Canetti et al's Paradoxical Encryption Scheme

When proving security, Cryptographers often model hash functions as random oracles, which act like random functions. In practice, hash functions are different from random oracles. The question is: does this difference impact security?

It turns out that it does. In 1998, Ran Canetti, Oded Goldreich, and Shai Halevi constructed an example of an encryption scheme which was secure with random oracles, but insecure if any concrete hash function were to be used. This example shows that, in general, proving that a scheme is secure with random oracles is not enough to show that it’s secure with a real hash function.

I’ll be trying to present this fun little result in a more informal way, leaning on some of the natural intuition we have about how computer programs work, instead of the heavier formalisms used in their paper.

The Ideal of the Random Oracle

A random oracle is not really something that exists: rather, it is a technique we use to reason about security. We model some component of a Cryptographic scheme as a random oracle, and study the security of that scheme with this model. We often say that some scheme is secure “in the random oracle model”, when talking about security proofs made using this technique.

Example: Hybrid Encryption

As an example, let’s consider a scheme using hybrid encryption. We’ll combine a Diffie-Hellman key-exchange, with a symmetric encryption scheme, to create an asymmetric encryption scheme.

The private key will be a scalar $x \in \mathbb{F}_q$, and the associated public key will be the point ${X := x \cdot G \in \mathbb{G}}$.

Encrypting a message can be described with three steps:

- Generate a random key pair $(e, E := e \cdot G)$, and obtain the shared secret ${S := e \cdot X}$.

- Derive a symmetric key $k$ from this secret.

- Encrypt the message $m$ using $k$, to obtain $c$. Join $c$ with $E$ to produce the ciphertext $(E, c)$.

Step 2 is where we bridge points in the group with keys for our symmetric encryption. In practice, this is usually done with a hash function $H : \mathbb{G} \to \mathcal{K}$. A random oracle is used to model how this hash function behaves. The idea is that this function should act like a randomly chosen function. There shouldn’t be any way to predict what the output of the function will be, without actually calling the function.

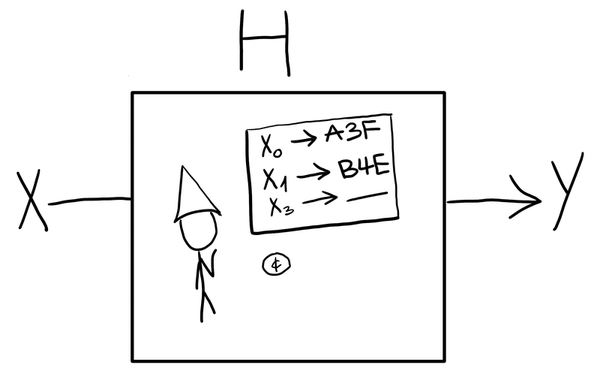

This random oracle is like a gnome in a box generating random outputs for our function. When we give an input to the gnome, it will check if it’s already decided on an output, and generate a random output otherwise.

In practice, we don’t actually need to talk about gnomes when proving the security of schemes. Instead, this book-keeping is managed as part of the game we use to model security.

To illustrate, let’s look at the $\text{IND-CPA}$ security of this hybrid encryption scheme.

We model the security of this encryption scheme as two libraries $\mathcal{L}_0$ and $\mathcal{L}_1$:

$$ \boxed{ \begin{aligned} &\colorbox{#FBCFE8}{\large $\mathcal{L}_{b}$ }\cr \cr &x \xleftarrow{R} \mathbb{F}_q\cr &X := x \cdot G\cr \cr &\underline{\mathtt{Pk()}: \mathbb{G}}\cr &\ \texttt{return } X\cr \cr &\underline{\mathtt{Challenge}(m_0, m_1 : \mathcal{M}): \mathbb{G} \times \mathcal{C}}\cr &\ e \xleftarrow{R} \mathbb{F}_q\cr &\ E := e \cdot G\cr &\ k := H(e \cdot X)\cr &\ c := \text{Enc}(k, m_b)\cr &\ \texttt{return } (E, c)\cr \end{aligned} } $$

The adversary interacts with one of these libraries. If the encryption scheme is secure, then the adversary shouldn’t be able to figure out which of the two libraries it’s interacting with.

