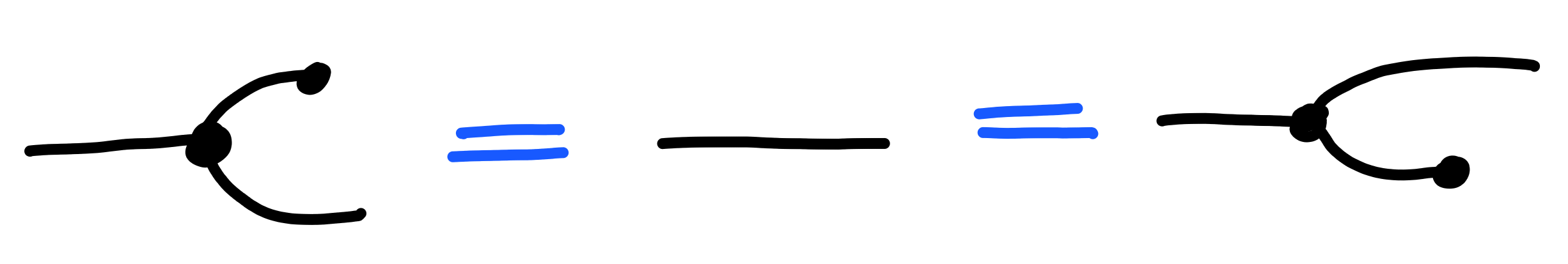

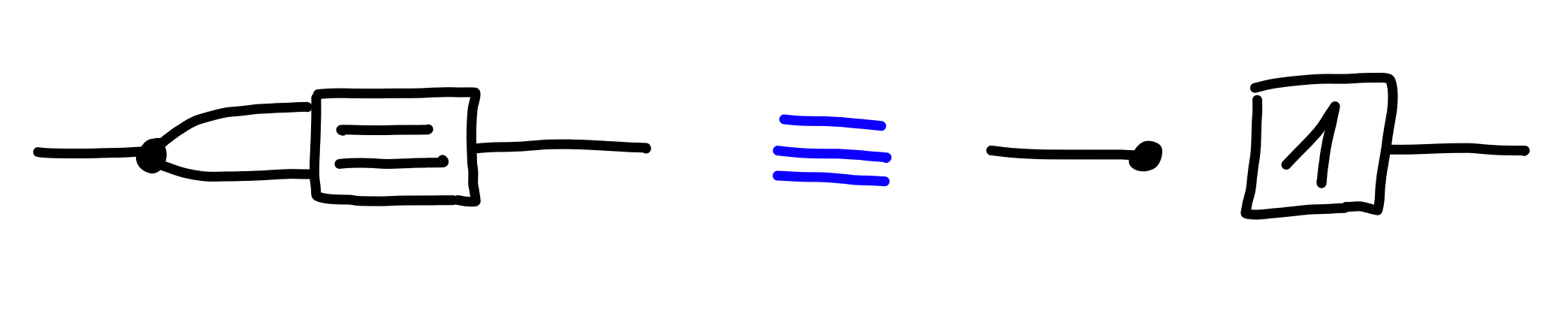

The first of these gadgets is “$1$”, a process

which simply returns its input:

The defining property is that $1$ composed with any other process,

in front, or in back, is just the same process:

Combining this property with that of interchange allows us to “slide” processes along wires:

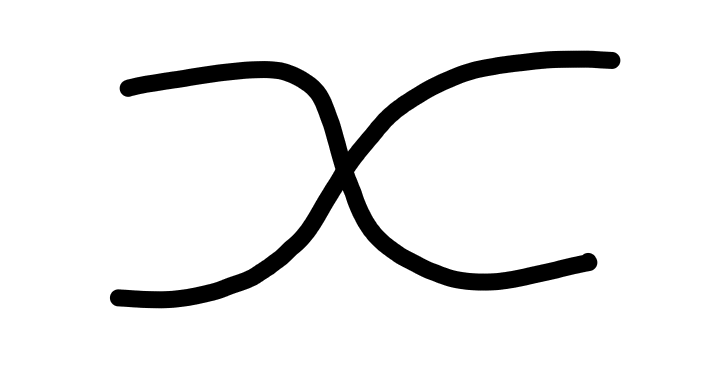

Swapping

Next, we introduce another gadget, which is a process which

swaps its inputs:

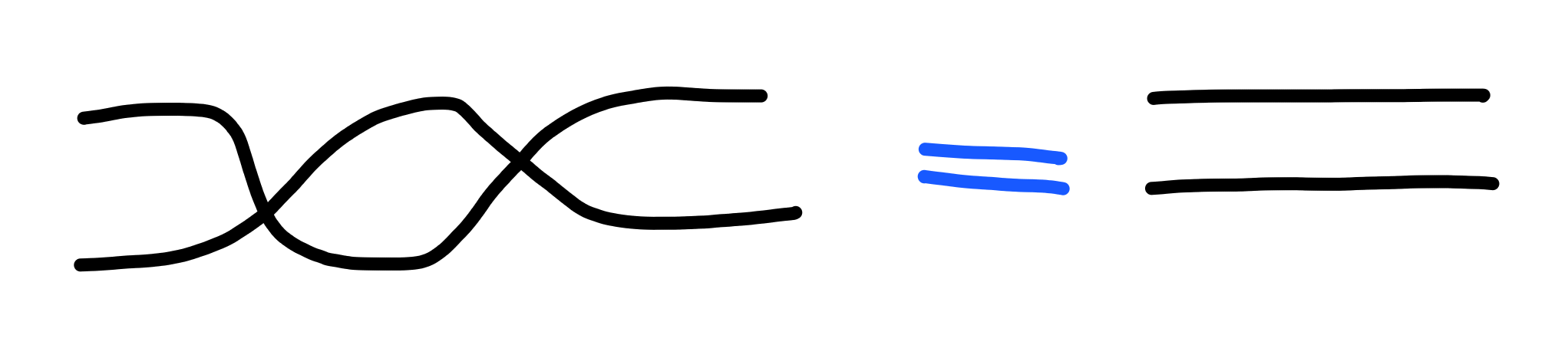

One key property of swapping is that doing it twice is the same

as not swapping:

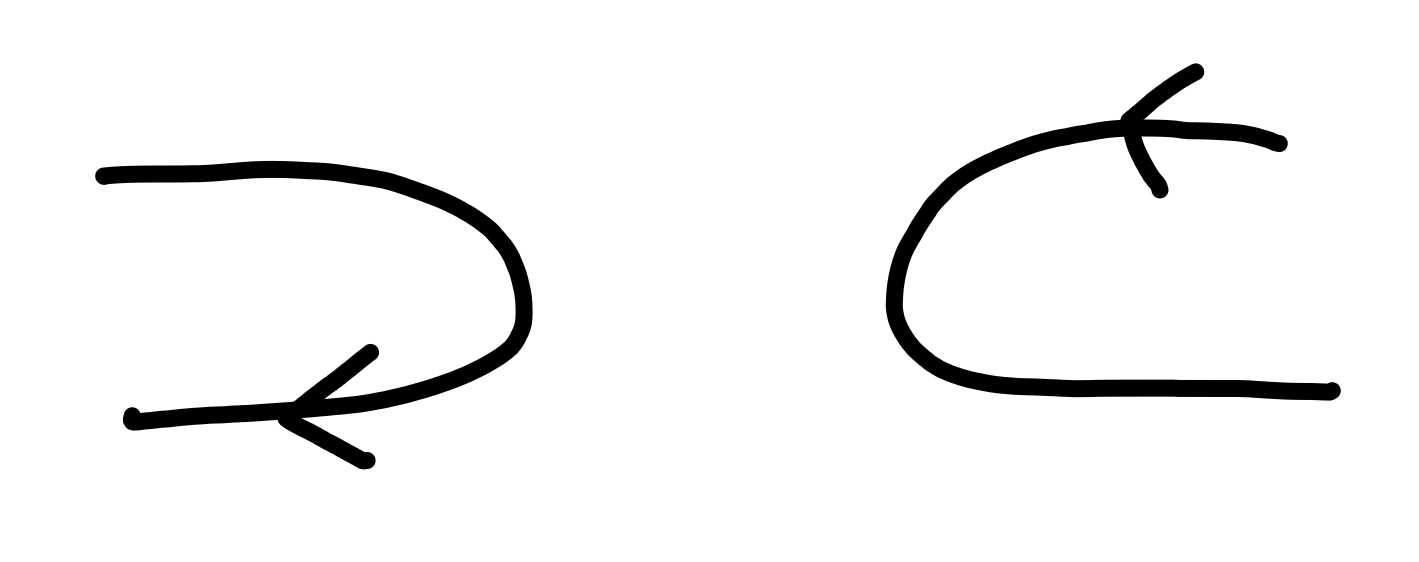

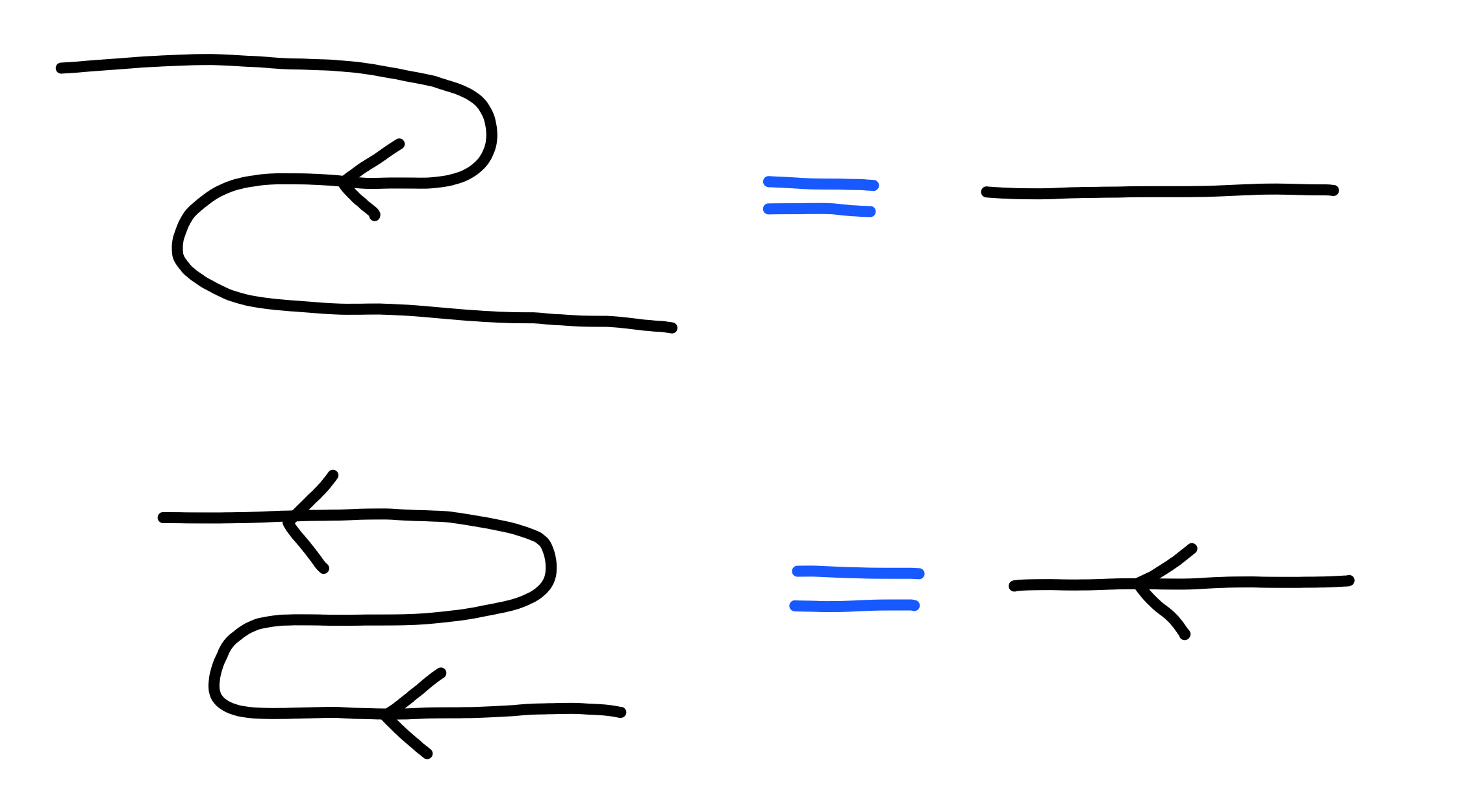

Backwards and Forwards

Next, we also consider processes which may also have inputs

on the right, and outputs on the left:

There are two fundamental gadgets which reverse the flow of arrows:

As one might expect, these gadgets satisfy a natural law:

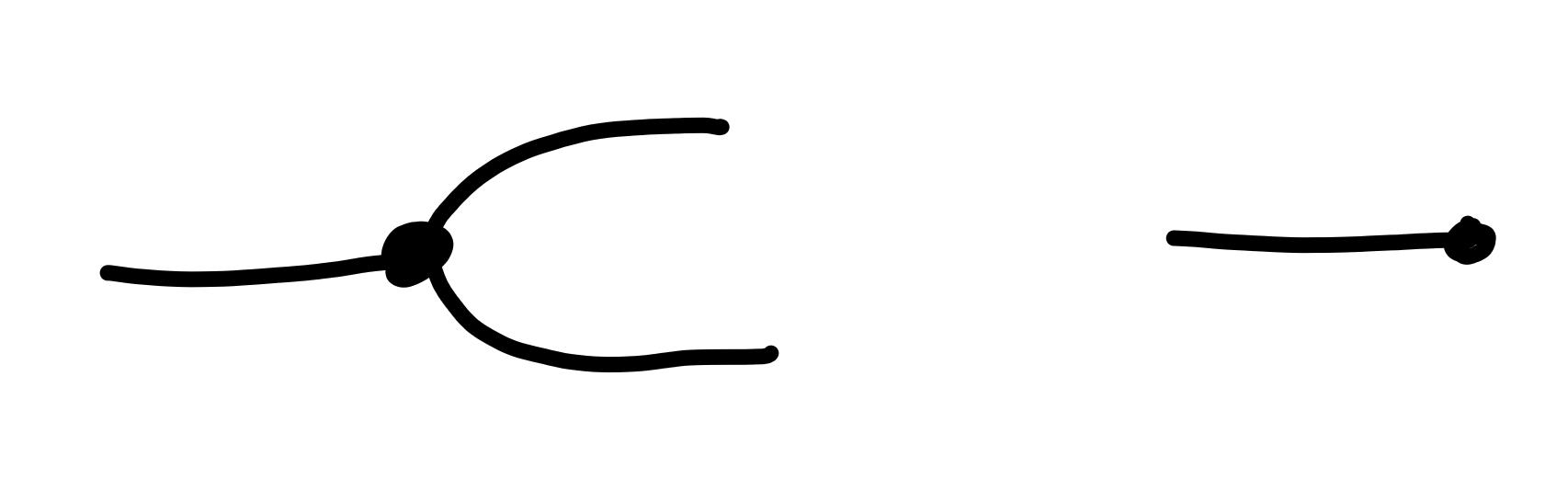

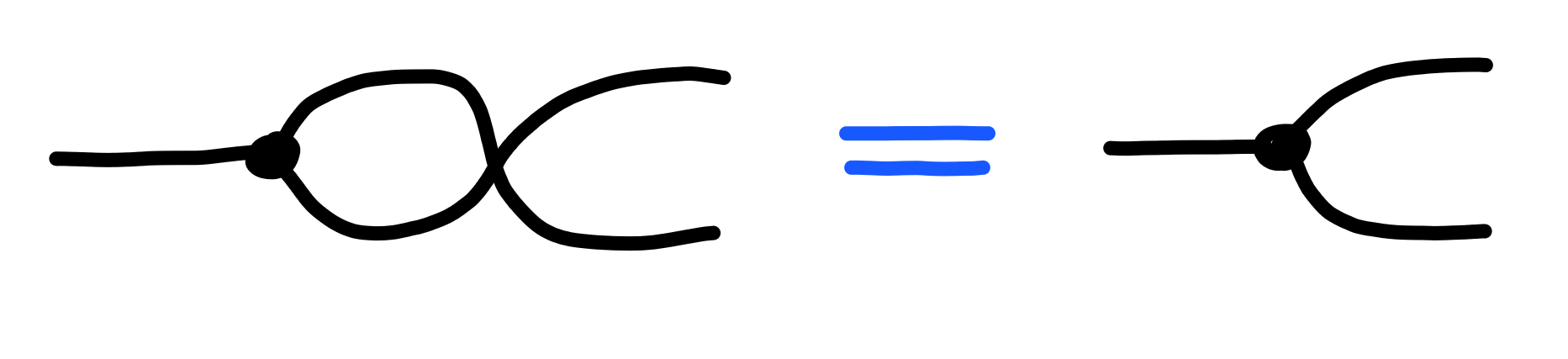

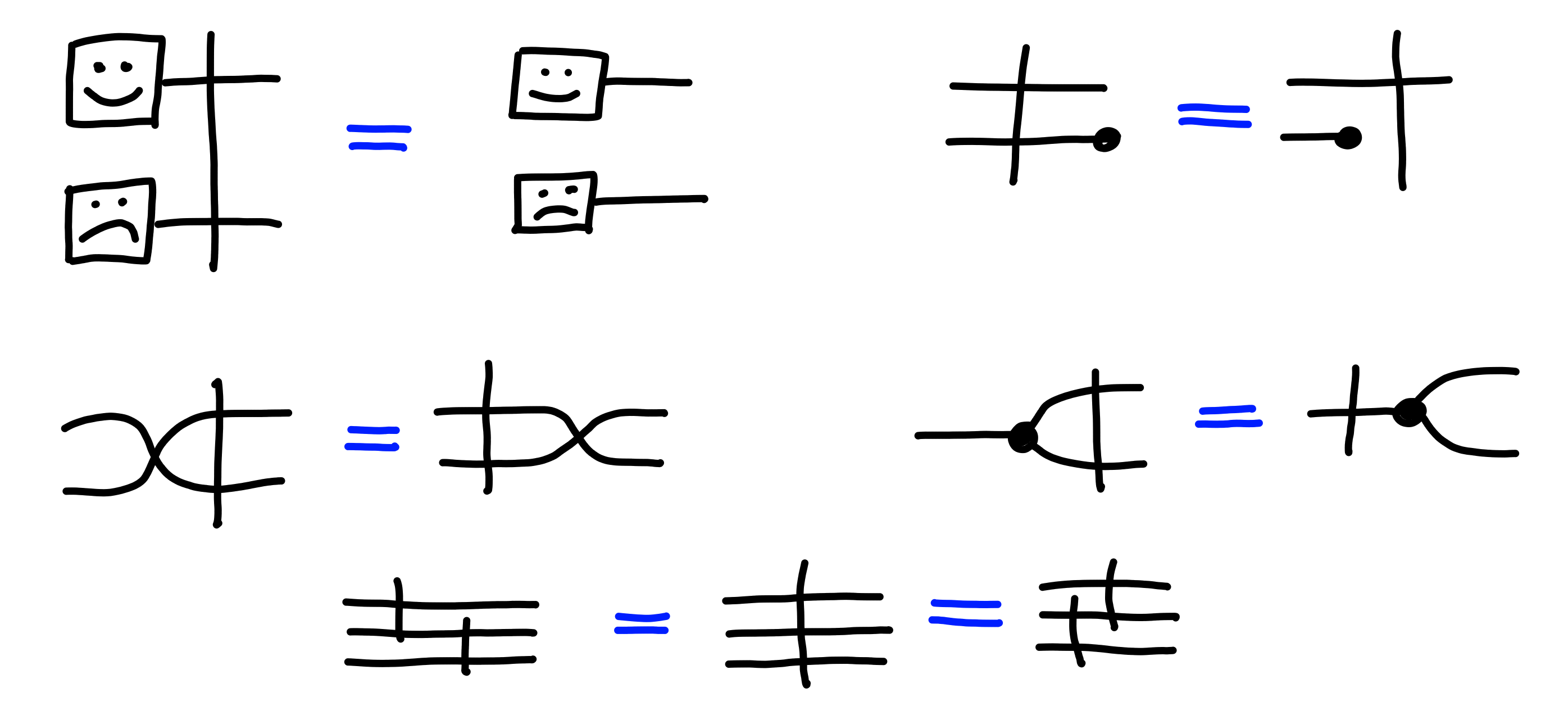

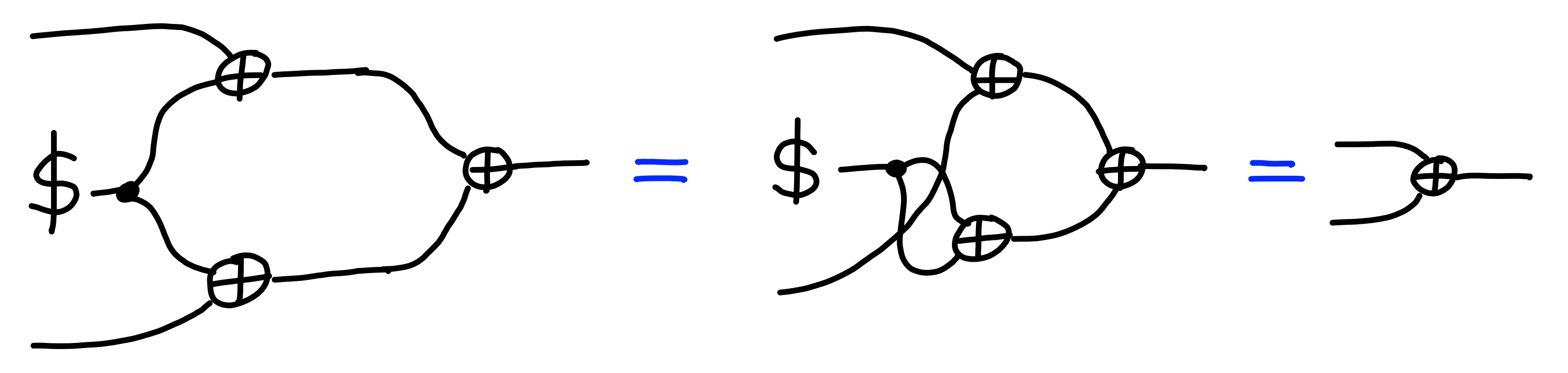

Copying and Deleting

The final gadgets we’ll look at our processes which copy and discard information:

We can think of the first process as copying its input, and outputting it on two wires, and the second process as ignoring its input, producing no output.