This library makes calls to the hash function $H$. In the random oracle model, we model this function by generating random outputs on demand:

$$ \boxed{ \begin{aligned} &\text{outputs}[\cdot] := \bot\cr \cr &\underline{H(P : \mathbb{G}): \mathcal{K}}\cr &\ \texttt{if } \text{outputs}[P] = \bot:\cr &\ \quad \text{outputs}[P] \xleftarrow{R} \mathcal{K}\cr &\ \texttt{return } \text{outputs}[P]\cr \end{aligned} } $$

Every time we need to query the function, we generate a random output, making sure to reuse the output if we’ve already generated it before.

And this is really all there is to random oracles. They’re much easier to work with, because their output has no structure whatsoever, unlike a real hash function. This makes proofs in the random oracle model simpler. In this case, a sketch of the security proof is essentially that the only way to break the scheme would be to somehow gain information about the key $k$. But because we model $H$ as a random oracle, the only way to do that would be to learn $e \cdot X$, since the output is completely unrelated. And being able to learn $e \cdot X$ from $E$ and $X$ is reducable to the Computational Diffie-Hellman (CDH) problem.

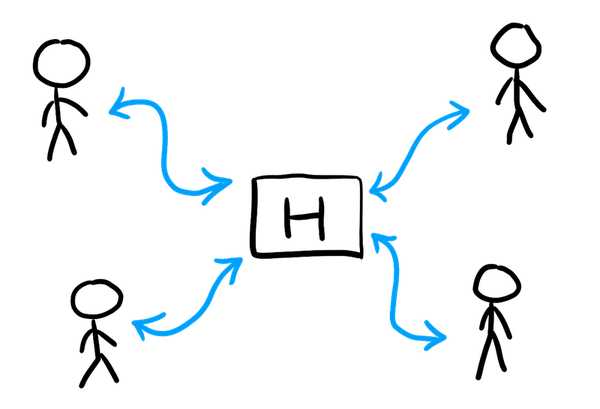

This approach also extends to the case of protocols, where multiple players are interacting, instead of just one adversary interacting with a challenger. In this case, the random oracle is modelled as a common function that all the players have access to. Internally, it still works with the lazy random outputs technique we used here; or with something equivalent.

Hash Functions

In practice, we don’t have random oracles, nor magic gnomes. Instead, we have actual hash functions, like BLAKE3, or SHA256, aut cetera. Do these functions behave like random oracles?

Trivial Differences

There’s one trivial way in which all of these fail to be random oracles, which is that we can pre-compute their outputs. For example, the SHA256 of the empty string is:

e3b0c44298fc1c149afbf4c8996fb92427ae41e4649b934ca495991b7852b855

I can tell that SHA256 is being used, and not a random oracle, simply by querying the random oracle on the empty string. Since the random oracle is initialized at the start of the security game, it won’t already have this output baked in. In all likelihood, I’ll see a different outupt for the empty string.

This stems from a more fundamental issue with modelling the security of hash functions. Because a hash function doesn’t have any dependency on secret inputs, it’s possible for an adversary to have a lot of knowledge about that hash function already “baked in”.

For example, SHA256 necessarily has collisions – two inputs with the same hash – because the output space is smaller than the input space; more pigeons than holes. But, no one knows a collision, nor does anyone know a procedure for efficiently finding one. Nonetheless, there does exist some program which immediately outputs a collision. And, if you tried to model collision resistance as a security game, you’d run into the issue that this preminiscent adversary would win that game, because there’s no secret information involved.

On the other hand, if the hash function were calculated using a secret key, such that calculating the function without the key were difficult, then the adversary would be forced to actually interact with the challenger, actively finding a collision instead of being born knowing that collision.

Another related approach is to use a keyed hash function, but also provide the adversary with the key. We could even integrate this into our hybrid encryption scheme from the previous section. The public key would also include a hashing key to be used with the hash function, when deriving the encryption key from the share Diffie-Hellman secret.

You can abstract this a bit further, by modelling a hash function such as SHA256 as a family of hash functions. SHA256 relies on the following block of constant values:

428a2f98 71374491 b5c0fbcf e9b5dba5

3956c25b 59f111f1 923f82a4 ab1c5ed5

d807aa98 12835b01 243185be 550c7dc3

72be5d74 80deb1fe 9bdc06a7 c19bf174

e49b69c1 efbe4786 0fc19dc6 240ca1cc

2de92c6f 4a7484aa 5cb0a9dc 76f988da

983e5152 a831c66d b00327c8 bf597fc7

c6e00bf3 d5a79147 06ca6351 14292967

27b70a85 2e1b2138 4d2c6dfc 53380d13

650a7354 766a0abb 81c2c92e 92722c85

a2bfe8a1 a81a664b c24b8b70 c76c51a3

d192e819 d6990624 f40e3585 106aa070

19a4c116 1e376c08 2748774c 34b0bcb5

391c0cb3 4ed8aa4a 5b9cca4f 682e6ff3

748f82ee 78a5636f 84c87814 8cc70208

90befffa a4506ceb bef9a3f7 c67178f2

“These words represent the first 32 bits of the fractional parts of the cube roots of the first sixty- four prime numbers.”, as per RFC 6234.

But you could have chosen different values for these constants. So, in some sense, you can think of SHA256 as a family of hash functions, one for each choice of constants. Then you’d model security games involving SHA256 as first involving a public, but random, choice for these parameters, and then using the version of SHA256 with those parameters. This would avoid the trivial issue of adversaries magically knowing collisions, because their knowledge would depend on this choice of parameters.

Some Non-Trivial Differences

SHA256 specifically is actually not a random oracle in a less trivial way. This is because it suffers from Length Extension Attacks.

Essentially, if you know $H(m_0)$, and the length of $m_0$, then you can learn $H(m_0 || m_1)$, for a somewhat specially crafted $m_1$.

Now, this quirk doesn’t violate any kind of collision or preimage property we expect hash functions to have, although it does lead to broken protocols if they naively concatenate variable length inputs.

On the other hand, this behavior is very different from that of a random oracle. With a random oracle, the output is chosen at random, so we aren’t able to predict what the output is going to be on a different message, no matter what the relation is with other messages.

With SHA256, we can predict the output on related messages, thus breaking this unpredictability.

While this quirk breaks the properties of a random oracle, it’s very specific to SHA256 (or hash functions following the Merkle-Damgård paradigm). The question is then: are there hash functions without any such quirk?

Canetti’s Paradox

This is the question Canetti et al. answered, in the negative: no matter which hash function you choose, there will be a “quirk” which lets you distinguish this hash function from a random oracle. In fact, the quirk they found was “this hash function can be implemented by a deterministic computer program”. This is a quirk shared by every hash function we know of, and will ever invent.

Strings are Programs

To understand this quirk, we’ll first have to take a bit of a detour. Let me start with a notion that was controversial 100 years ago, but is pretty much accepted by any programmer nowadays:

You can interpret a string of characters as a program.

If you take a string like foo, bar, or print("hello"),

then you can try and interpret it in your favorite programming

language. You’ll either get a valid program which

does something, or you won’t. That last string,

print("hello") happens to be a valid python program, printing hello.

So, given a string, we might have a valid program. Given this program, we might be able to interpret it as a hash function. For example, the following string:

def hash(x):

return b"0"

is the world’s worst hash function, but it most definitely has the shape of a hash function.