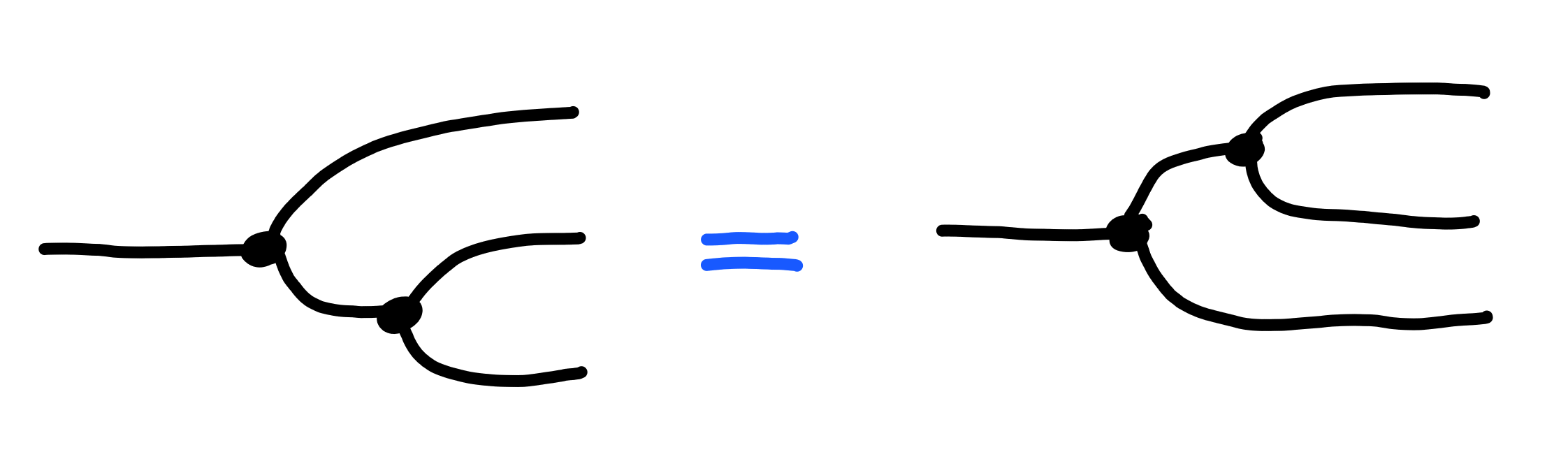

These satisfy a few properties.

First, when we copy twice to get three outputs,

the order we do this in does not matter:

Summary

To summarize, processes are boxes, with inputs and outputs, representing a randomized machine which can write values, once, to its output wires, by reacting to inputs provides on its input wires.

Inputs and outputs can appear on other side, and we can move boxes around freely, as long as the connections between inputs and outputs are preserved.

As an example of this kind of easy manipulation, the following

two diagrams represent the same process:

The notation we’ve chosen is such that it reflects this kind of equality very easily, freeing us to not really have to think all that much about these low level details.

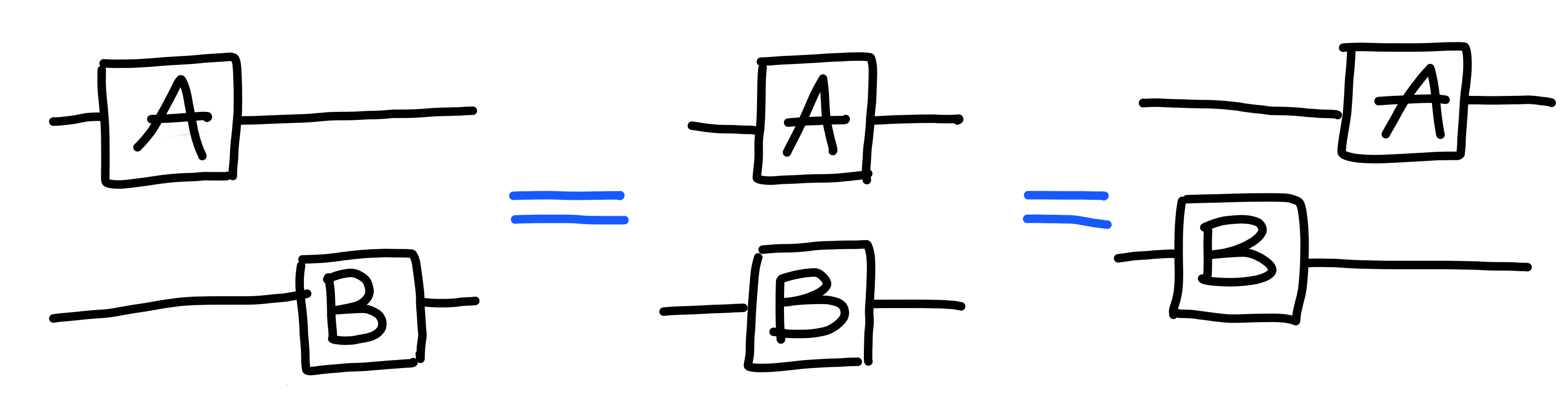

Properties and Rewrites

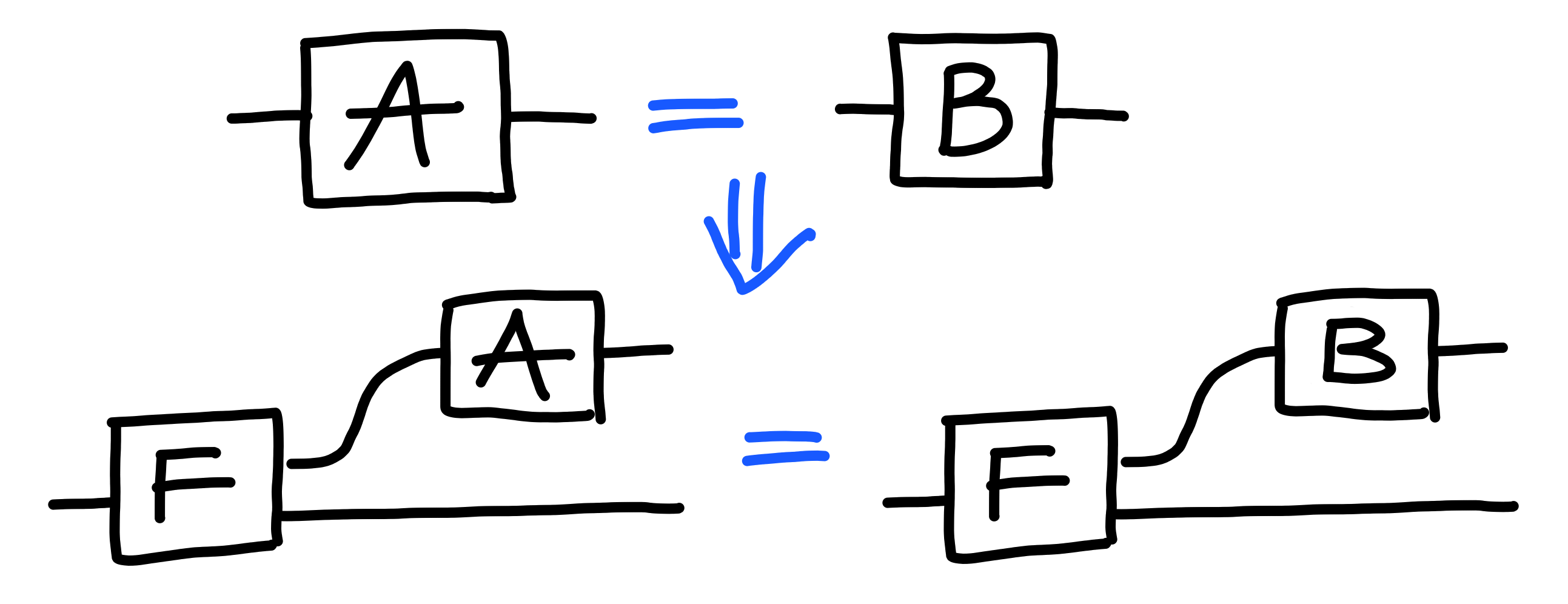

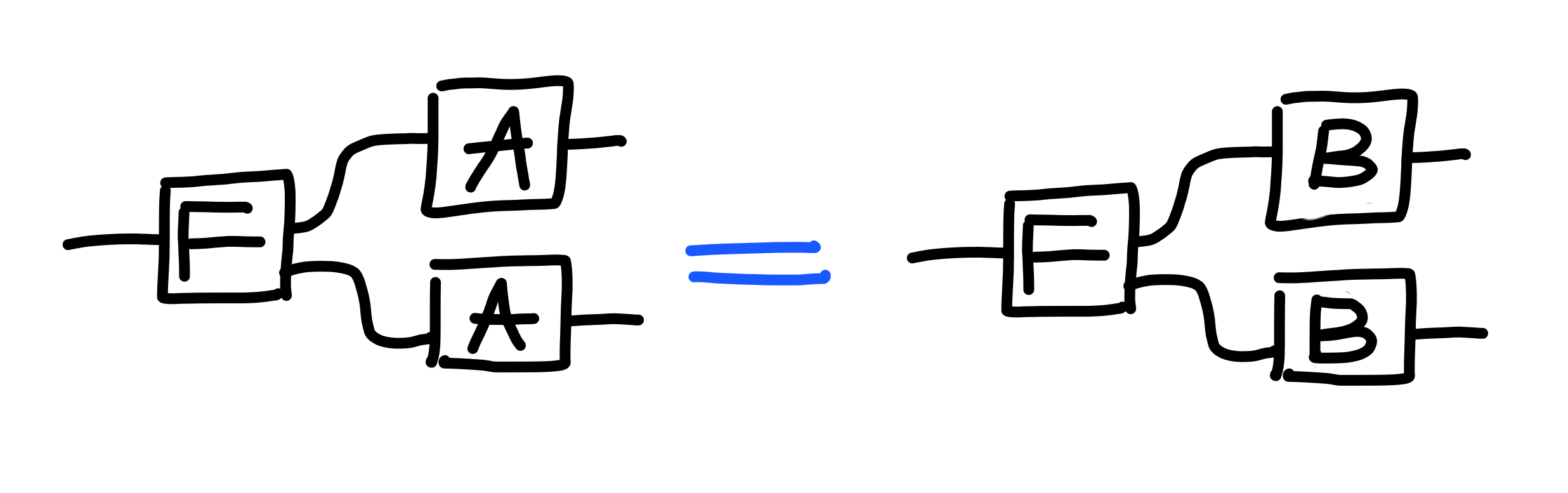

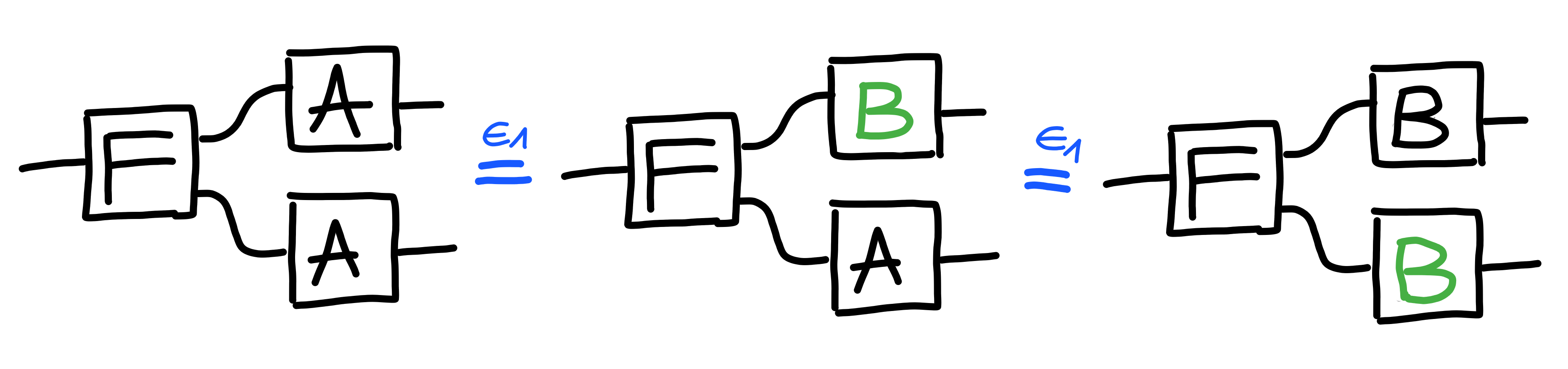

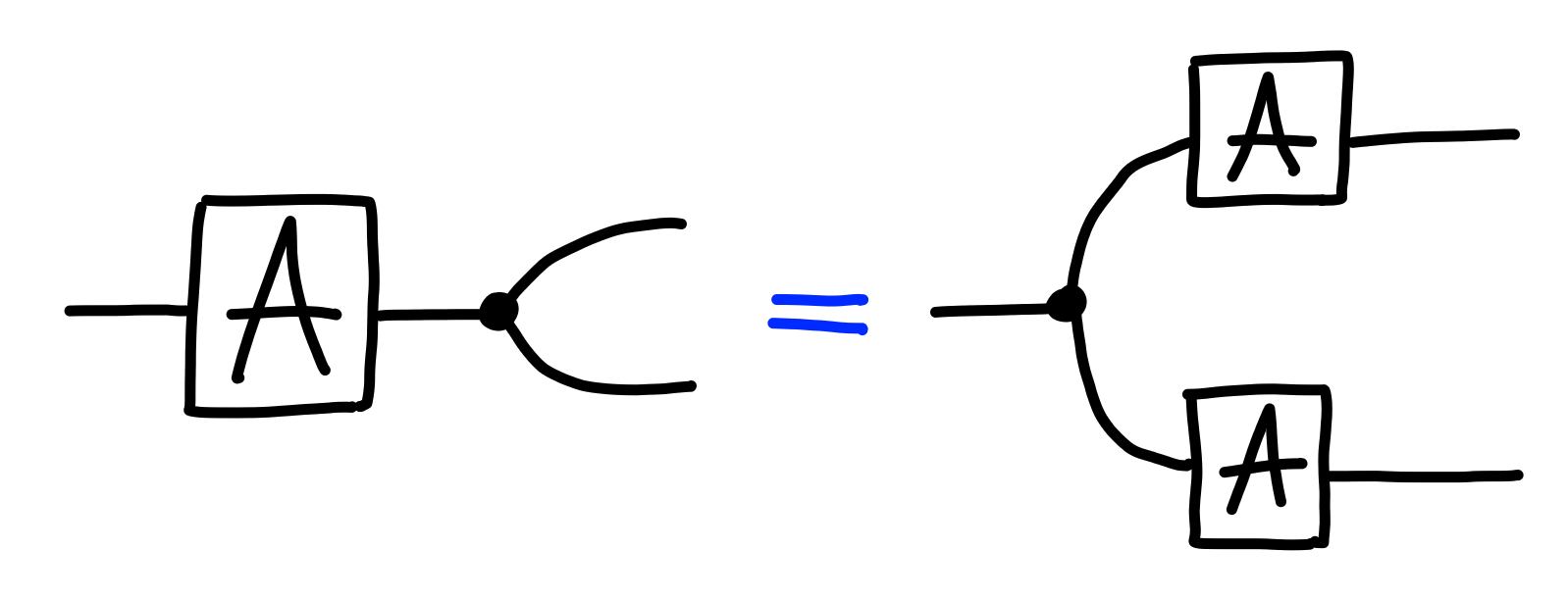

One crucial aspect of the calculus we’re developing is that if

a process is equal to another in isolation,

then it will also allow us to substitute that process

for the other in an arbitrary context:

In cryptography, often times we have rules that we want to play around with, but that we don’t assume to be absolutely true. Rather, we care about what rules can be deduced from other rules. For example, if some problem (e.g. RSA) is hard, then we can build secure public key encryption.

In these deductions, we also care how many times we use a given assumption. This allows us to work backwards, and figure out what parameters we need to use in the assumptions to get enough security in the deductions.

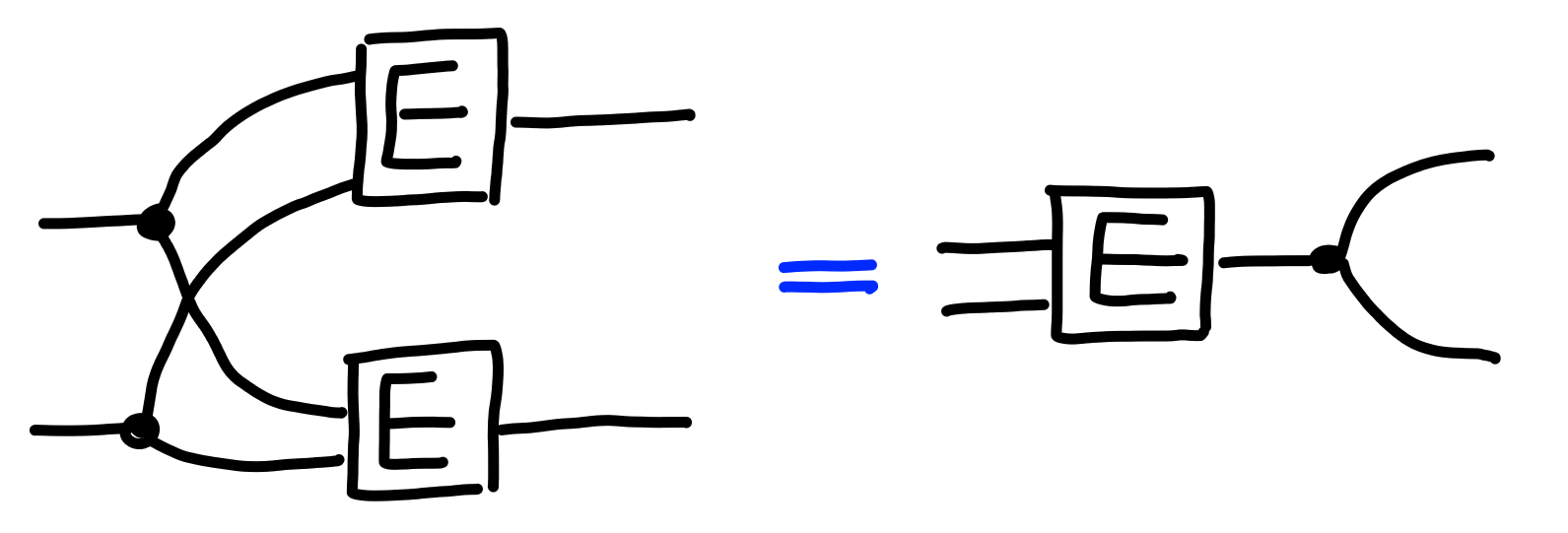

So, to do so, we define the notion of a “property”, which is just a named rule.

As an example, consider the following property,

$\Pi[\text{AB}]$:

We also have deductions, which are of the form: $$ \Pi_1 \times \Pi_2 \times \ldots \multimap \Pi $$ The rule is that each assumed property on the left can only be used a single time in the deduction. As a shorthand, we write $\Pi^n := \Pi \times \ldots \times \Pi$, $n$ times.

As an example deduction,

consider $\Pi[\text{Example}]$, defined via:

The following deduction holds:

$$

\Pi[\text{AB}]^2 \multimap \Pi[\text{Example}]

$$

As demonstrated by the following proof:

Booleans

Now, we move from a very abstract context, and towards actual concrete types that exist in cryptography.

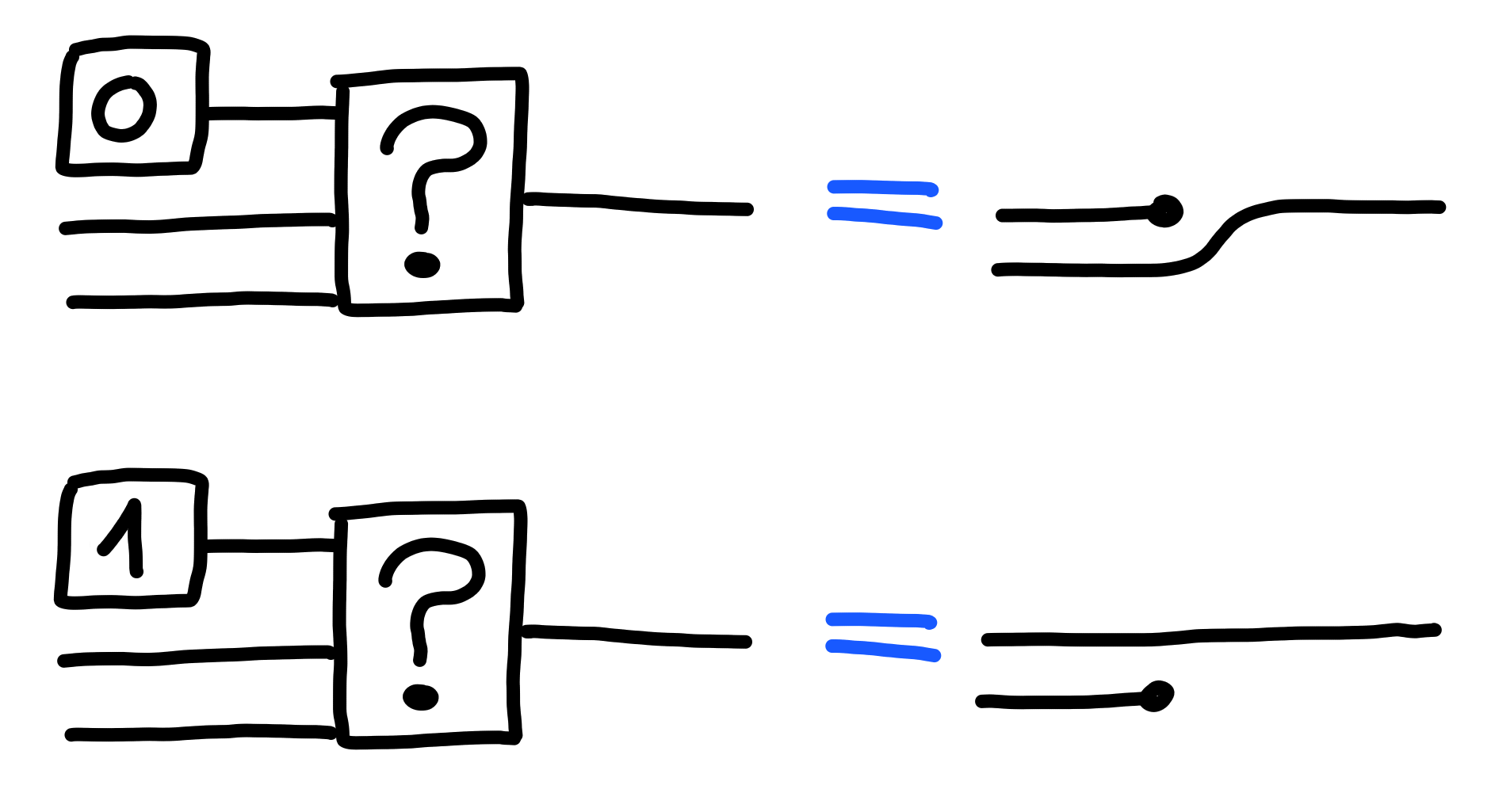

The first such type we look at is that of booleans, or the set $\{0, 1\}$, also written $\texttt{01}$ for convenience.