All of this is just to say that given a string $s \in \{0, 1\}^*$, I can interpret that string as a function ${\langle s \rangle : \{0, 1\}^* \to \{0, 1\}^* + \bot}$, potentially outputting $\bot$ if we have an invalid program, or the program doesn’t have the shape of a hash function, etc.

The Quirk

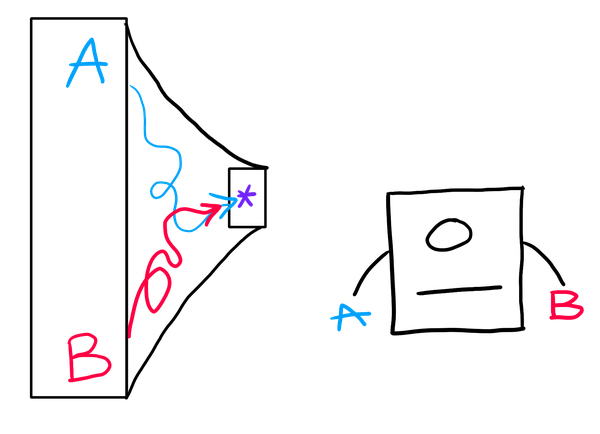

So, let’s say I’m given an oracle as an opaque box $H$. I’m trying to figure out whether or not I have a real random oracle, or whether or not this box is just running some kind of deterministic computer program on each message.

Given a message $m$, I can interpret this message as function $\langle m \rangle$, and then evaluate it on the original message $m$, to get

$$ \langle m \rangle (m) $$

I can then compare this with the result of $H$, checking:

$$ \langle m \rangle(m) \stackrel{?}{=} H(m) $$

And here’s the magic part. If $H$ is actually a computer program, then there’s a special message $m_*$ which will make this check pass. All I have to do is pass in the source code for $H$. If $m_*$ is the source code for the program implementing $H$, then $\langle m_* \rangle$ is the same function as $H$, and so the check will pass, both sides being equal to $H(m_*)$

On the other hand, if $H$ is a genuine random oracle, there’s no way to consistently make the check pass, because the output is genuinely unpredictable, and has no relation with whatever is happening with the $\langle m \rangle(m)$ part.

So, no matter which hash function $H$ you use to try and implement a random oracle, you will always run into this quirk, because your hash function is implemented by a computer program. And this quirk is also easy to find, because if you’re using $H$ in your program, it’s because you have access to code implementing $H$.

A broken Encryption Scheme

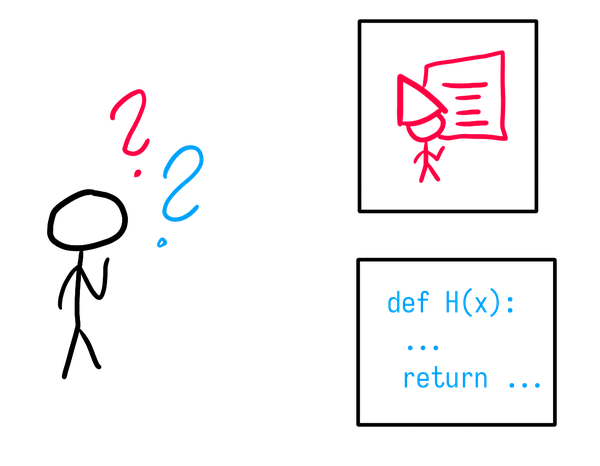

So, there’s a quirk which lets us tell the difference between a concrete hash function and random oracle, no matter the hash function: does that actually mean that secure schemes using random oracles become broken if we use a concrete hash function?

Sometimes, yes.

Let’s start with the hybrid encryption scheme we had earlier:

$$ \boxed{ \begin{aligned} &\underline{\texttt{Enc}(m : \mathcal{M})}: \mathcal{C}\cr &\ e \xleftarrow{R} \mathbb{F}_q\cr &\ E := e \cdot G\cr &\ k := H(e \cdot X)\cr &\ c := \texttt{SymmetricEnc}(k, m_b)\cr &\ \texttt{return } (E, c)\cr \end{aligned} } $$

Since this scheme makes use of a hash function $H$, we can try and modify this scheme so that it gets broken because of the quirk. We want to end up with a scheme which is secure for random oracles, but broken for any concrete hash function.