We define booleans via their effect on a selector function “$?$":

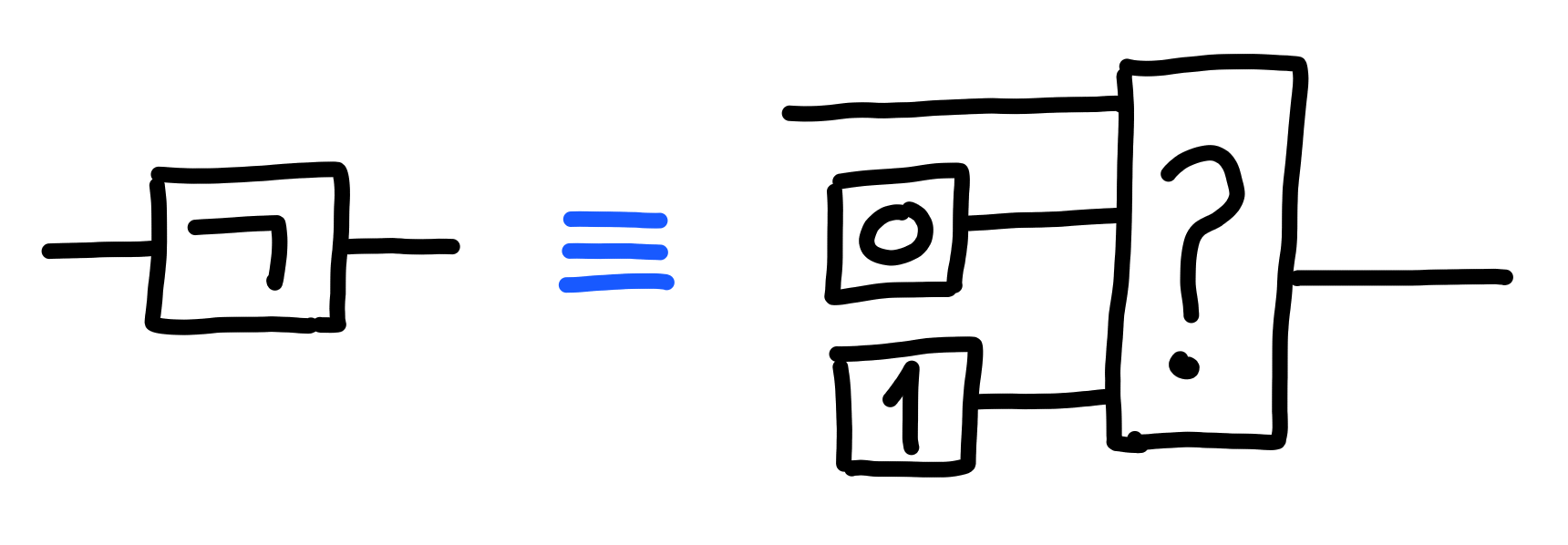

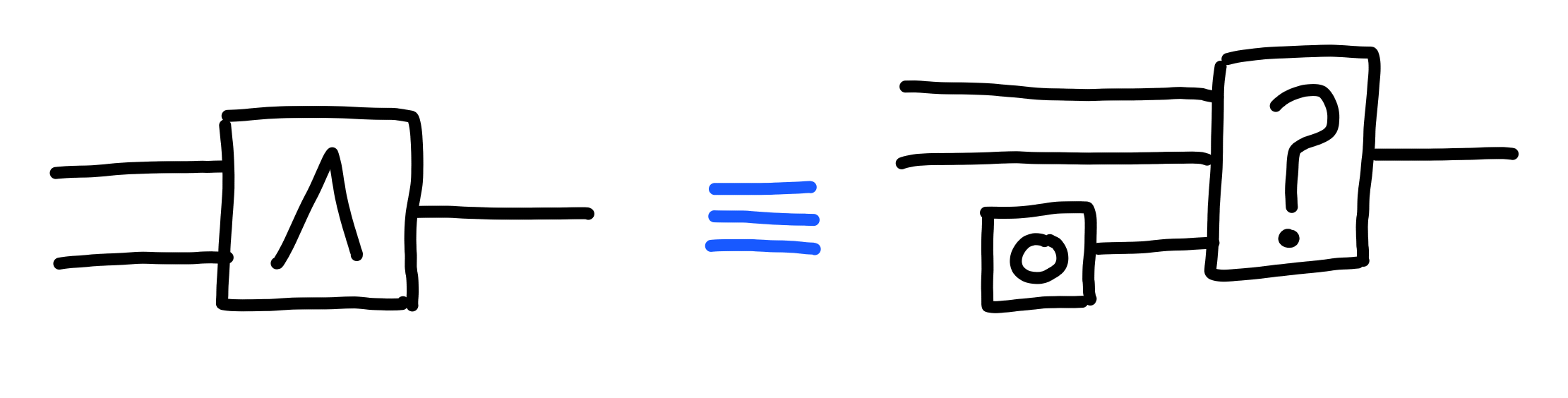

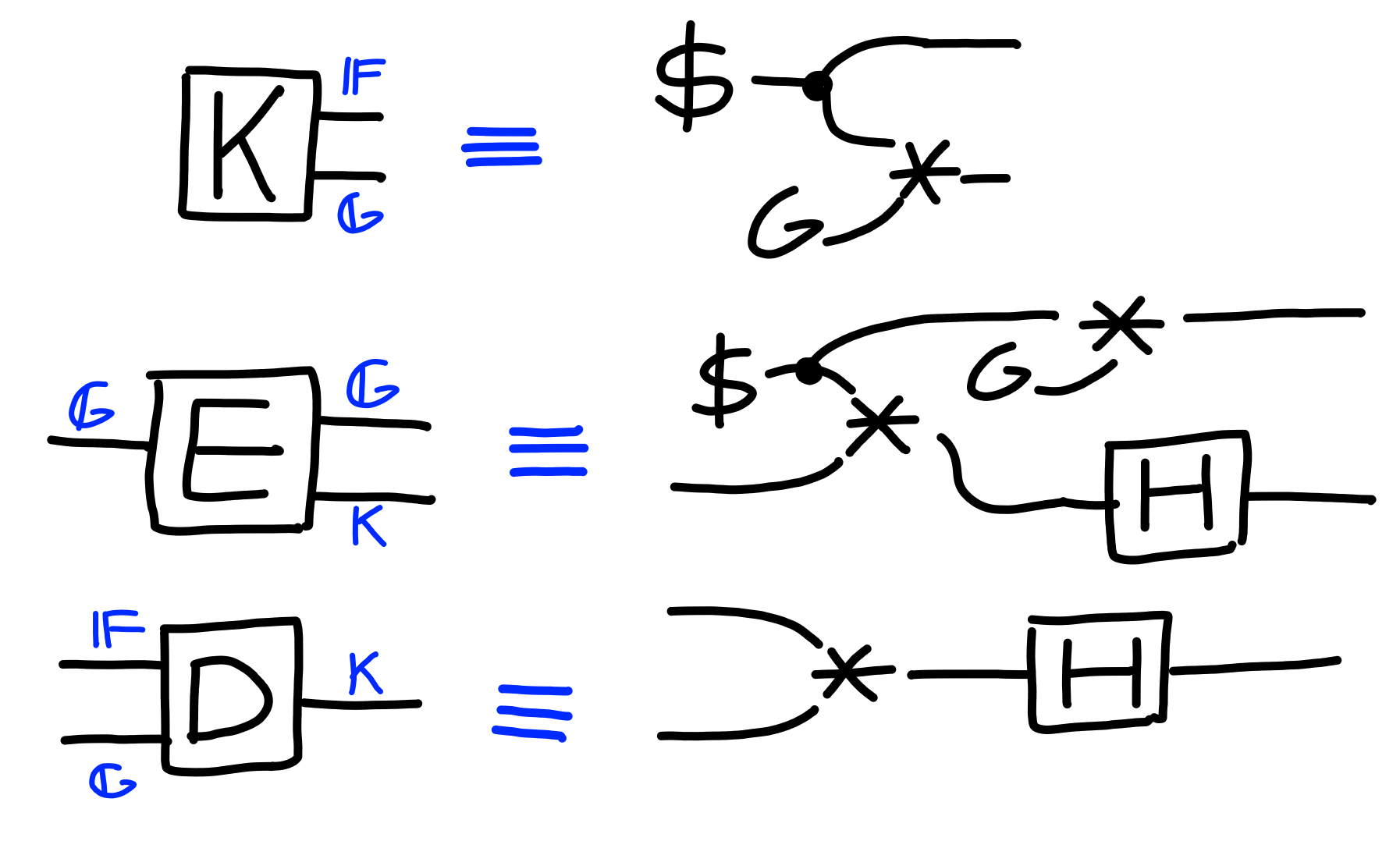

Gates

The selector functions are sufficient to define logic gates.

For example, here’s negation ($\neg$):

And, here’s logical and ($\land$):

Naturally, we can then define all other logical operators by combining these two operations.

We also define natural multivariate versions of these gates, taking more than one input, by chaining them together. E.g. the and of several variables is $((x_1 \land x_2) \land x_3) \land \ldots$.

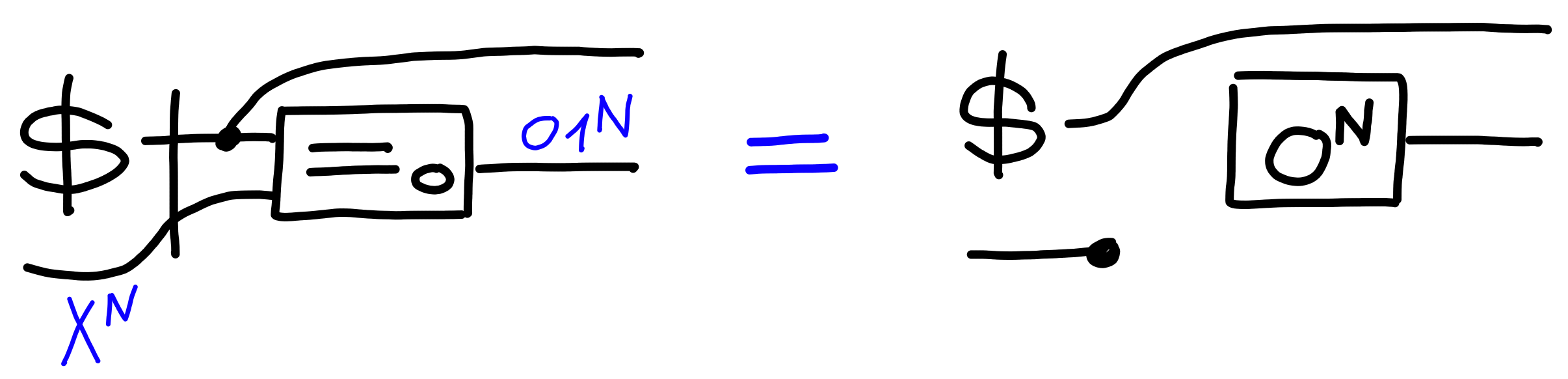

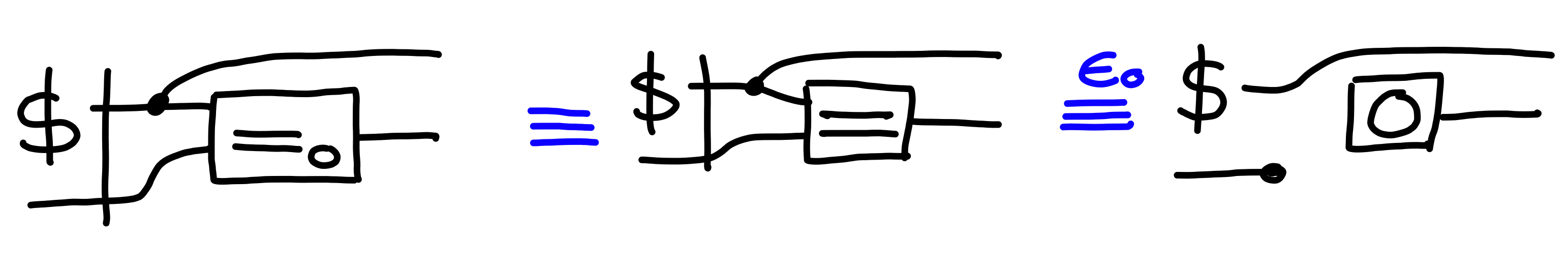

Equalities

Booleans can be produced by different processes, but usually a boolean is produced as the result of some kind of comparison. One very important kind of comparison we’ll be needing is that of equality.

Some types are able to be compared for equality, in which case

the operator “$=$” is defined:

Many times, we’ll want to compare multiple things

against a single thing, which we define via the operator “$=_0$":

This is also our first instance of defining a construction by induction. We define the general case for $N$ inputs by looking at the case with $0$ an inputs, and then at the case where we have one additional input.

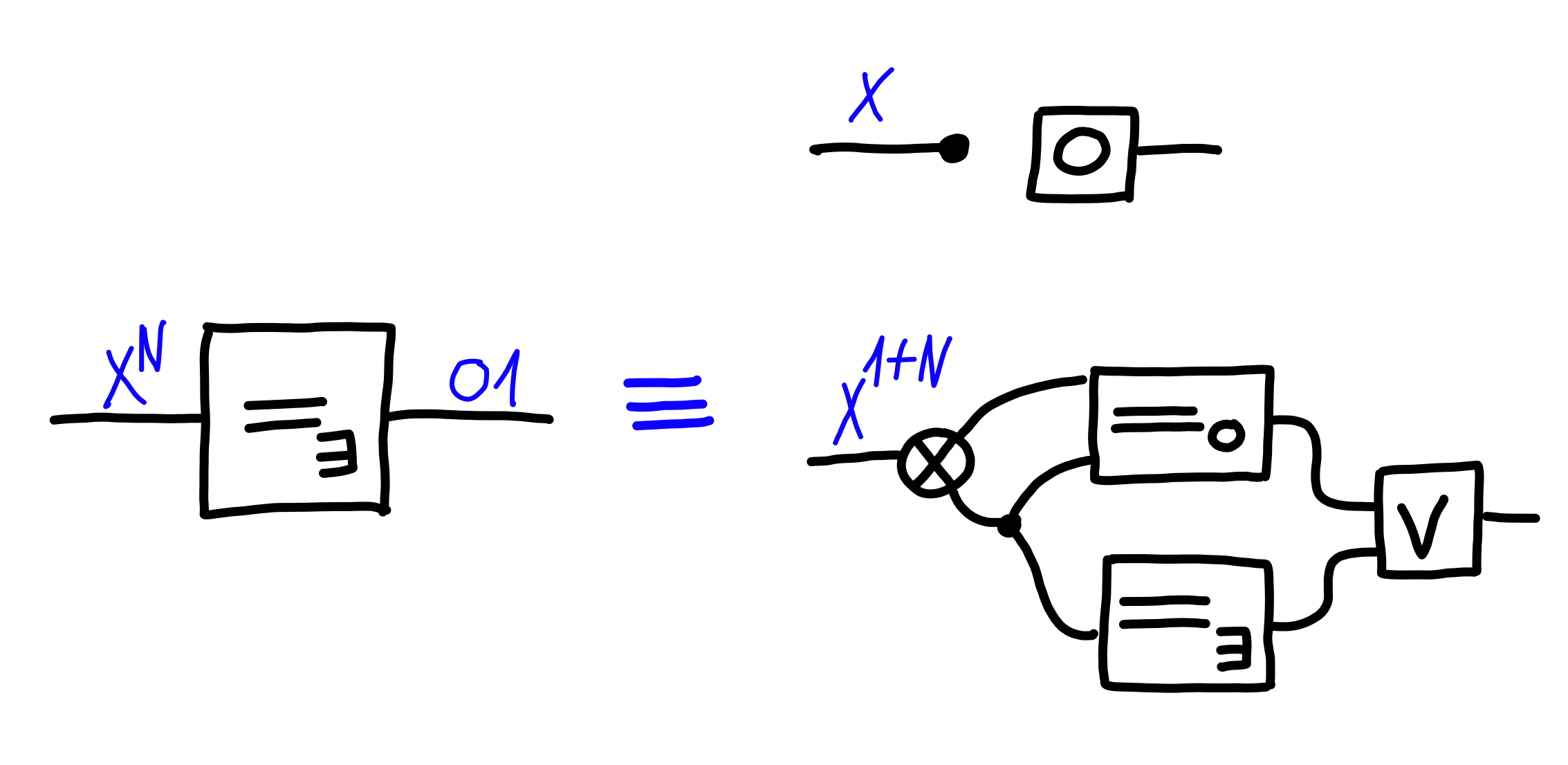

Finally, the last kind of equality we have will check

if any among a list of values is equal to another, via “$=_\exists$":

Equality of Copied Values

Another natural property of equality is that comparing duplicated

elements for equality will always return true:

Randomness

What differentiates cryptography from other fields is ultimately that of randomness. In this section we define some basic properties of randomness, which will be the foundation for the rest of the schemes we see in this post.

Some types are said to be sampleable, when there exists

a process of the form:

Furthermore, some types have some addition operation, $+$,

which as one might expect with randomness:

Guessing

For some types, it’s difficult to guess a value sampled at random, without first seeing that value.

Barriers

In order to formalize “without first seeing”, we introduce the notion of barriers:

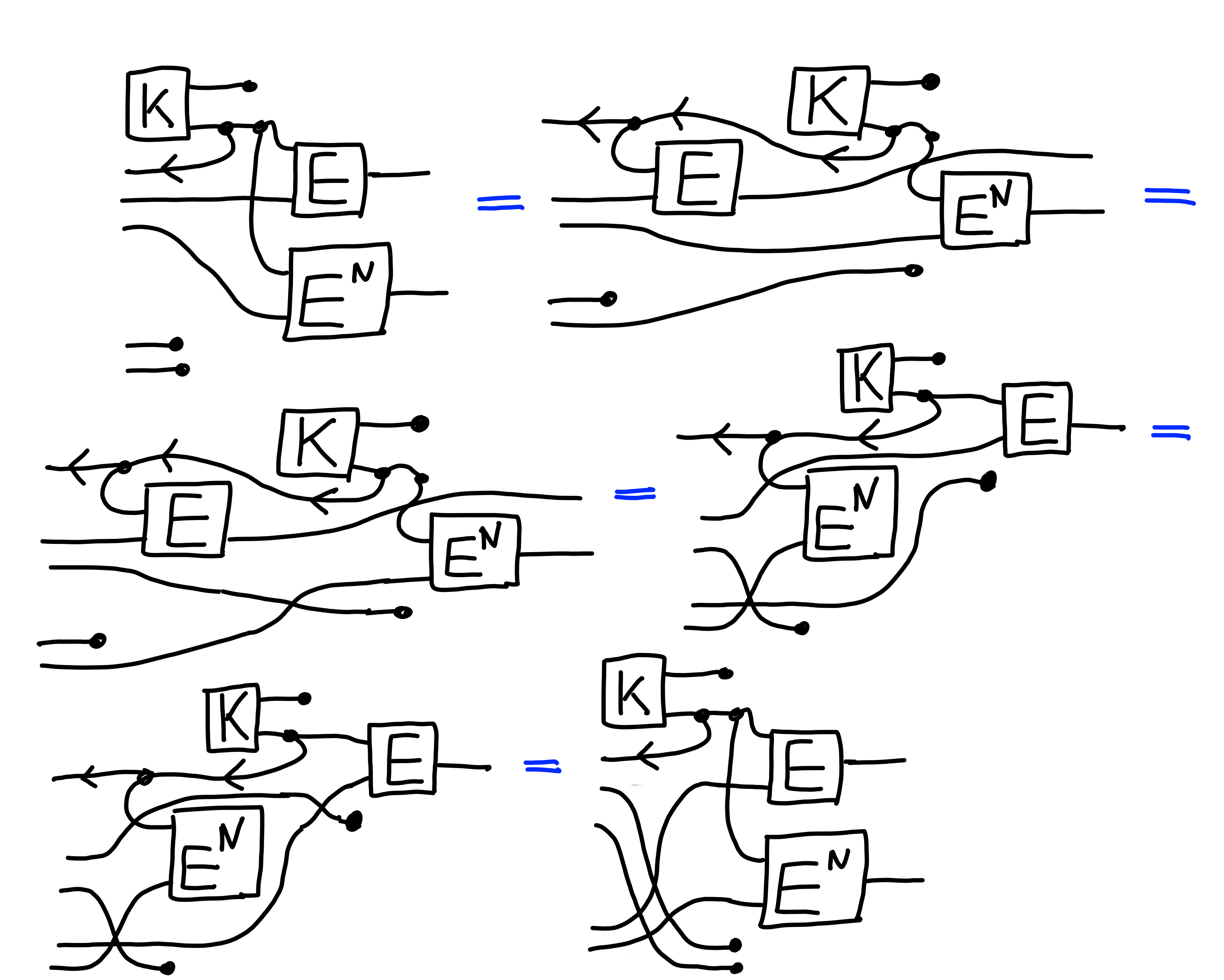

Here are some properties of barriers:

Intuitively, these capture the fact that a barrier can’t be “crossed”, unlike a standard wire, but that a barrier only cares about the “dependencies” of its wires.

Back to Guessing

Now, having defined barriers, let’s go back to the task we had before, which is that of defining what it means to have values which are hard to “guess” if sampled at random. We call such types large, as defined by the following property:

Property: For a type $X$, $\Pi[\text{Guess}(X)]$ is defined via:

$\square$

In other words, for large types, this property will hold. We usually consider it as an explicit assumption though, allowing us to keep track of how many times the assumption is used, and thus choosing a concrete size for the type for it to be large enough in the context of a given system.

The barrier here is crucial, otherwise one could show this property to never hold, by copying the random value and using it as the guess. The barrier prevents this, by forcing the guess to be chosen before the random value is seen.

Implied Equalities

We’ve shown a basic guessing property for a simple equality, but what can we say about guessing properties for more complicated equalities?

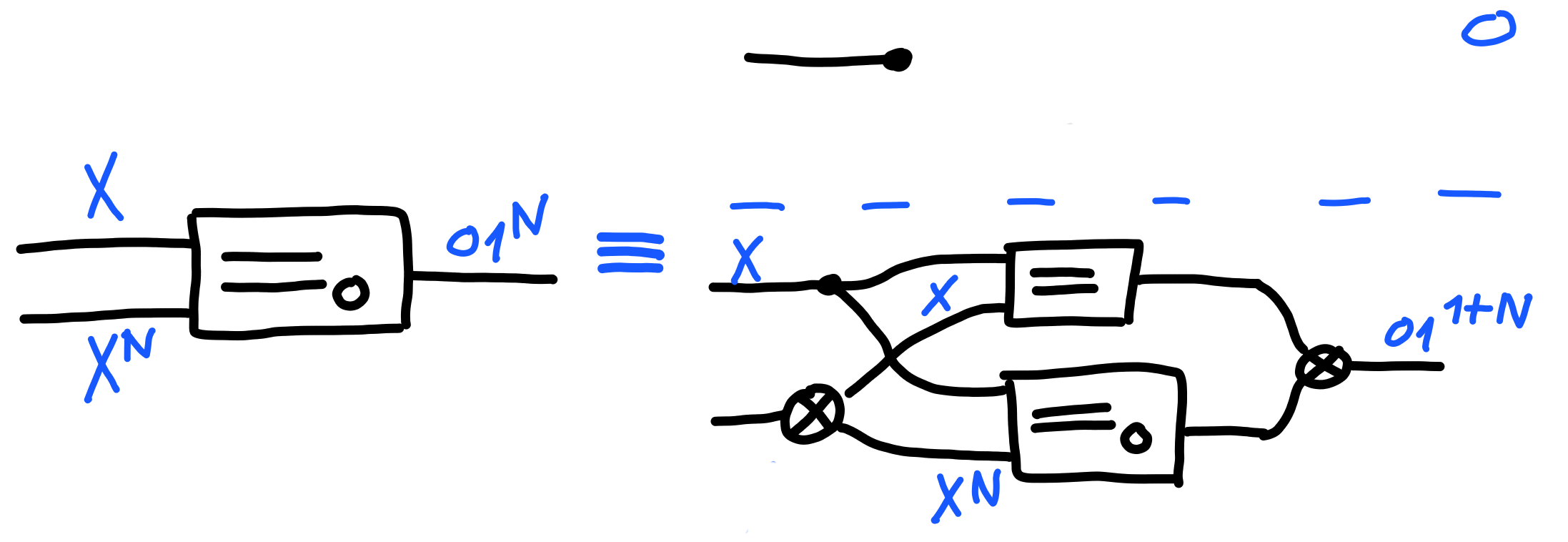

First, for $=_0$, we can set up the property $\Pi[\text{MultiGuess}(N)]$,

saying that guessing is hard, even with multiple guesses:

As one might expect, if guessing with one try is hard, so is it with multiple tries.

Claim: $$ \Pi[\text{Guess}]^N \multimap \Pi[\text{MultiGuess}(N)] $$ Proof:

We proceed by induction.

First, we prove that $\Pi[\text{Guess}] \multimap \Pi[\text{MultiGuess}(1)]$:

Next, we prove that $\Pi[\text{Guess}] \otimes \Pi[\text{Guess}]^N \multimap \Pi[\text{MultiGuess}(1 + N)]$:

$\blacksquare$

This property will be useful in many contexts where we want to use a random value more than once.

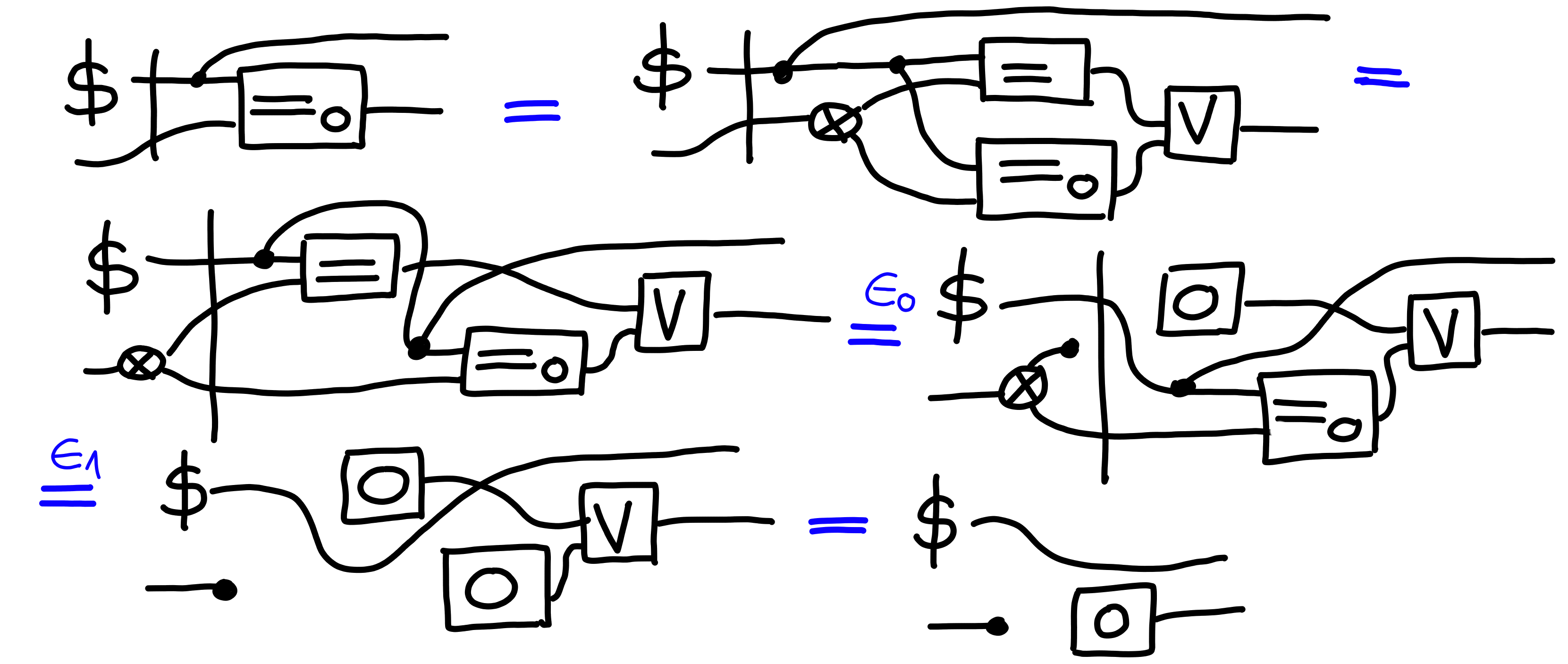

Random Functions

Next, we develop a little gadget we’ll be using a few times throughout this post: random functions. Random functions are useful to define the random oracle model of security, and to define pseudo-random functions, which we’ll use for encryption.

Mathematically, a random function $f : X \to Y$ is like sampling a value from that set of functions randomly. The outputs of $f$ will be random, subject to the condition that $x = x' \implies f(x) = f(x')$.

This perspective is a bit cumbersome in that it doesn’t give us an easy algorithmic recipe to construct such a random function. We need a succinct way to do that. A useful perspective here is that we can look at making a random function a lazy mapping. Each time we produce an output, we check if the input has been seen before, in which case we use a previous output, otherwise we generate a fresh random output.

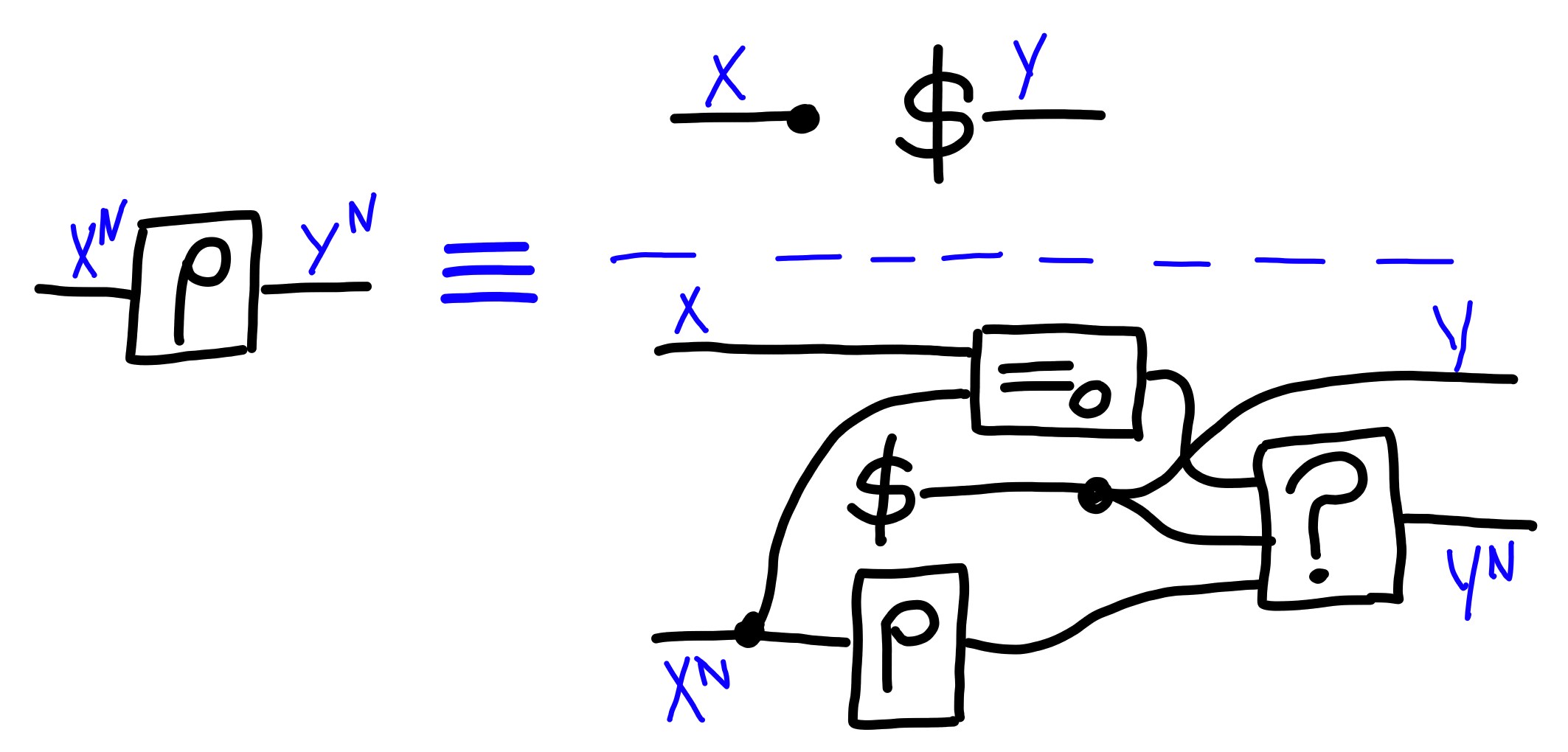

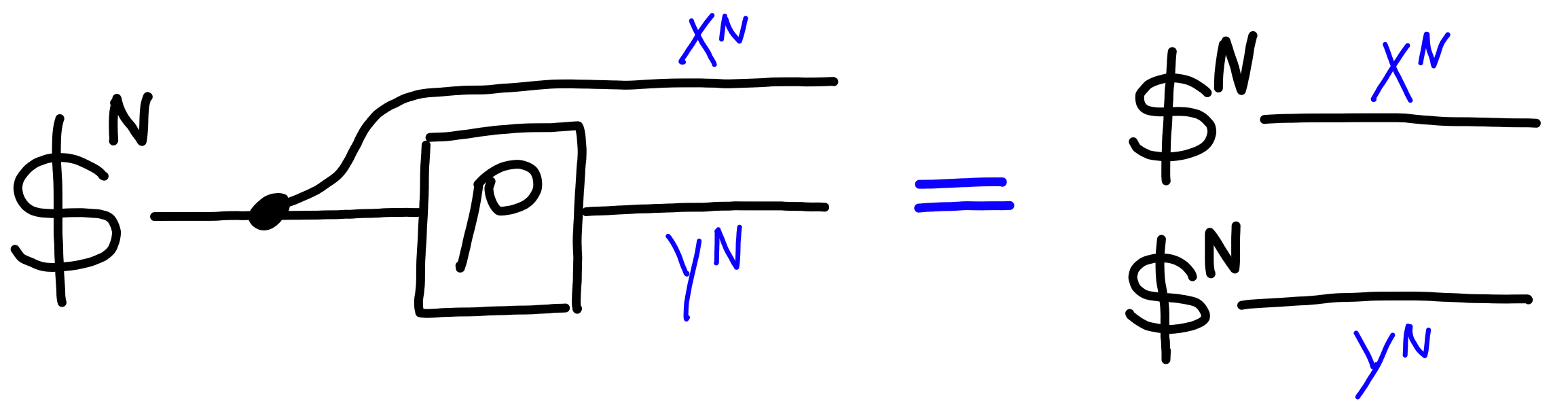

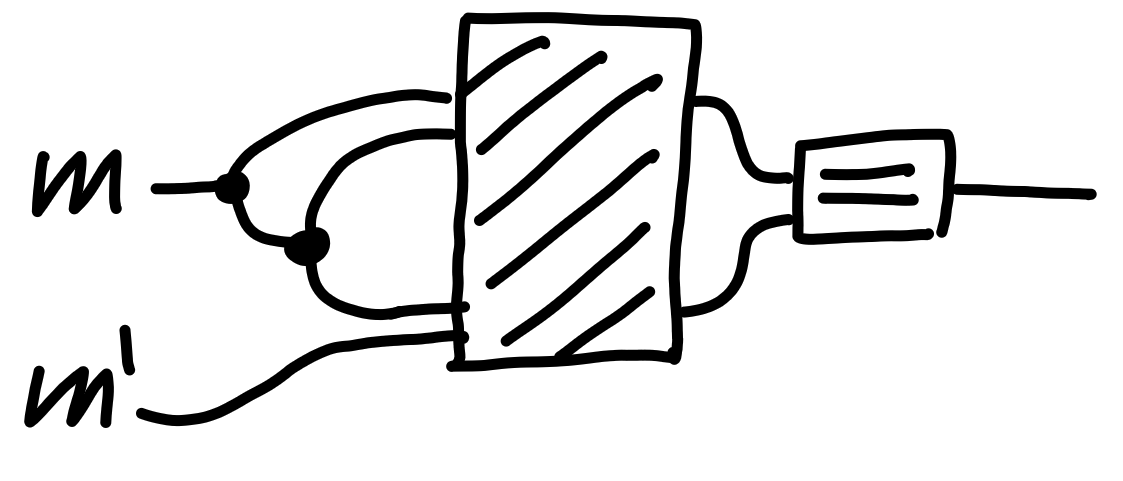

This leads us to the following definition of a random function

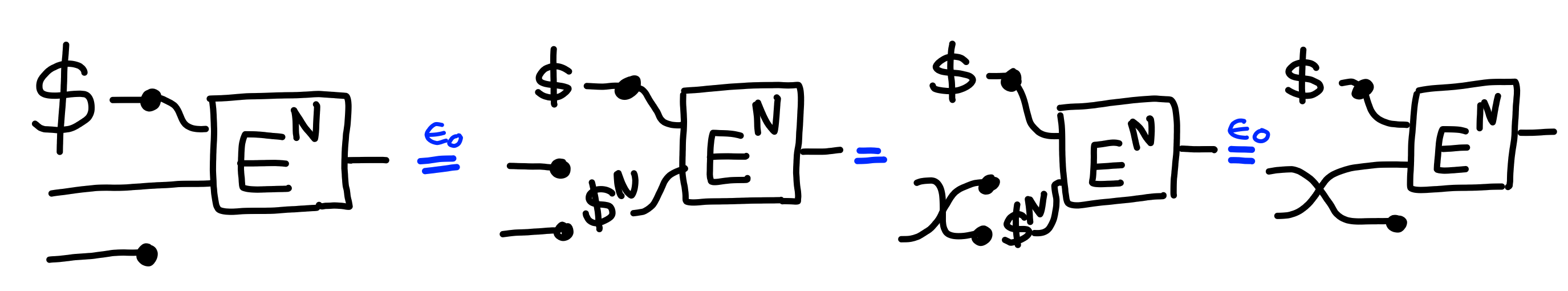

over $N$ inputs, $\rho$:

Random Functions on Random Inputs

The outputs of a random function are basically random,

except if the inputs have collisions.

If the inputs are random, then collisions will be unlikely,

as the following property,$\Pi[\rho\text{Rand}(N)]$, claims:

This claim can be proven for large types.

Claim: $\bigotimes_{i = N,\ldots,1}\Pi[\text{MultiGuess}(i)] \multimap \Pi[\rho\text{Rand}(N)]$

Proof:

By induction.

$\Pi[\text{MultiGuess}(1)] \multimap \Pi[\rho\text{Rand}(1)]$:

$\Pi[\text{MultiGuess}(1 + N)] \otimes \Pi[\rho\text{Rand}(N)] \multimap \Pi[\rho\text{Rand}(1 + N)]$:

$\blacksquare$

If we combine this with what we know about $\Pi[\text{MultiGuess}(N)]$, we get that $\Pi[\text{Guess}]^{N^2} \multimap \Pi[\rho\text{Rand}(N)]$.

This is a very useful property, as it shows that applying a random function to random inputs produces completely independent random outputs as well.

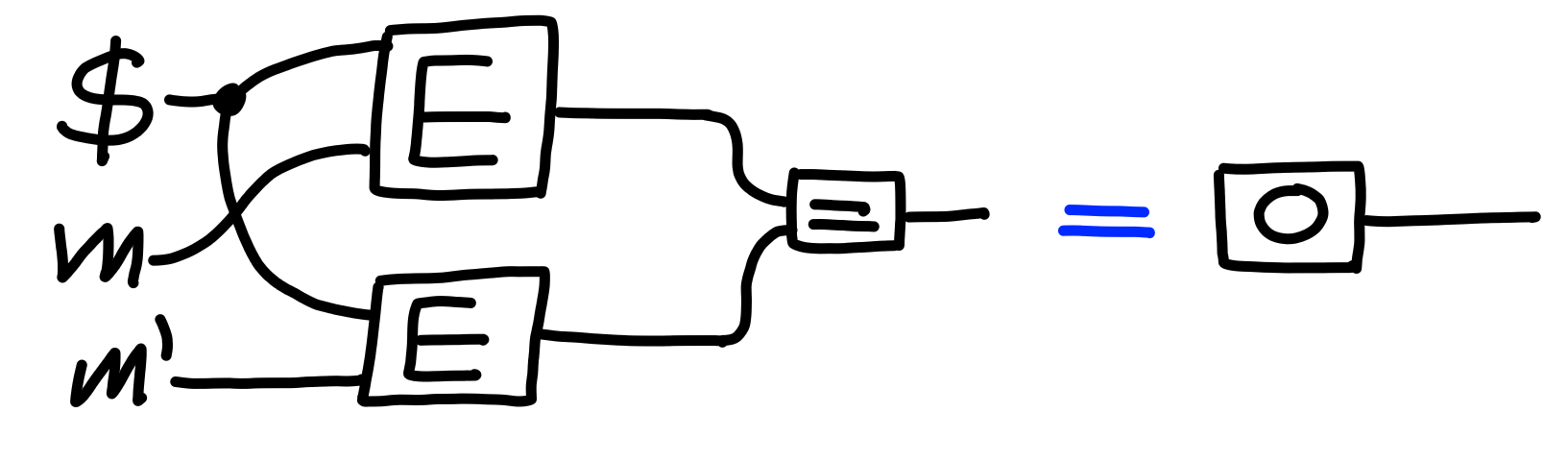

Encryption

Next, we turn our eyes towards symmetric-key encryption. In this kind of encryption, both the sender and the receiver share a random value: the key. Using the key, there’s an algorithm to encrypt a message, producing a ciphertext. Given a ciphertext, one can decrypt it using the key to recover the message. For security, one shouldn’t be able to learn any information about the message just by looking at the ciphertext.

More formally, an encryption scheme is a randomized function: $$ E : K \otimes M \xrightarrow{\$} \to C $$ for a type of keys $K$, of messages $M$, and ciphertexts $C$, along with a deterministic function: $$ D : K \otimes C \to M $$

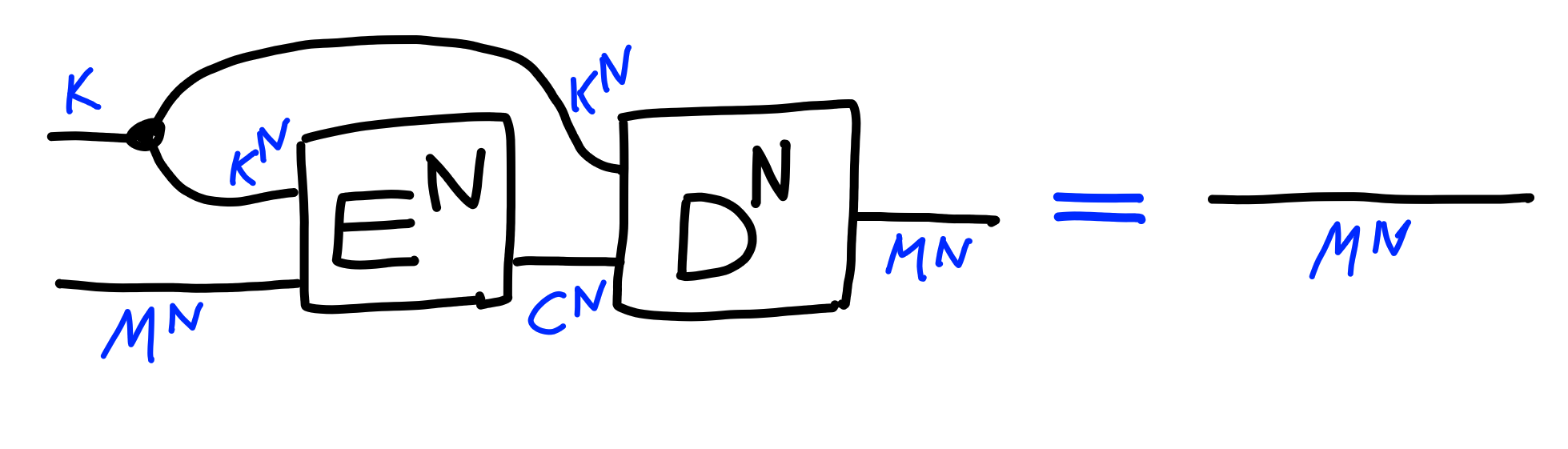

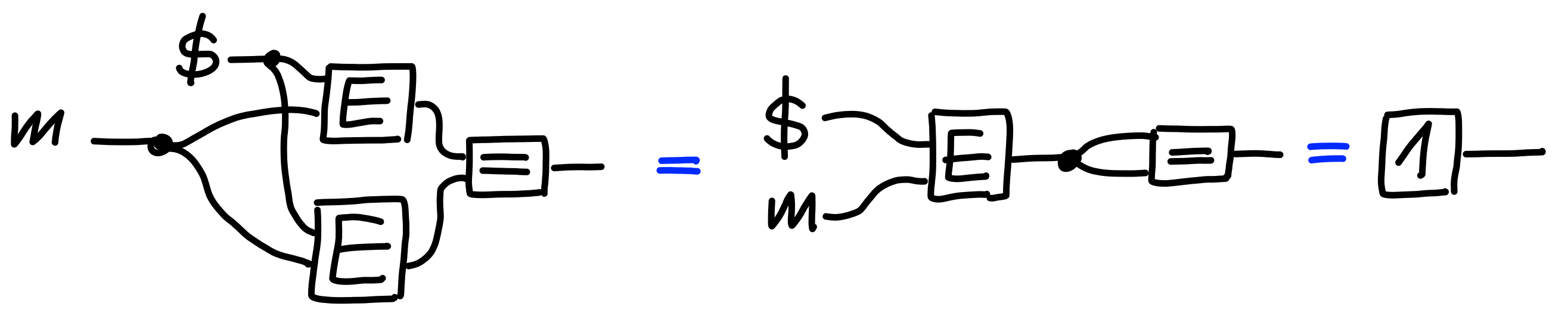

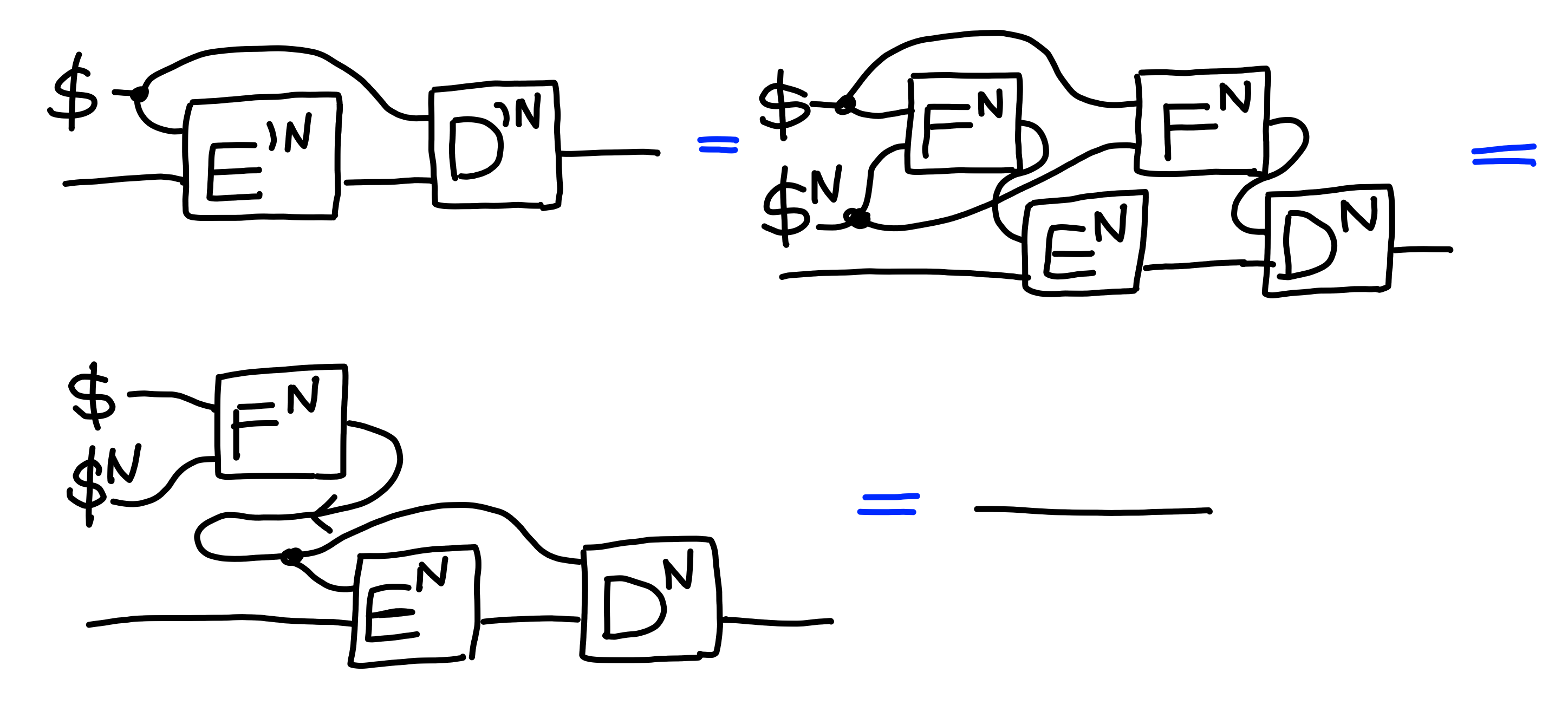

We require the following correctness property of an encryption scheme:

Indistinguishability

Informally, the security of encryption says that “no information”

can be extract from a ciphertext.