What’s the easiest way to make a scheme broken? Leak the private key! We can modify the scheme to simply leak the private key along with the ciphertext, using our quirk:

$$ \boxed{ \begin{aligned} &\underline{\texttt{Enc'}(m : \mathcal{M})}: \mathcal{C}'\cr &\ e \xleftarrow{R} \mathbb{F}_q\cr &\ E := e \cdot G\cr &\ k := H(e \cdot X)\cr &\ c := \texttt{SymmetricEnc}(k, m_b)\cr &\ \colorbox{palegreen}{$\text{leak} :=x \texttt{ if } \langle m \rangle(m) = H(m)\texttt{ else } \bot$}\cr &\ \texttt{return } (E, c, \colorbox{palegreen}{leak})\cr \end{aligned} } $$

We interpret the message as a hash function, and evaluate it at $m$, comparing it with the result of $H$. If $H$ is a random oracle, then finding a message which makes this check pass is exceedingly difficult, and so nothing will actually get leaked. On the other hand, if $H$ is a real hash function, then we can encrypt the source code of $H$, and have our encryption scheme spit out the secret key.

Thus, this scheme provides a nice counter-example, which shows that there are schemes secure in the random oracle model, but insecure when instantiated with a real hash function.

Lessons?

While this is a nice theoretical result, the scheme we’ve created is a bit silly, for two reasons:

- In practice, a scheme isn’t going to have an explicit “trapdoor” which automatically leaks its private key if some condition is met.

- The quirk that $\langle m \rangle(m) = H(M)$ seems quite artificial as well.

Now, while these points are true, I think we shouldn’t be too quick to dismiss this result. In general, counter-examples in Cryptography seem quite contrived at a first glance, but they can illustrate more subtle issues.

There are many examples of vulnerabilities where a small amount of information leakage can be exploited to mount a more complete attack. Take the example of Bleichenbacher’s Attack, or Padding Oracles. So while the trapdoor on our contrived scheme is very obvious, it’s possible that a concrete scheme suffers from smaller and more subtle information leakage because of the difference between a random oracle and a concrete hash function.

This brings us to the second point. The quirk we’ve noticed exploits a fundamental, but somewhat trivial difference between hash functions and random oracles: hash functions can be implemented with a program. We used this difference to create a scheme which is only secure with random oracles. But, it’s not clear if this property actually matters for security in “realistic” schemes. For example, Pseudo-Random Functions (PRF) can also implemented with a program, but are believed to be as unpredictable as a random oracle, provided you don’t know the secret key used when evaluated them. On the other hand, it’s possible that there are more subtle differences between random oracles and hash functions, and that these differences do result in exploitable vulnerabilities in actual schemes.

By using a very obvious difference, and a obvious clear trapdoor, we make our counter-example crystal clear. But even though our counter-example is far removed from concrete schemes, there could still be subtler differences and trapdoors which might exist with more realistic schemes.

Conclusion

At this point, one question should be: can proofs in the random oracle model be trusted? I think I want to say yes to this question. Obviously, we shouldn’t take the random oracle model as a trivial assumption, and if a proof can avoid relying on it, that’s all for the better. On the other hand, there are now many proofs relying on this model, and the only major flaw I know of resulting from the use of this model is perhaps the presence of Length Extension Attacks, and other similar issues with message concatenation.

There are assumptions that we have to rely on in Cryptography, like the hardness of certain problems, and maybe the random oracle model is just one of the assumptions we’ll have to concede.

It may also be possible to provider a weaker form of the random oracle model which is still strong enough to be useful for proofs, but weak enough that we can use concrete hash functions in order to implement it.

Maybe you’ll be the person who discovers these models 8^).