Formally, we model this via the property $\Pi[\text{IND-CPA}(N)]$:

Often we refer to the property $\Pi[\text{IND-CPA}(1)]$ as $\Pi[\text{IND}]$. Achieving the latter is much easier than achieving the former for arbitrary $N$, as we’ll see later.

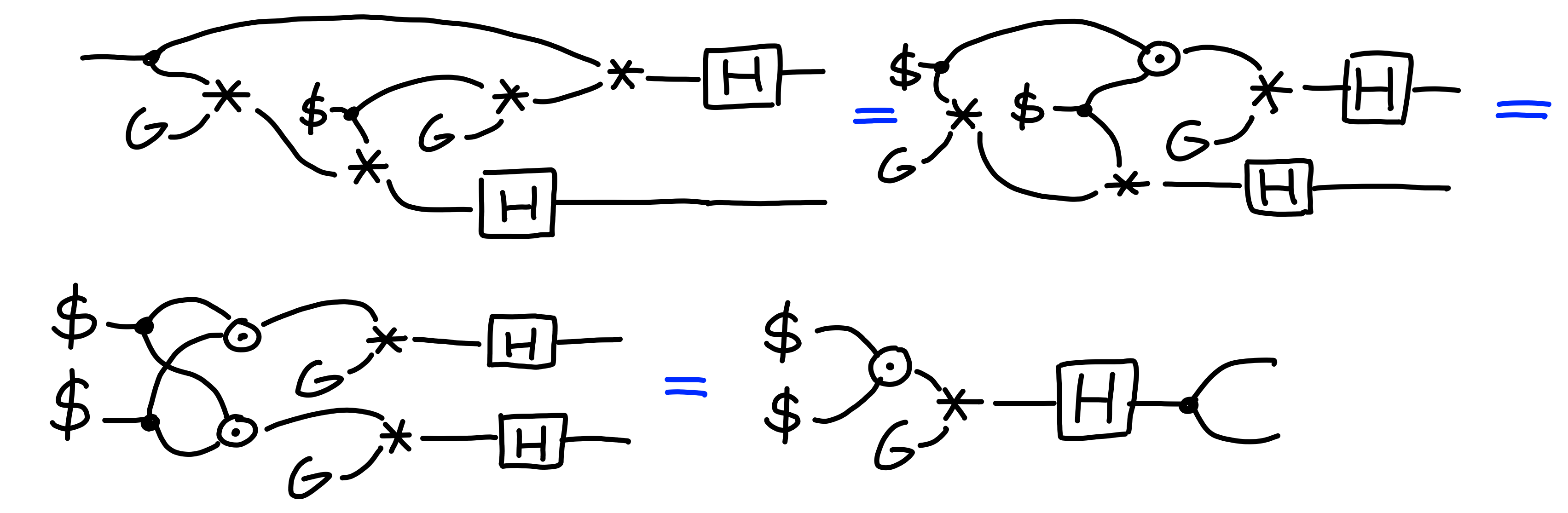

Left or Right vs Real or Random

Another variant of security for encryption involves

comparing the encryption of a chosen set of messages,

and that of a random set of messages, as described by the property

$\Pi[\text{\$IND-CPA}(N)]$:

This turns out to be equivalent.

The first direction is trivial:

Claim:

$$

\Pi[\text{IND-CPA}(N)] \multimap \Pi[\text{\$IND-CPA}(N)]

$$

Proof:

The second direction is a bit less trivial, in that we need to use the assumption twice.

Claim:

$$

\Pi[\text{\$IND-CPA}(N)]^2 \multimap \Pi[\text{IND-CPA}(N)]

$$

Proof:

Because of this, we’ll often use one of these properties as is more convenient, since the difference between them doesn’t really matter.

One-Time Pad

Now, we construct an example of a scheme that satisfies the $\Pi[\text{IND}]$ property.

To do so, we introduce the notion of a “binary” type.

This is a large type $X$, along with an operation

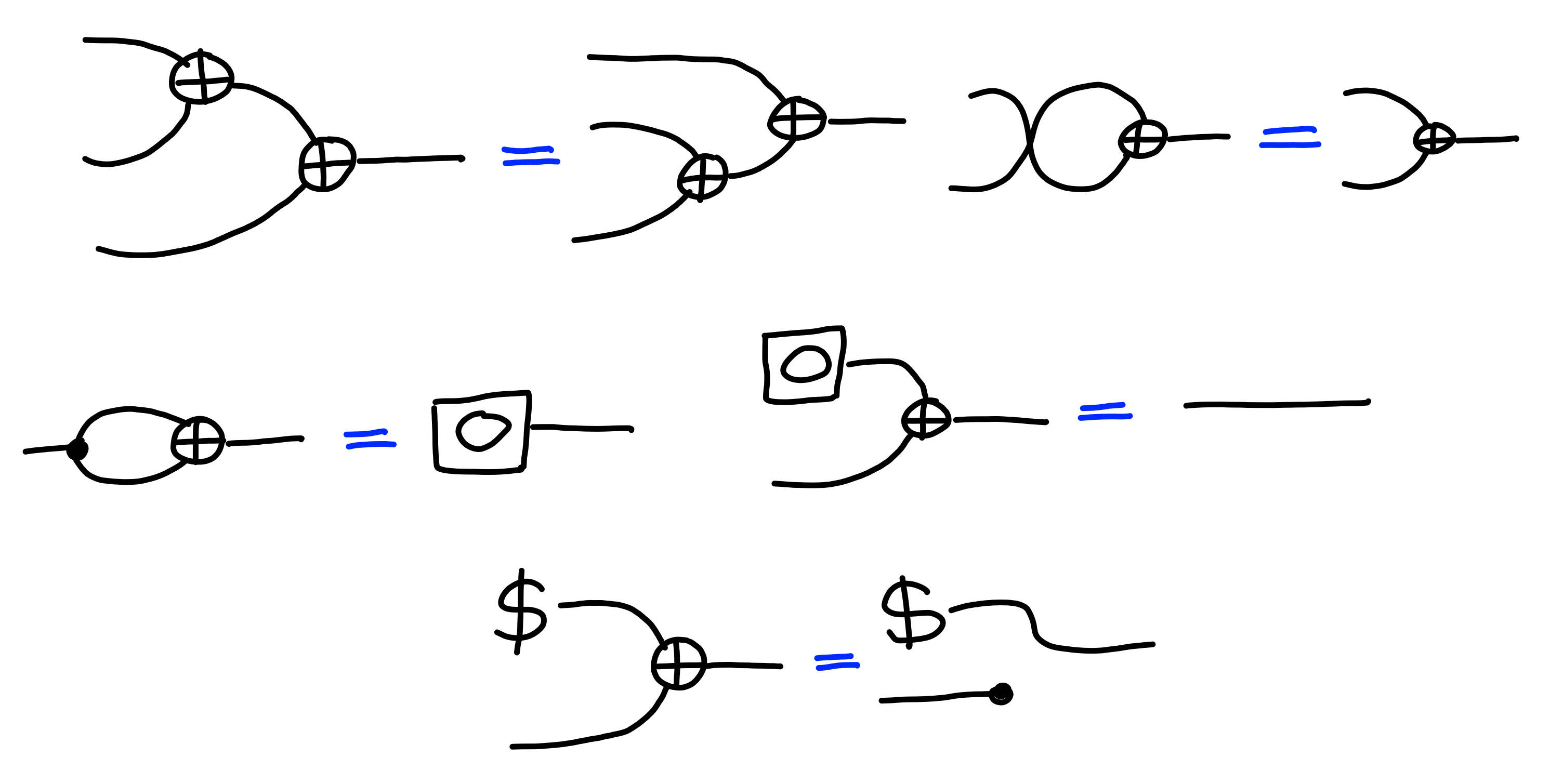

$\oplus : X \otimes X \to X$,

and an element $0 : X$, satisfying the following properties:

An example of this would be some set of binary strings $\{0, 1\}^\lambda$, with the usual xor operation. The rules above just say that $\oplus$ is an associative and commutative operator, with the extra property that any element $\oplus$ itself is the identity. Also, we have a property related to randomness, which says that xoring a random value with any other value results in a random value.

This property is precisely what we’ll use to make an encryption scheme. The idea is that our keys, messages, and ciphertexts will all be of type $X$, and we encrypt a message by xoring it with a key.

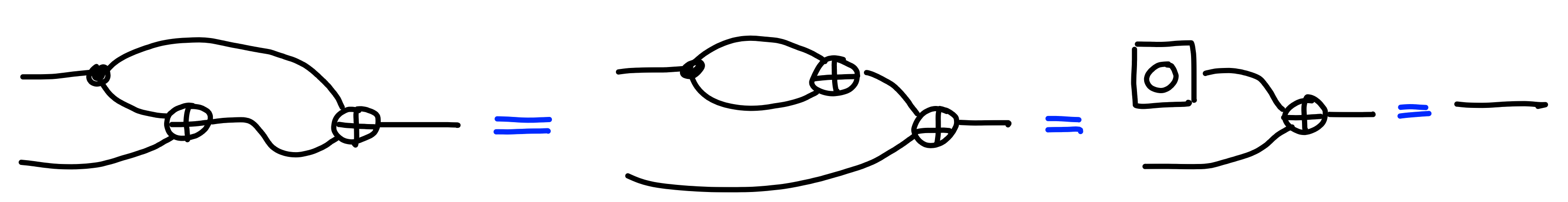

We can check that this satisfies the correctness property for encryption:

Against multiple queries, we do run into a problem though.

Intuitively, with multiple ciphertexts, we can calculate

the xor of two messages:

Deterministic Schemes aren’t IND-CPA Secure

We can generalize the issue at hand, and show that any deterministic encryption scheme will fail to be secure against multiple encryption queries.

A deterministic process satisfies the following property:

In the case of encryption, a deterministic scheme (relative to a fixed key)

will then satisfy this property like so:

Now, let’s say that we have two messages $m, m'$ such that they result

in different ciphertexts (for xor, $m \neq m'$ suffices):

We can then use that to show that the two processes

in $\Pi[\text{IND-CPA}(2)]$ are different.

This property claims the following equality:

Now, consider the following “strategy” wrapped around the

black box shape of this property:

If we have the left side of the property,

this becomes:

On the right side of the property,

we use the second pair, which by assumption

will produce inequal ciphertexts, giving us:

Now, since $0$ and $1$ are not equal as processes, this property cannot hold, at least for deterministic encryption schemes.

Achieiving Multiple Encryptions

Now, we move our attention to actually fixing this issue, and achieving security against multiple encryption queries. The approach we’ll use here is actually a bit clever. If you were to take a scheme that’s secure against one encryption query, then that would imply that it would be secure against many queries, as long as you could use a new key each time (we’ll prove this later). Now, we could try generating a fresh key each time, the issue is that the decryption algorithm only has access to the original key, and the ciphertext, and thus would not have access to this fresh key, breaking the correctness of our scheme.

We can fix this by somehow being able to “hide” the fresh key inside of the ciphertext, such that the information the decryption scheme has will be enough to recover it.

Pseudo-Random Functions

This is where pseudo-random functions, or PRFs, come in. The idea is that a PRF is a deterministic algorithm taking in a secret key, but which behaves identically to a random function, if you don’t know the key. This allows us to solve our conundrum: we can place a unique value, called a nonce, inside each ciphertext (for example, by generating it at random), which will then make the output of the PRF effectively random, thus providing a fresh key to use for encryption.

A Formal Definition

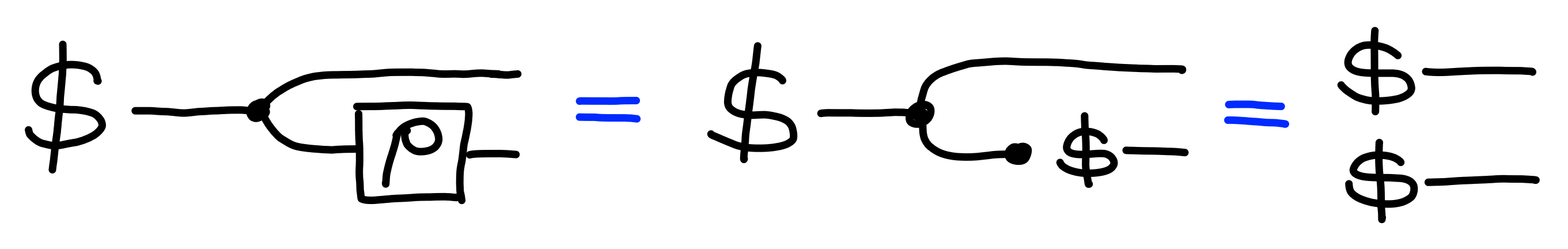

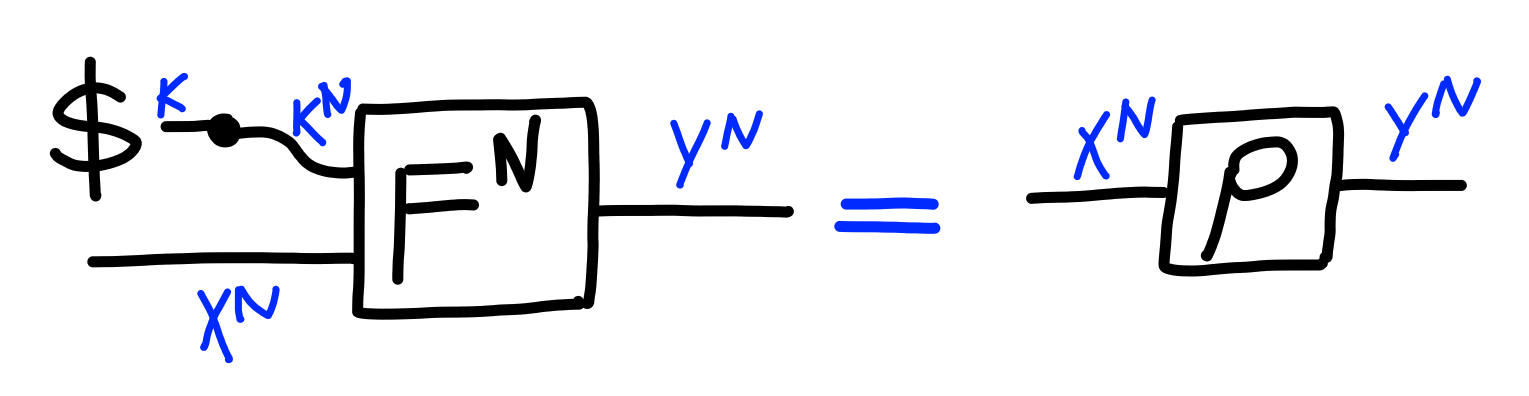

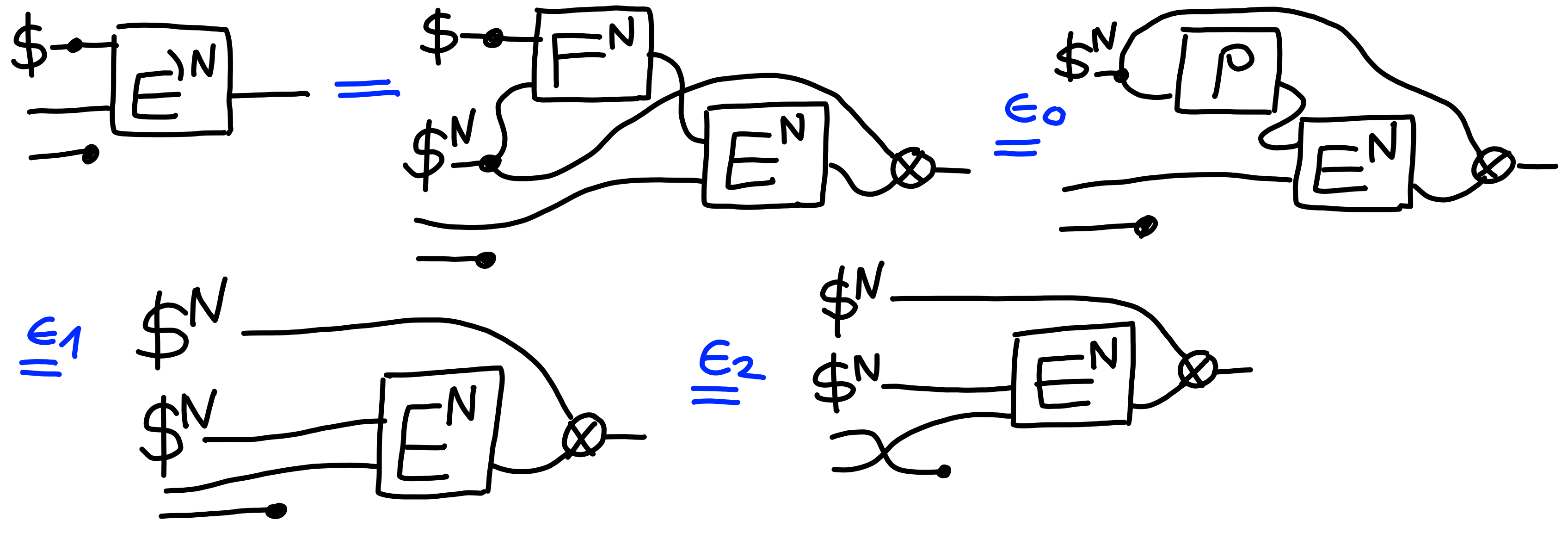

More formally, a PRF from $X$ to $Y$ is a deterministic function $F : K \otimes X \to Y$, over a type of key $K$.

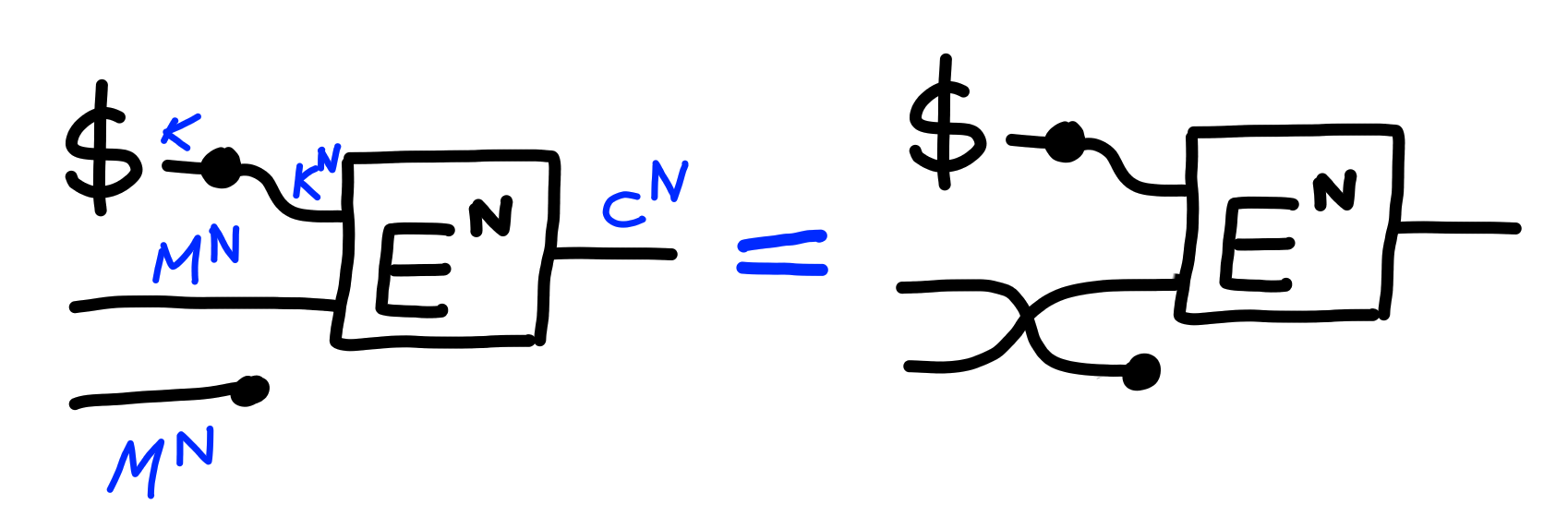

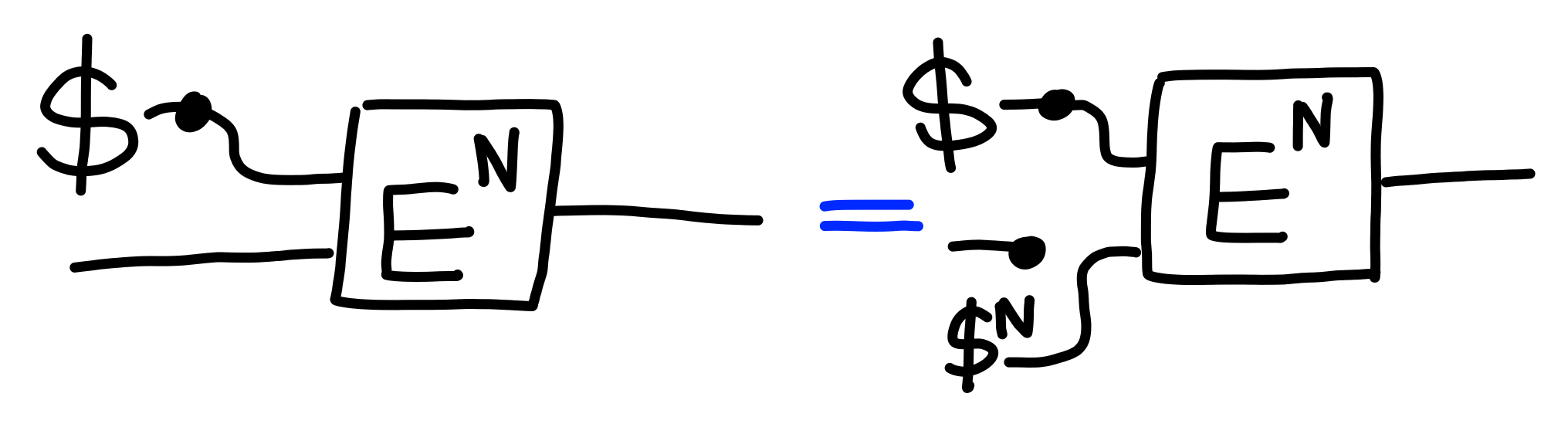

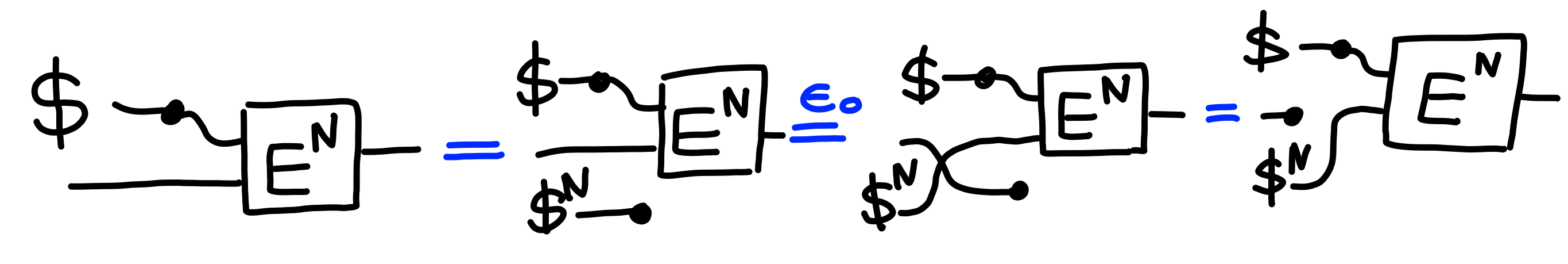

The security property of a PRF is quite simple, namely that

it behaves like a random function if the key is selected

at random and not revealed, as described by $\Pi[\text{PRF}(N)]$:

IND-CPA Encryption from PRFs

Next, we follow the roadmap we sketched above to construct an IND-CPA secure encryption scheme from an IND secure scheme.

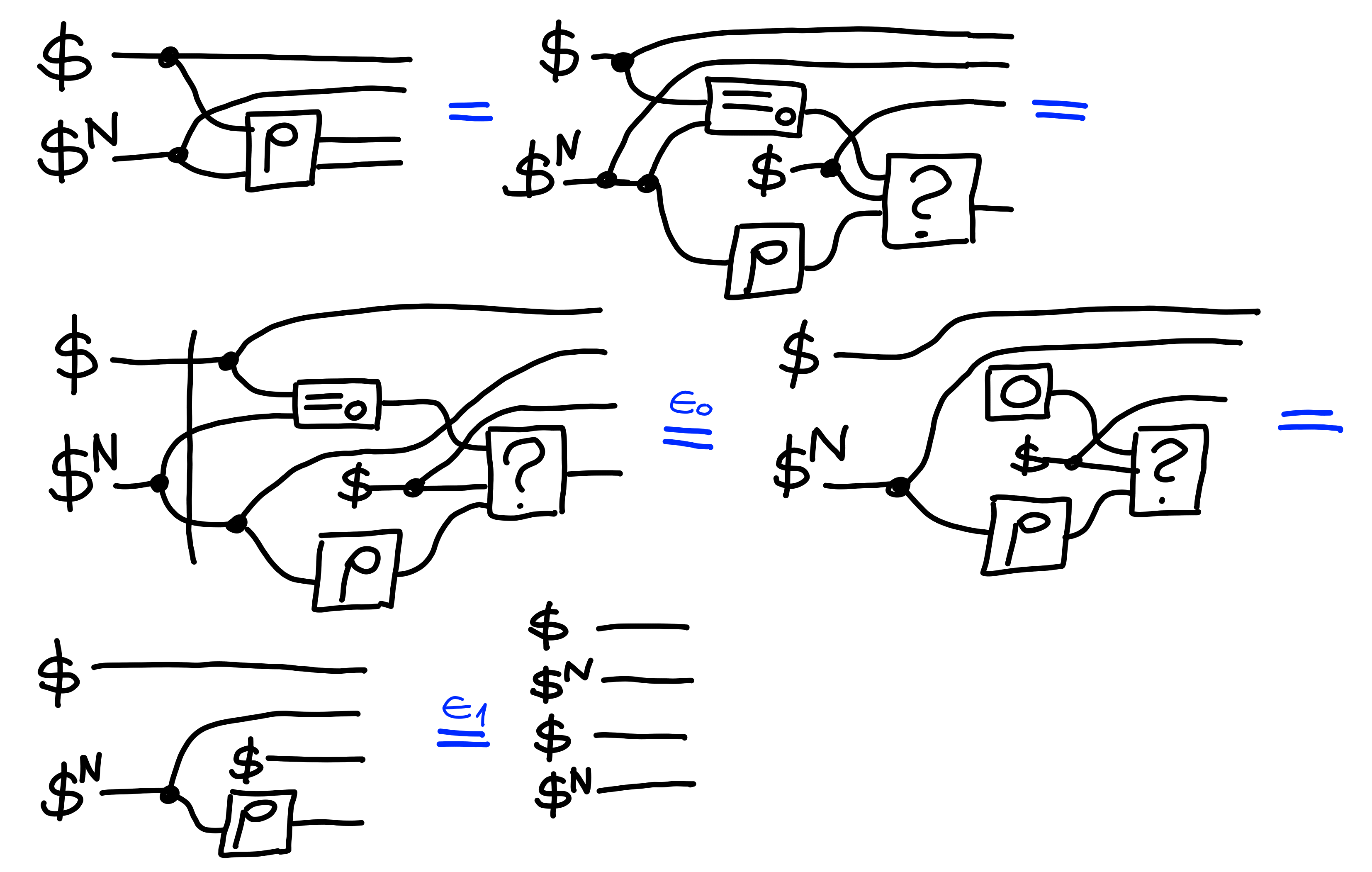

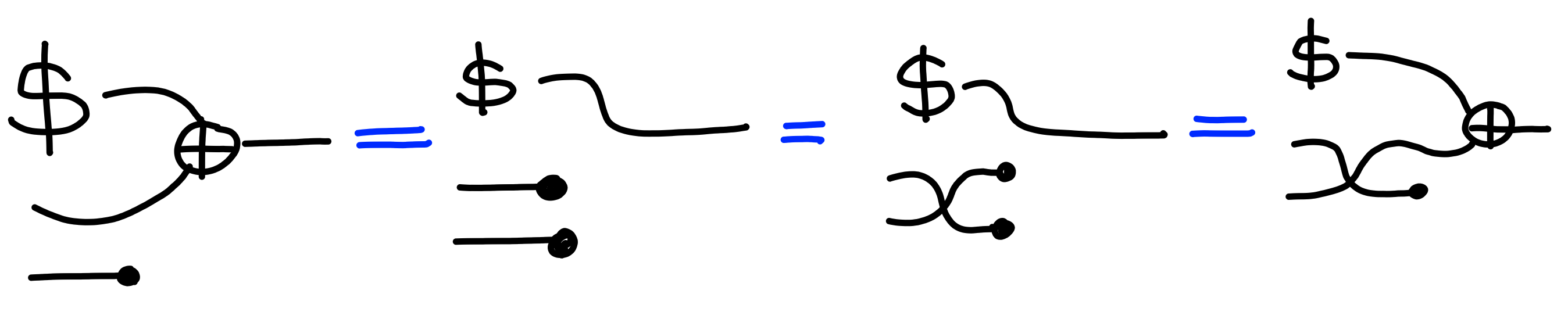

First, we consider the property $\Pi[\text{Multi-IND}(N)]$:

This property follows in a natural way from the single key case:

Claim: $$ \Pi[\text{IND}]^N \multimap \Pi[\text{Multi-IND}(N)] $$ Proof:

By induction. $$ \Pi[\text{IND}] \multimap \Pi[\text{Multi-IND}(1)] $$ trivially, since both properties are the same.

$$

\Pi[\text{IND}] \otimes \Pi[\text{IND}]^N \multimap \Pi[\text{Multi-IND}(1 + N)]

$$

(This is a specific case of a general theorem saying that $(A = B)^n \multimap A^n = B^n$.)

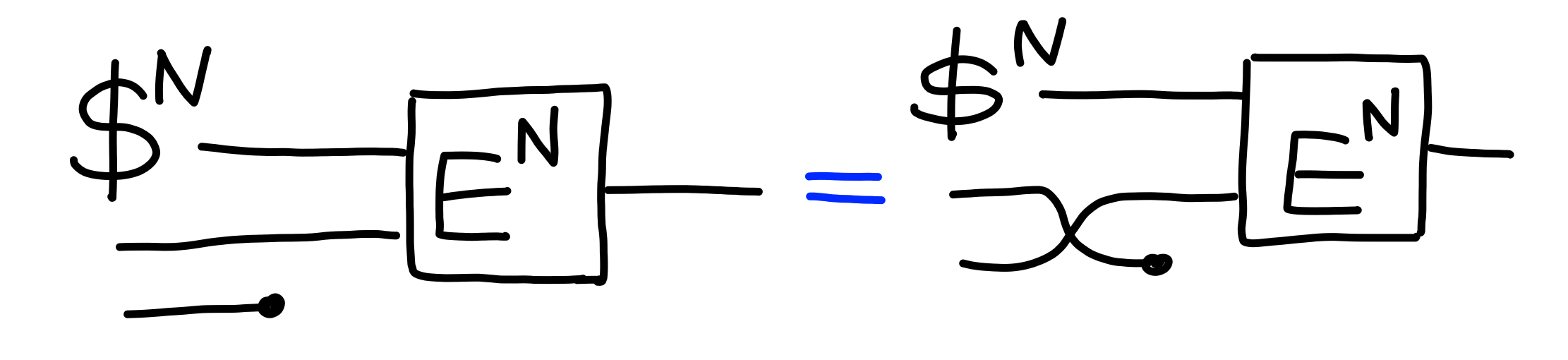

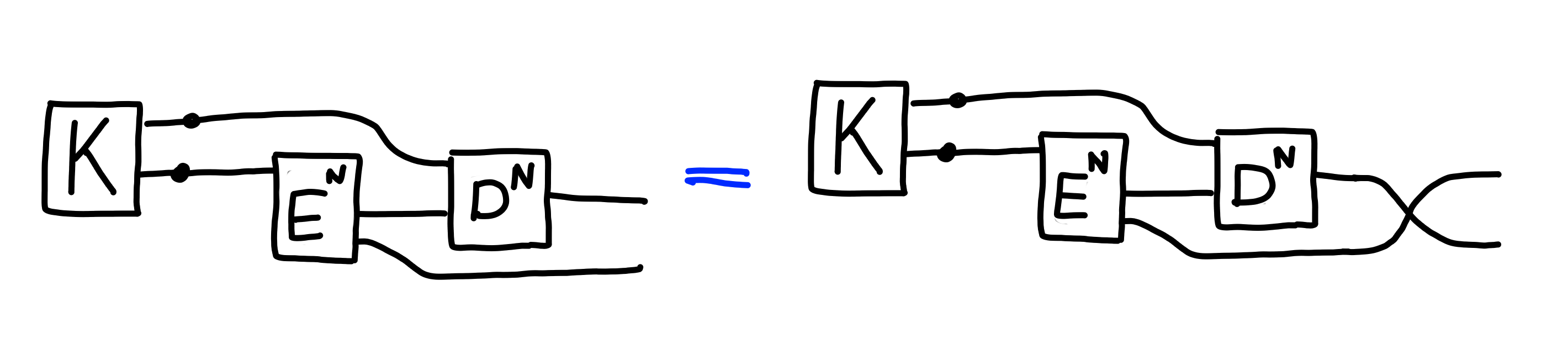

Now, given an encryption scheme $$ E : K_0 \otimes M \to C $$, and a PRF $$ F : K_1 \otimes X \to K_0 $$ , we construct an encryption scheme $$ E' : K_1 \otimes M \to (X \otimes C) $$.

The idea is that $X$ will be the type of our “nonce”, which will be generated

at random and appended to the ciphertext:

We can see that this encryption scheme is correct,

using the fact that $F$ is deterministic:

All that’s left is to prove that this scheme is secure.

Claim::

$$ \Pi[\text{PRF}(N)]^2 \otimes \Pi[\rho\text{RAND}(N)]^2 \otimes \Pi[\text{Multi-IND}(N)] \multimap \Pi[\text{IND-CPA}(N)] $$ Proof:

$\blacksquare$

Public-Key Encryption

Next, we move from symmetric encryption to public key encryption.

In symmetric encryption, encryption and decryption use the same key, which must be kept secret.

In public key encryption, encryption and decryption use different keys. Encryption only requires a public key, which, as the name suggests, can be public, whereas decryption requires a secret key (and sometimes also the public key), which must be kept secret.

This allows anyone to encrypt messages to a recipient, but only for that recipient to decrypt messages sent to them.

More formally, a public key encryption scheme consists of:

- Types for public keys $\text{PK}$, private keys $\text{SK}$, messages $M$, and ciphertexts $C$.

- A key generation algorithm $K : \emptyset \xrightarrow{\$} (\text{SK}, \text{PK})$

- An encryption algorithm $E : \text{PK} \otimes M \xrightarrow{\$} C$.

- An encryption algorithm $D : \text{SK} \otimes C \to M$.

The following correctness property must be satisfied:

(This is analogous to the case of symmetric encryption.)

The security property is similar to that of symmetric key encryption,

except that the public key is also leaked:

Now, in this setup, we allow multiple queries.

But, it turns out that it’s equivalent to allow just one query,

as we can show by induction:

Thus, we only consider the single query variant of this property, which we define as $\Pi[\text{PK-IND}]$.

KEM-DEM paradigm

A common way of constructing public key encryption schemes for large messages is to first use a public key encryption scheme to send a key, and then to use that key to encrypt a large message with a symmetric encryption scheme.

There are usually two reasons to do this:

- Setups for public key encryption usually can’t handle large messages.

- Even if they can, public key operations are much slower than symmetric ones.

If you only need to transmit a key to another party, rather than being able to encrypt arbitrary messages to a public key, then you can use a slightly weaker primitive, called a key encapsulation mechanism, or KEM.

KEMs

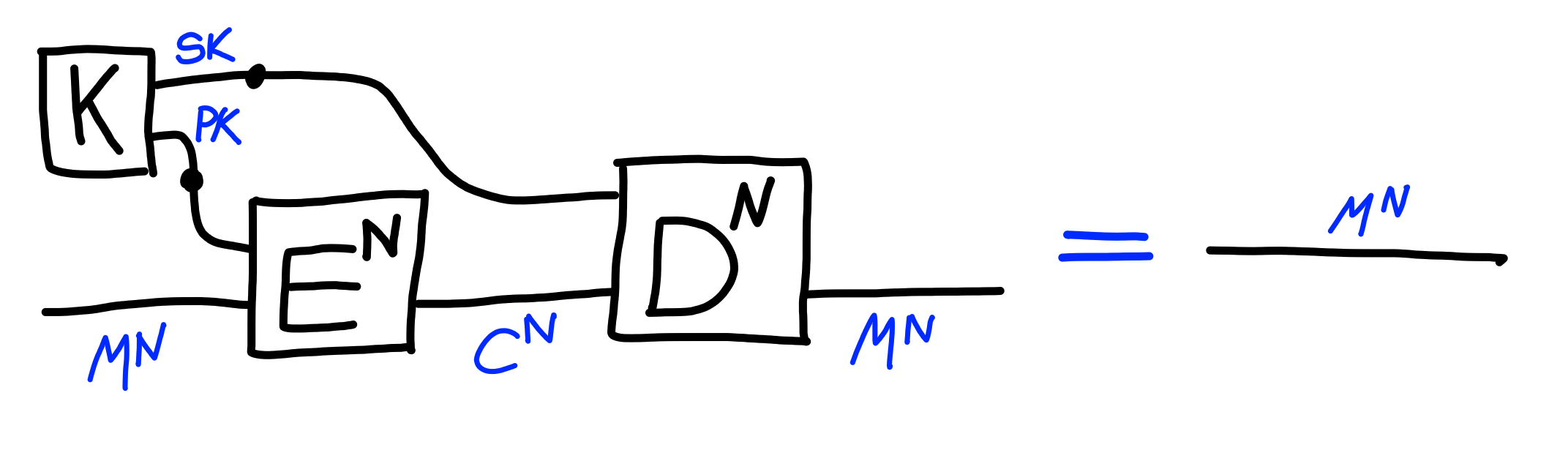

Formally, a KEM consists of:

- Types $\text{PK}$ (public keys), $\text{SK}$ (private keys), $\text{C}$ (ciphertexts / encapsulations), $\text{K}$ (output keys).

- A key generation algorithm $K : \emptyset \xrightarrow{\$} (\text{SK}, \text{PK})$

- An encapsulation algorithm $E : \text{PK} \xrightarrow{\$} C \otimes K$.

- A decapsulation algorithm $D : \text{SK} \otimes C \to K$.

The idea is that the encapsulation algorithm will generate a new key,

along with an encapsulation that hides it.

Then, the secret key allows one to recover the key inside an encapsulation.

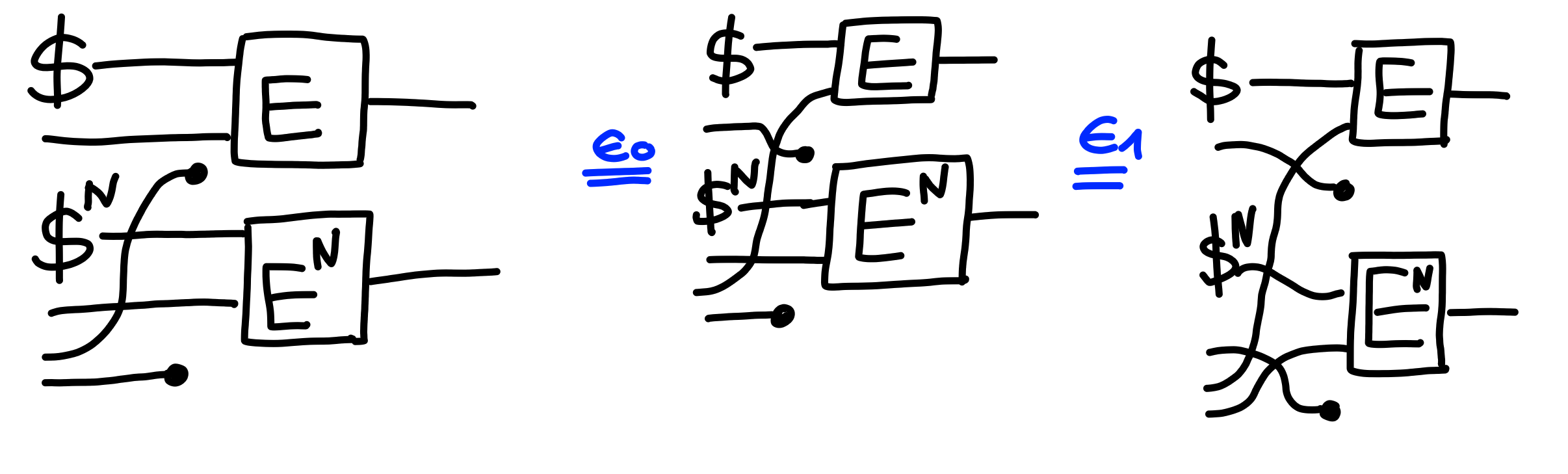

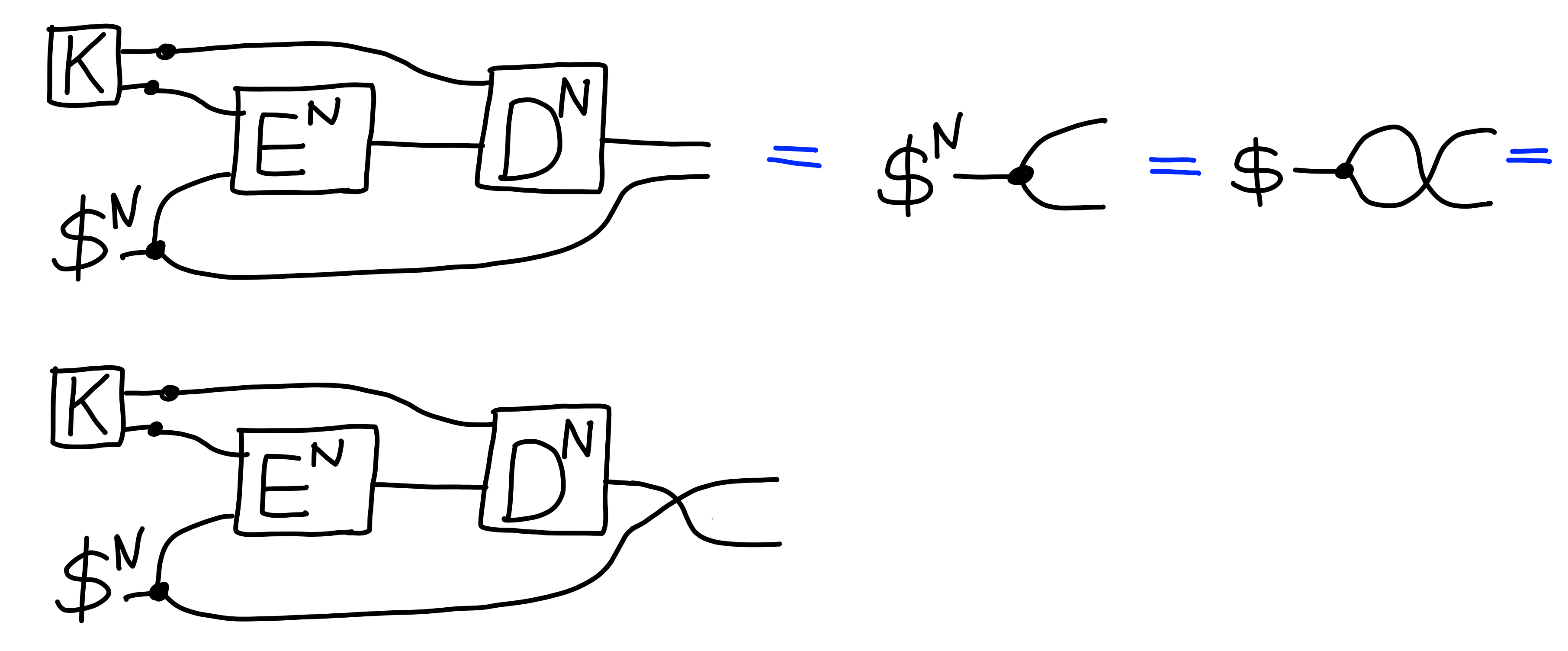

For correctness, we require that the key we get when encapsulating

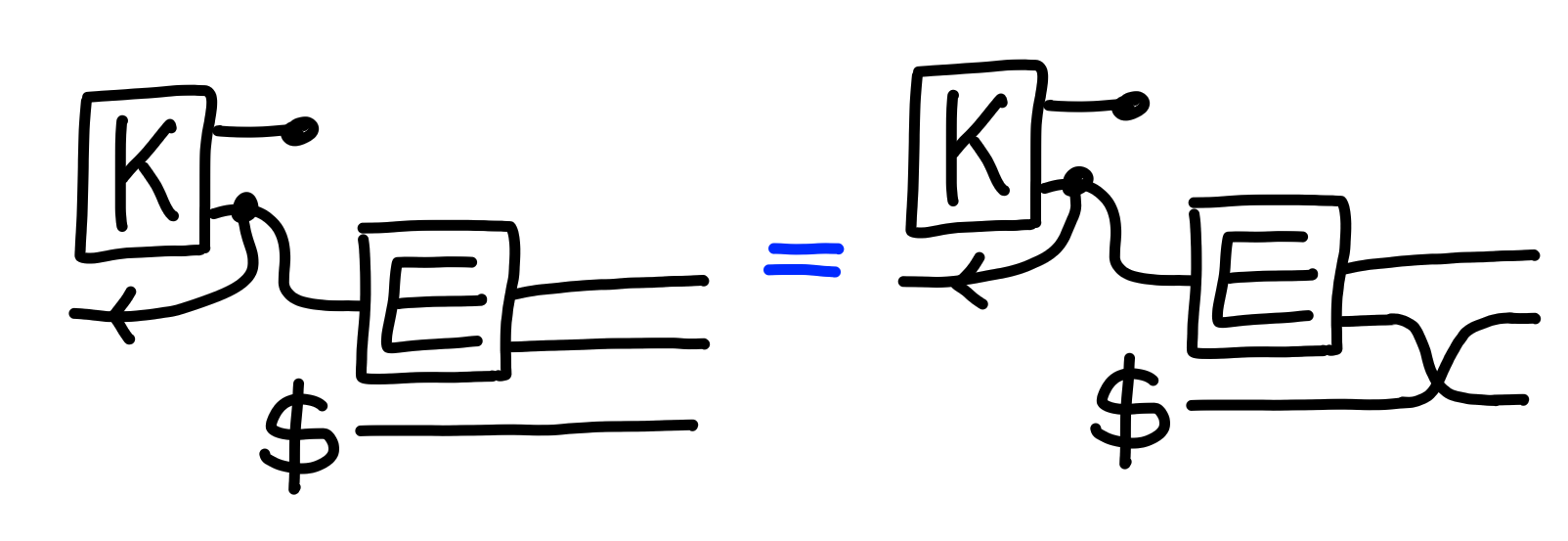

and decapsulating match, or, in other words, that swapping

them doesn’t matter:

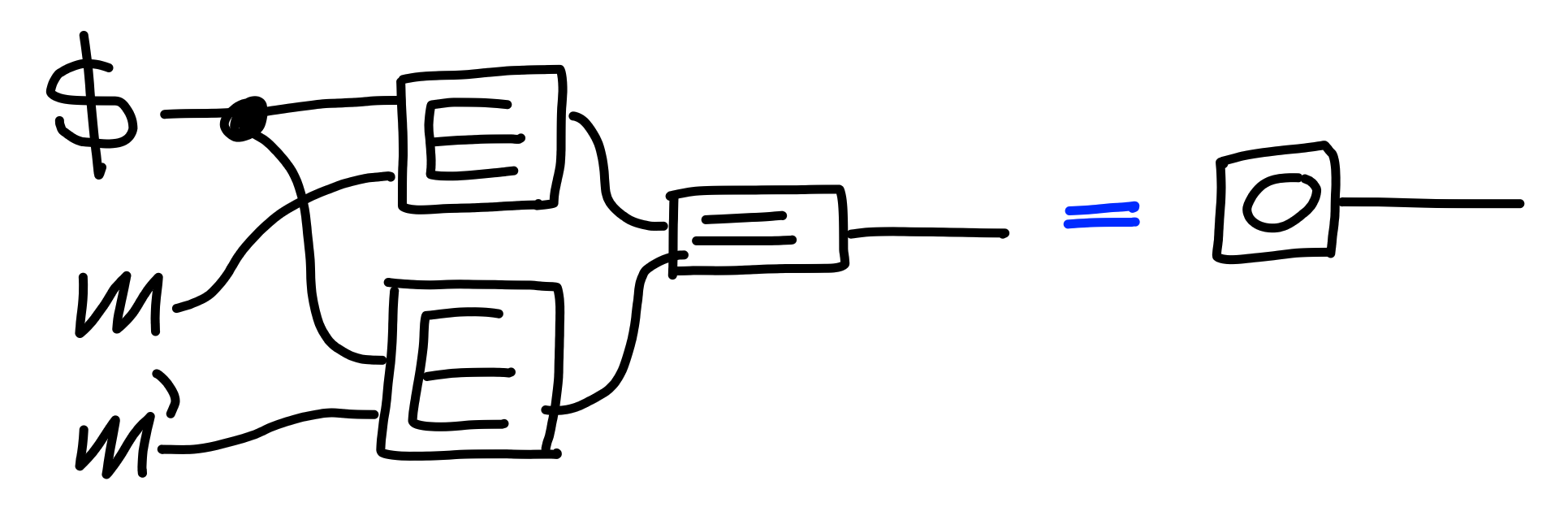

For security, we have a similar notion as that of public key encryption.

Instead of a “left vs right” notion, we instead use one of “real vs random”.

Using a random key instead of the one produced in encapsulation

yields an equivalent process.

This is formally defined in the property $\Pi[\text{KEM-IND}]$:

Public-Key Encryption is a KEM

One obvious way to make a KEM is to generate a random key,

and then encrypt it with a public key encryption scheme:

We can easily check that this satisfies the correctness property,

assuming the underlying public key encryption scheme does:

Furthermore, security is also simple to check:

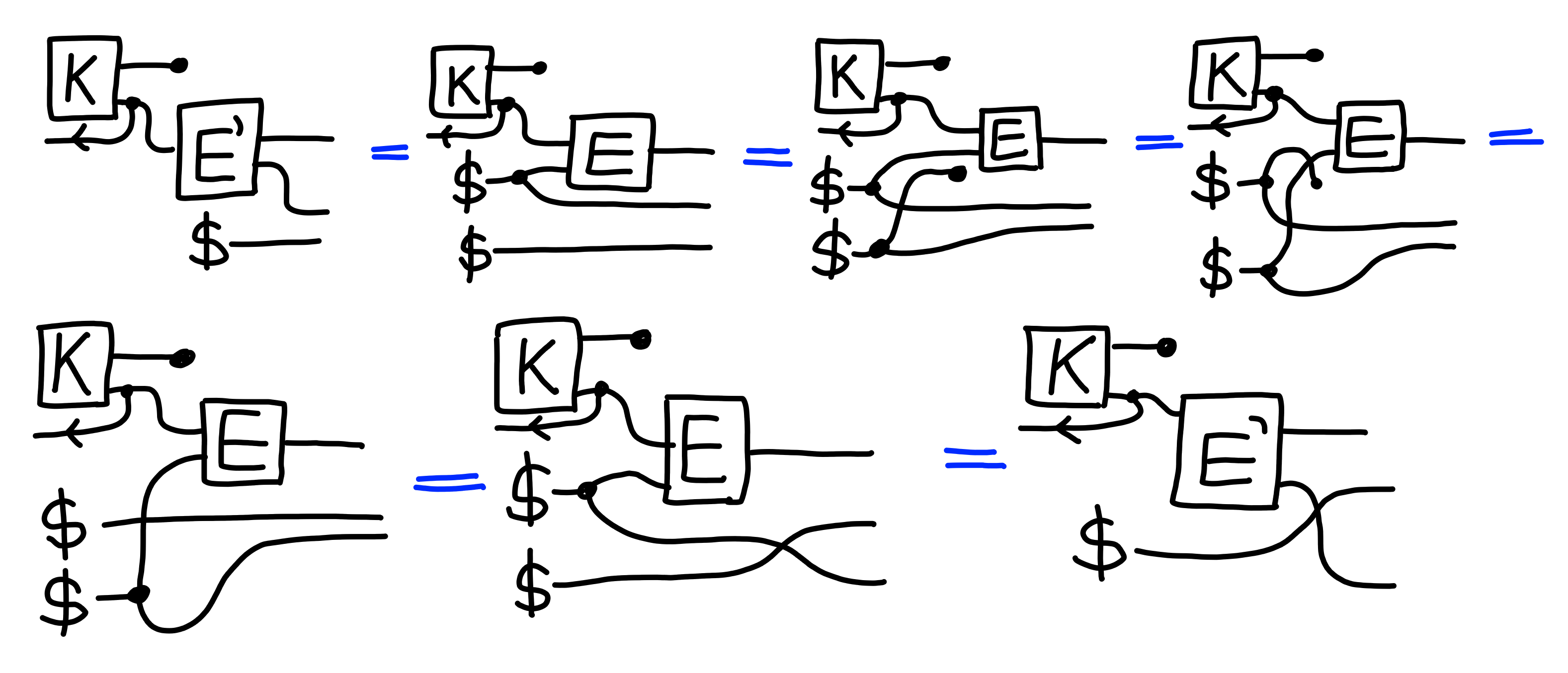

KEM + Encryption = Public Key Encryption

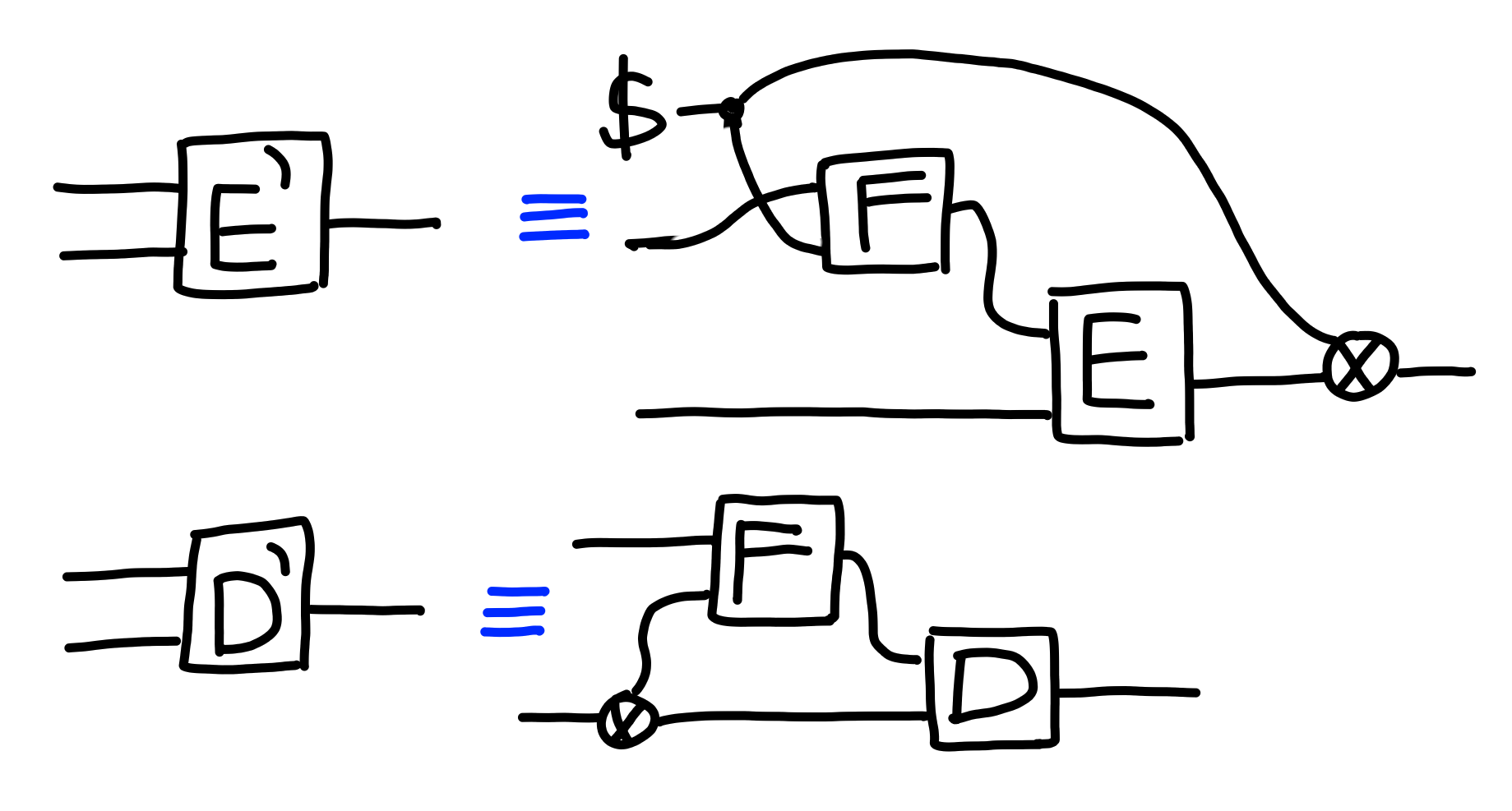

The next thing we show is that one can combine a

KEM and a symmetric encryption scheme,

in order to get a public key encryption scheme.

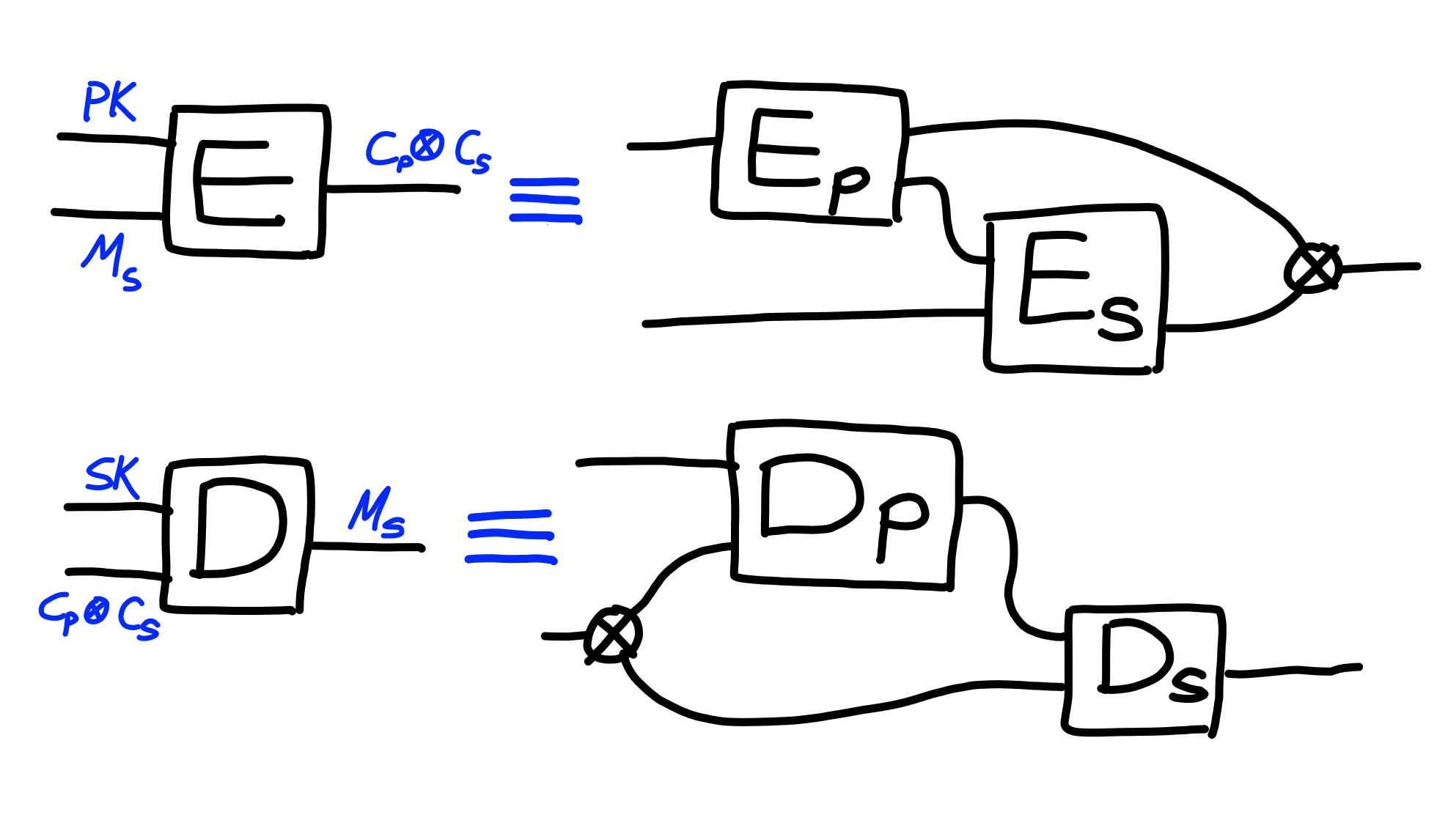

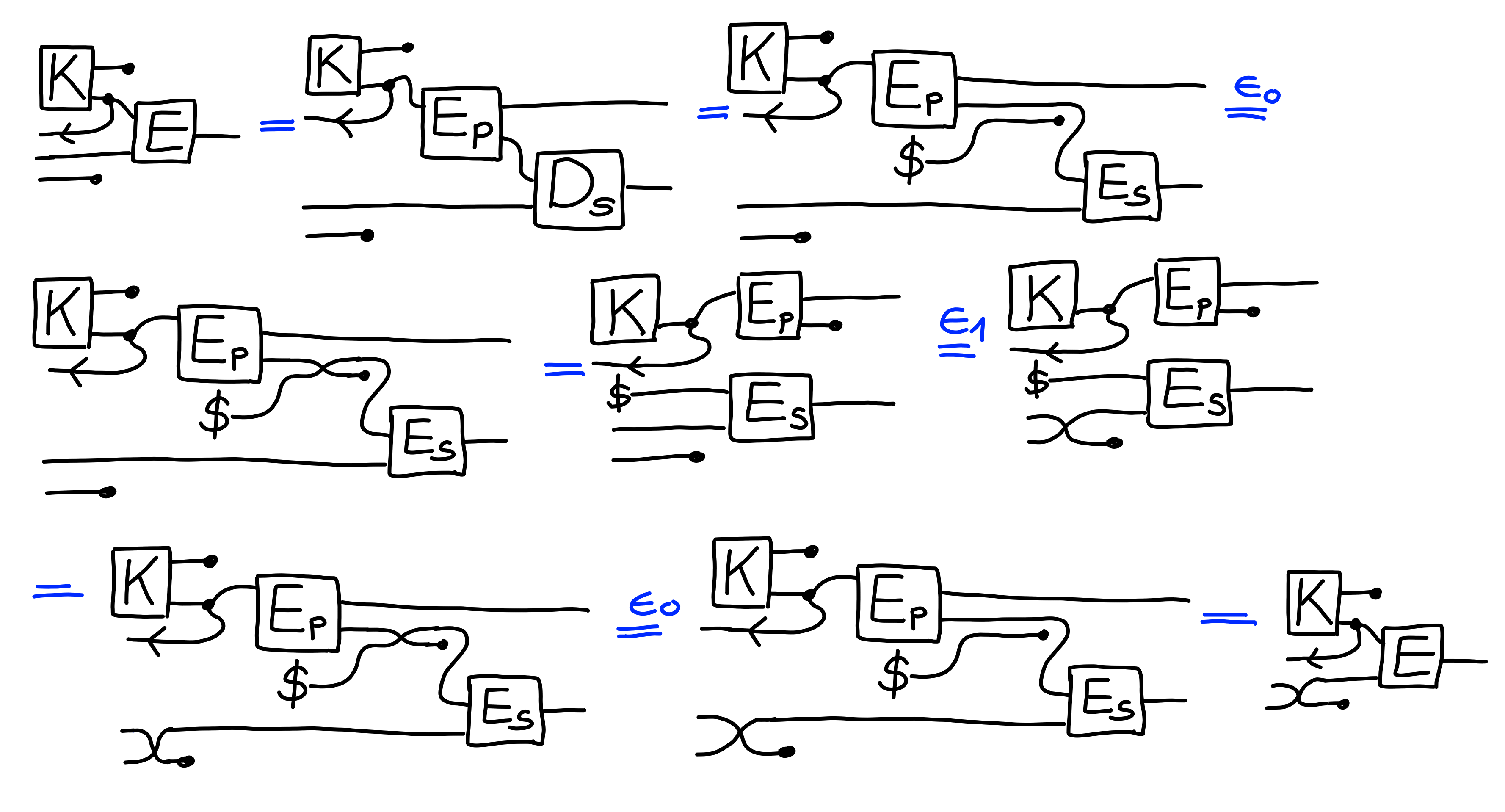

We write $E_p$ and $D_p$ for the kem, and $E_s$ and $D_s$ for the symmetric

encryption scheme, and then define the following PKE scheme:

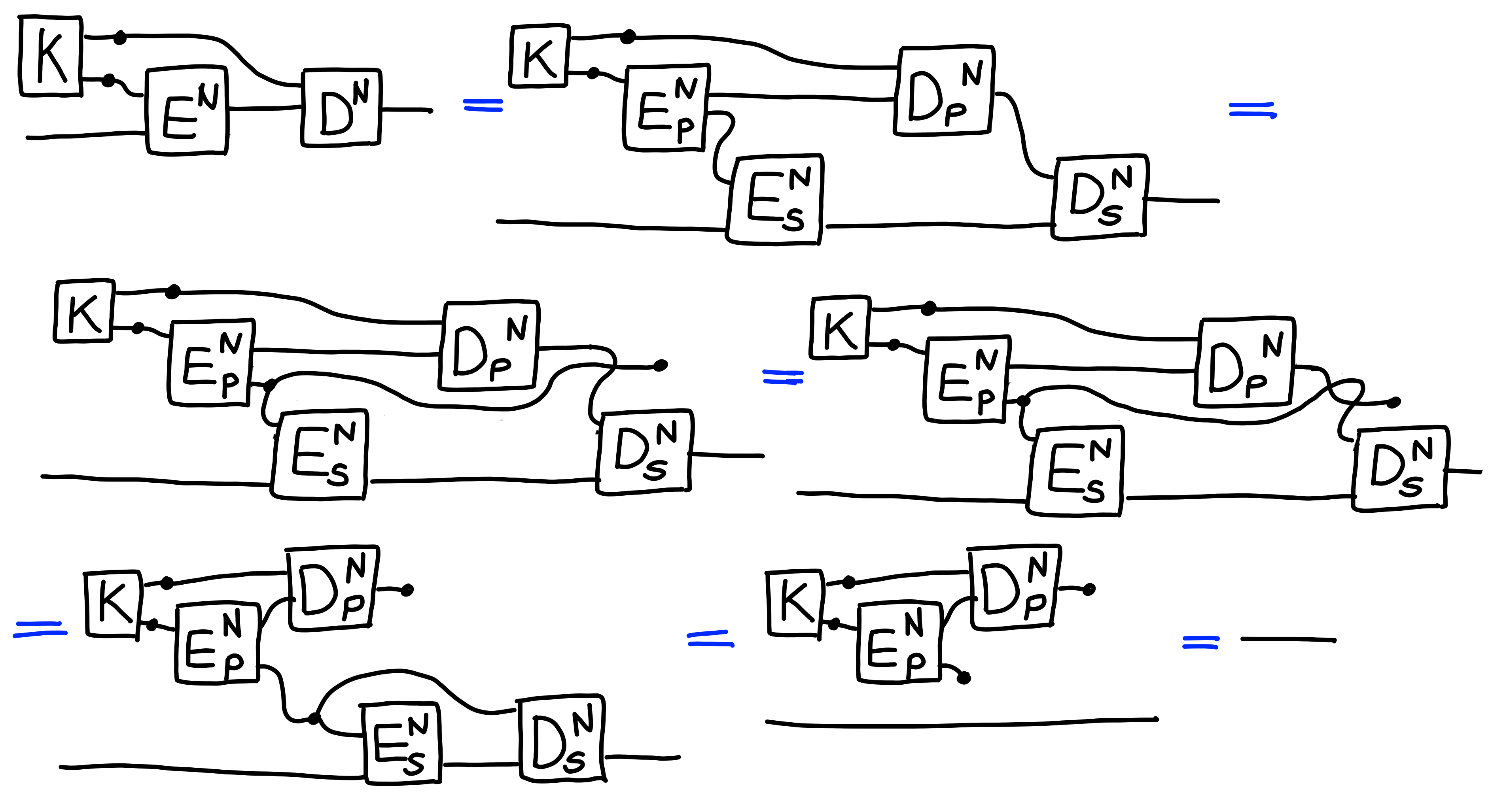

We can check that this scheme is correct, assuming

the underlying KEM and symmetric encryption scheme are:

Next, we prove that this scheme also inherits the security of the underlying primitives it’s made up of:

Claim:

$$

\Pi[\text{KEM-IND}]^2 \otimes \Pi[\text{IND}] \multimap \Pi[\text{PK-IND}]

$$

Proof:

$\blacksquare$

With that, we now have a somewhat simplifies recipe to construct public key encryption: just construct a KEM, and then use any IND-secure encryption scheme, such as a one-time pad.

KEMs from Group Assumptions

In this section, we construct the underlying KEM used in ElGamal encryption. The underlying cryptographic assumption we use is related to the hardness of the discrete logarithm in a finite group, such as the group of points on an Elliptic Curve. This is a very common and practical scheme.

Groups

Before we get to hardness assumptions, we need to define the basic group structure we’ll be working with in this section: i.e. the “cryptographic group”.

A cryptographic group consists of:

- a type of scalars $\mathbb{F}$,

- a type of group elements $\mathbb{G}$,

- a distinguished point $G \in \mathbb{G}$,

- operators $+, \cdot : \mathbb{F}^2 \to \mathbb{F}$,

- an operator $+ : \mathbb{G}^2 \to \mathbb{G}$,

- an operator $* : \mathbb{F} \otimes \mathbb{G} \to \mathbb{G}$.

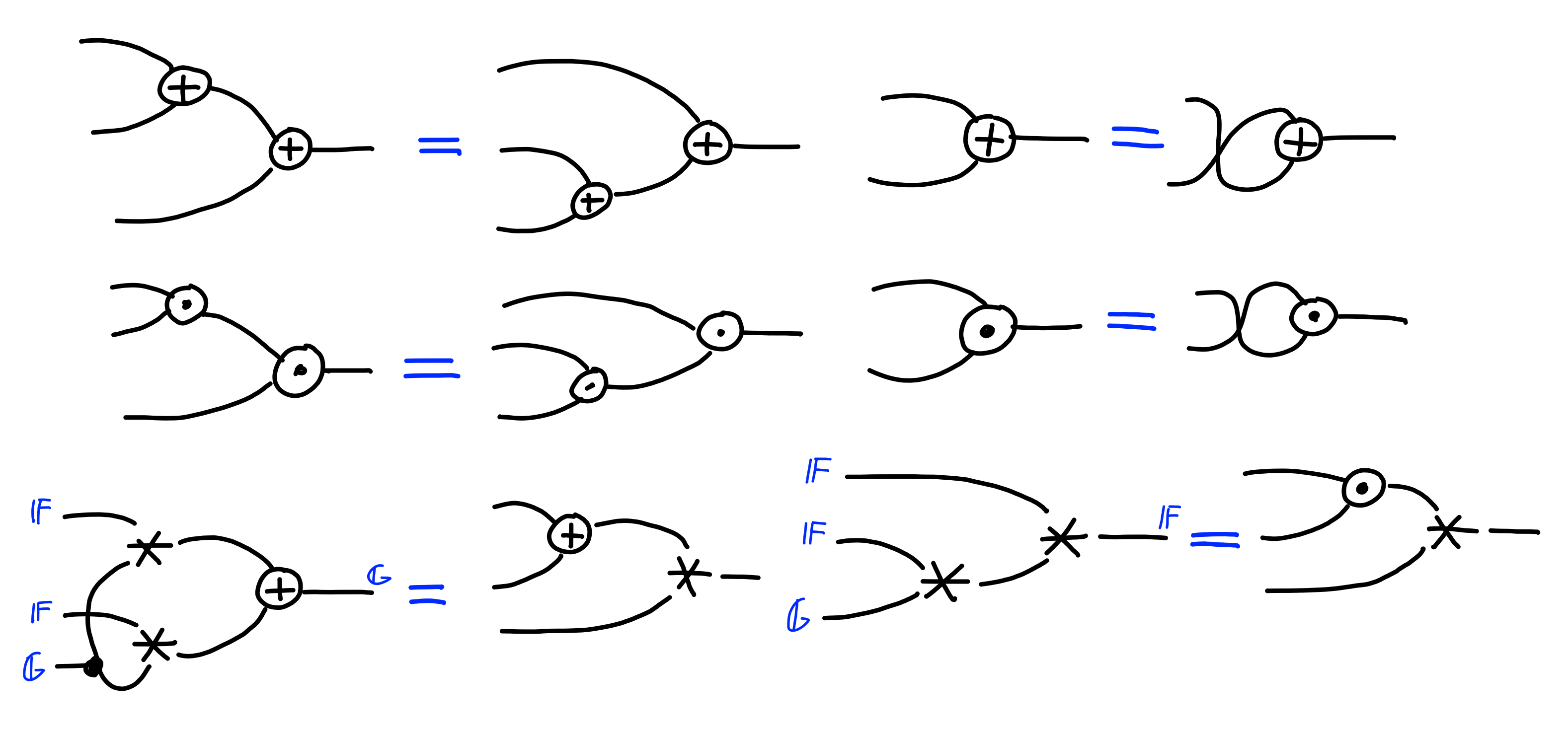

Furthermore, these need to satisfy the following properties:

DLog Assumption

Where things get interesting, from a cryptographic point of view, is when we start adding hardness assumptions on top of these basic operations.

A fundamental hardness assumption is that it’s difficult to compute discrete logarithms in the group. In other words, given a group element, it’s difficult to figure out the scalar element required to reach that element from the generator, via $*$.

Formally, the property $\Pi[\text{DLOG}]$ holds:

CDH Assumption

We’ll be needing a stronger assumption, namely that of the “Computational Diffie Hellman” problem, or “CDH”. This says that given $A = a * G, B = b * G$, it’s difficult to compute $C = a \cdot b * G$.

More formally, the assumption is characterized by the following property,

$\Pi[\text{CDH}]$:

As to why this assumption is useful, the beauty of the synthetic approach is that you can just sort of observe how it gets used, and thus see why it’s useful. In other words, it’s useful cause you can use it.

ElGamal KEM

Next, we construct a KEM whose security will be linked to this assumption.

The secret key will be a scalar in $\mathbb{F}$, the public key a value in $\mathbb{G}$, and the encapsulated key a value in $\mathbb{G}$. We also assume a hash function $H : \mathbb{G} \to K$, mapping group elements into symmetric keys. We’ll see how we model the security of this function later, for now, when looking at correctness, we just need to know that it’s a deterministic function.

The crux of this scheme will come from the fact that: $$ ab * G = a * (b * G) = b * (a * G) $$

We’ll have $a * G$ as our public key, and $b * G$ as our encapsulation, with $H(ab * G)$ as the secret. This allows the holder of $a$ to calculate the secret from the encapsulated value.

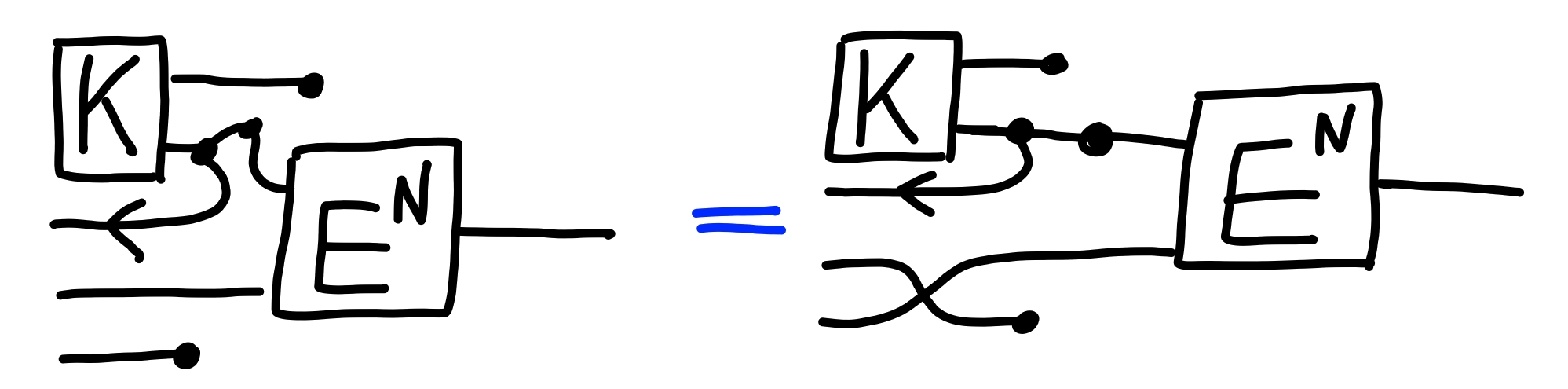

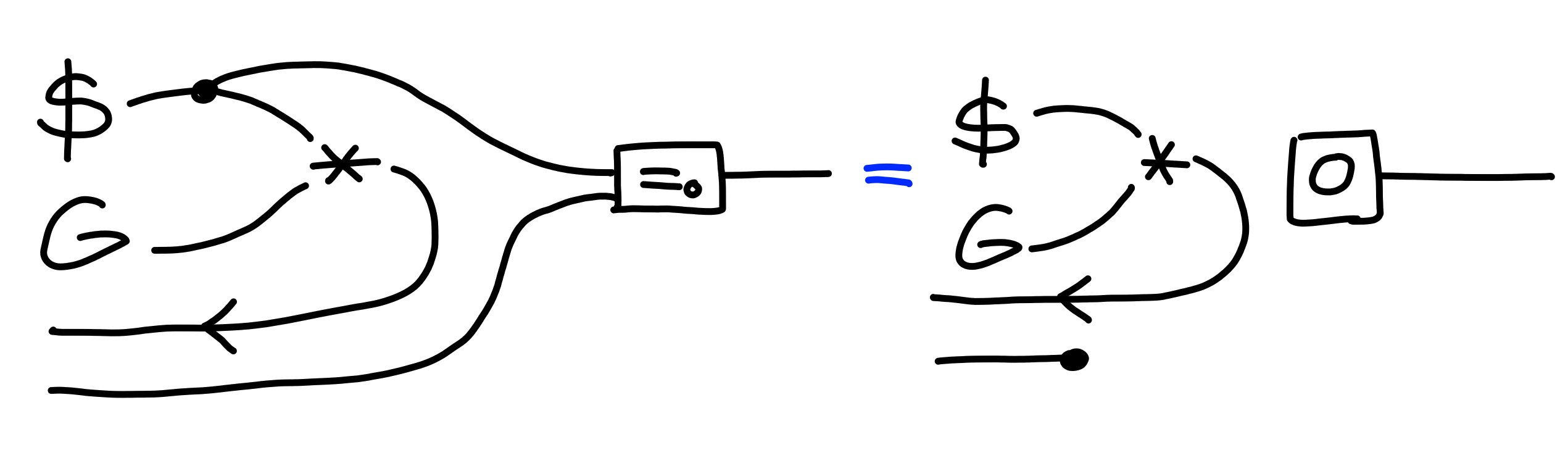

In more detail, let’s define the algorithms for our KEM:

At this point, we can go ahead and check the correctness of this construction:

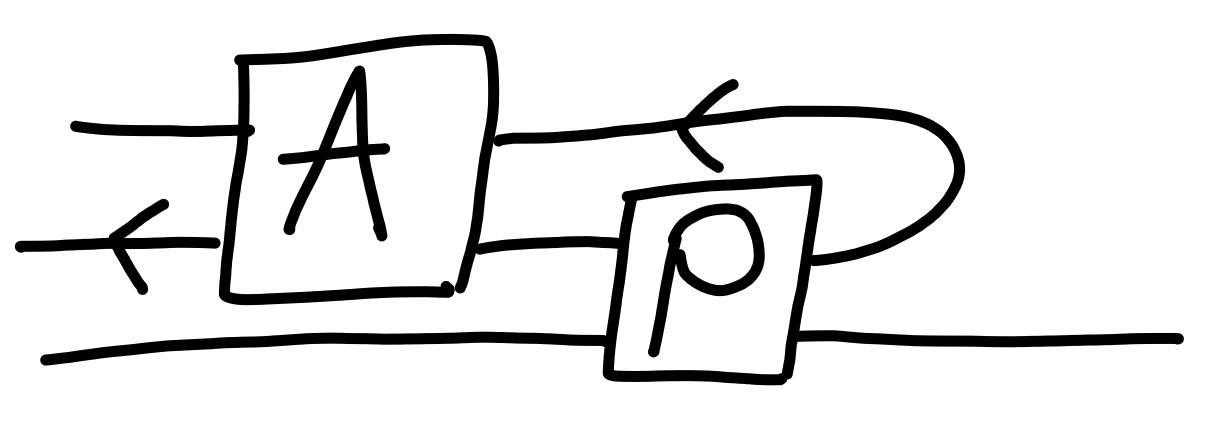

Random-Oracle Model

What we’ll be doing is modelling $H$ as a random function. Just replacing $H$ with $\rho$ isn’t a great model though, since it’s possible to call $H$ in other contexts, and get the same results as one does inside of this KEM, because $H$ is just a deterministic algorithm.

In order to model the ability of “other parts” to also have access to $H$, we will modify our games to also allow queries to $H$.

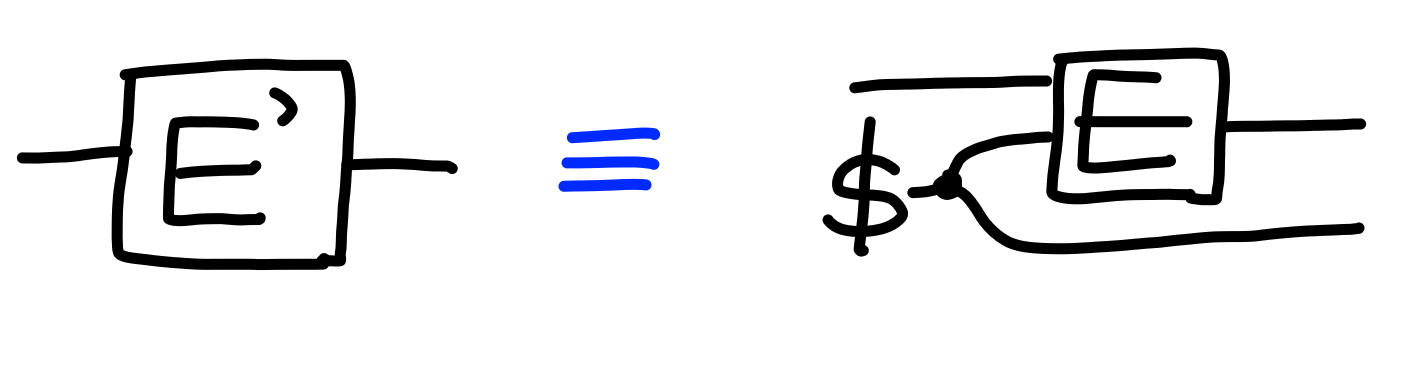

Diagramatically, a process using a hash function $H$ will be modeled as:

This is called the “random oracle model” of security for processes using hash functions.

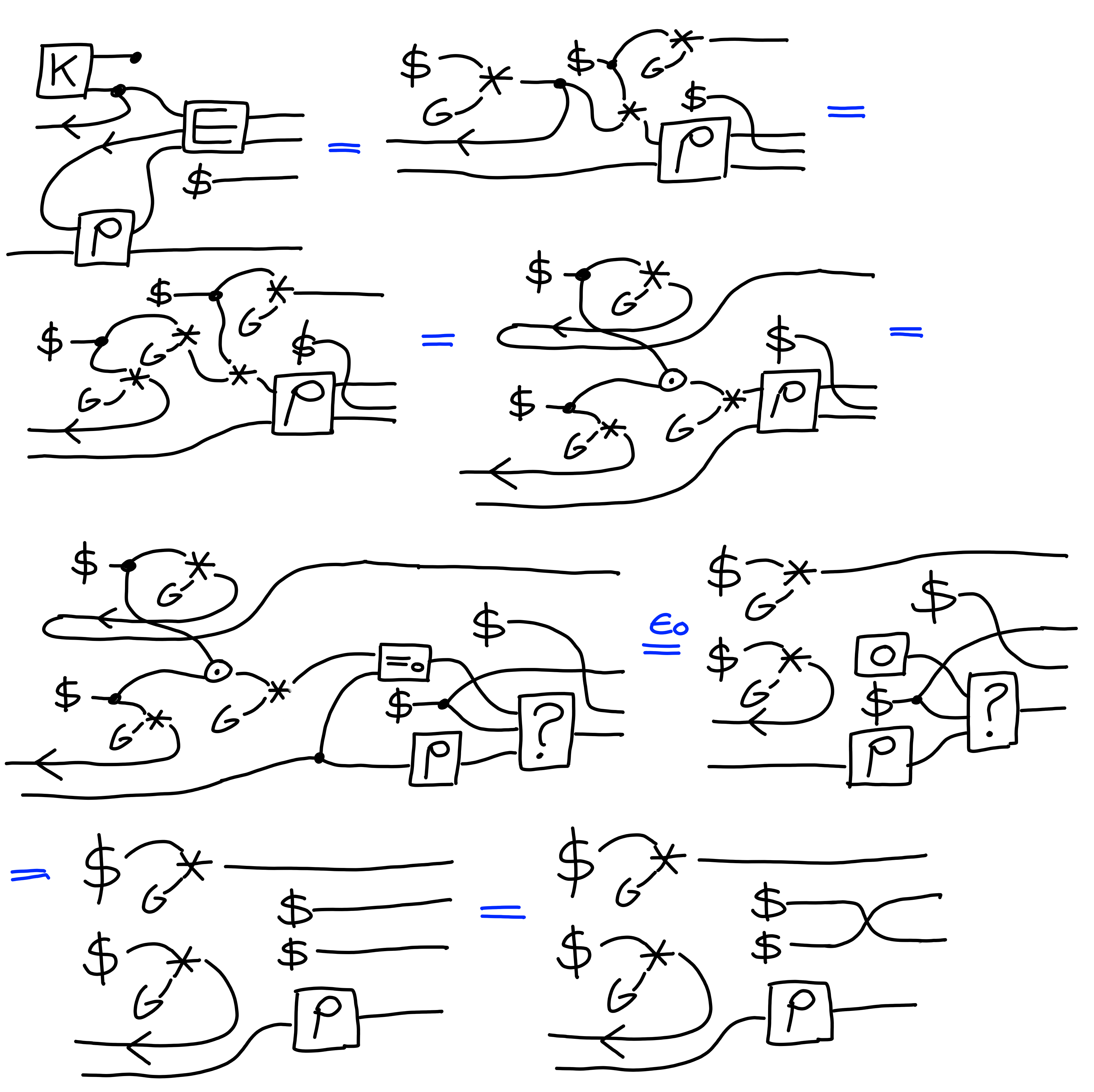

Proving Security

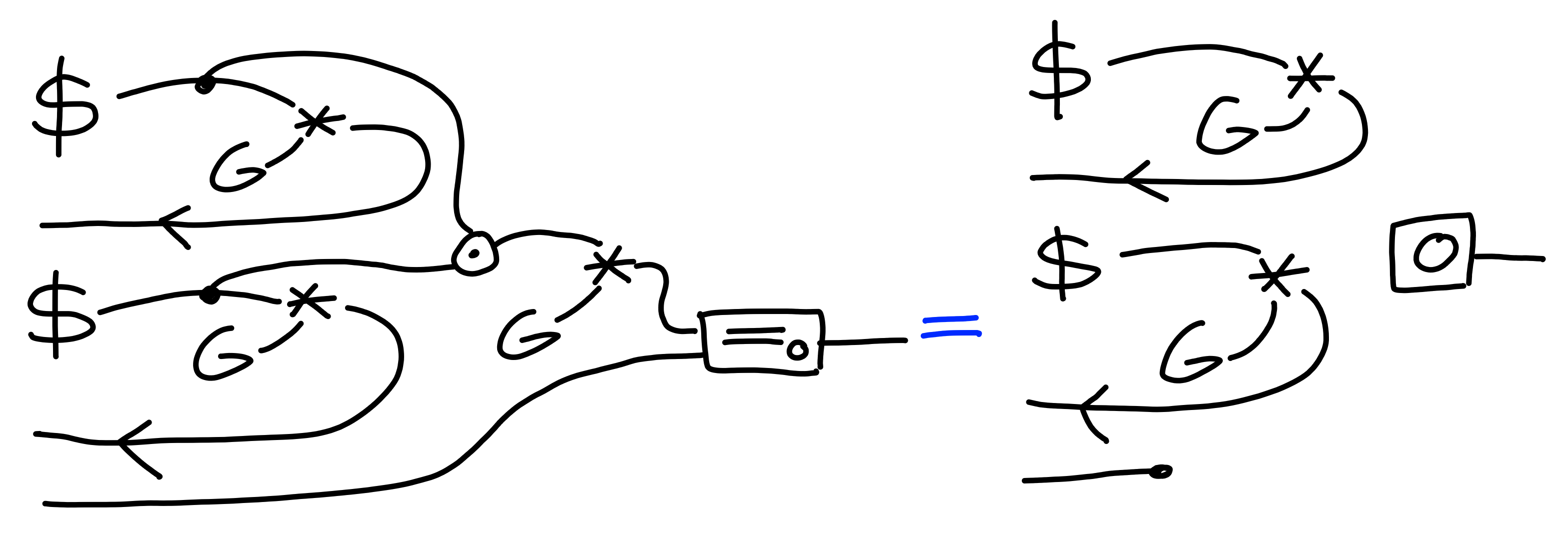

With this in hand, we can prove the security of our group-based KEM in this model.

Claim:

In the random oracle model, it holds that:

$$

\Pi[\text{CDH}]^2 \multimap \Pi[\text{KEM-IND}]

$$

Proof:

$\blacksquare$

Conclusion

Hopefully this post gave you a taste of some of the kinds of arguments this graphical syntax enables. I’ve also restrained myself from trying to give a precise semantics for the string diagrams in this post, mainly because I haven’t yet figured out those semantics, but also because I think the “synthetic” style, where you avoid a concrete semantics, working in a free category, is the best one for most work.

As the post went on, I tried to put more and more weight on the graphical reasoning, as opposed to words, trying to show a bit of the extremes you can get if you really embrace it. Hopefully I didn’t lose you there.

I expect there to be more posts in this style as I flesh out the details, and talk about various minutiae in the formalization.

References

[PZ23] An Introduction to String Diagrams for Computer Scientists