Introducing Nuntius

Recently, I made a toy E2E encrypted messanger, called Nuntius. I had fun tinkering on it, and thought that some of the cryptography involved would be fun to explain.

Application Overview

I’ve called Nuntius an E2E encrypted messenger. You connect to a server, requesting to chat with a certain person. When that person connects to the server in turn, you can send messages to each other. Calling this a messenger is a bit generous. It’s more of a session based chat application, like IRC. I’d expect a messenger to support multiple users, and asynchronous messaging, but I’ll get to this point later.

For a more concrete overview, let’s see what CLI commands are actually used to start chatting. Using the kong library for command line option parsing, I’ve generated useful help screens for free, including this one:

→ ./nuntius --help

Usage: nuntius <command>

Flags:

-h, --help Show context-sensitive help.

--database=STRING Path to local database.

Commands:

generate

Generate a new identity pair.

identity

Fetch the current identity.

add-friend <name> <pub>

Add a new friend

server [<port>]

Start a server.

chat <url> <name>

Chat with a friend.

Run "nuntius <command> --help" for more information on a command.

The first step is generating a key pair, using generate:

→ ./nuntius generate --database .test/1.db

nuntiusの公開鍵3176cb883a9efd0e6002ed539dc6c03a504d982a47945e30fb0ac06e7dbc3b94

This prints out your public identity. This defines who you are according to this system. You share this identity with people you want to chat with, allowing them to contact you. This command saves a corresponding private key in a local file. This is actually an SQLite database, whose path is configurable, as shown by the command I’ve used. If you don’t specify a path, then this file goes into your home directory.

If you ever forget what your identity key was, you can use

identity to fetch it from the database.

Since identity keys are used to identify the people you want to chat with, you can associate identity keys with more familiar names. When your friend John tells you what his Nuntius identity is, you can save that in your local database, so that you can chat with John later.

This is done with the add-friend command:

→ ./nuntius add-friend John nuntiusの公開鍵3176cb883a9efd0e6002ed539dc6c03a504d982a47945e30fb0ac06e7dbc3b94

Then, you can chat with your friend John using Nuntius:

→ ./nuntius chat http://localhost:1234 John --database .test/1.db

You can start sending messages when John connects to the same server on his end. This requires a server to connect to. The server forwards messages between the two of you, but can’t read their content at all. I’ve used a local server path, but you can replace this with any other path. I’ve simply chosen this one, because it’s the default path for the server command.

This command runs a Nuntius server:

→ ./nuntius server 4000

This takes a port as an argument, but will use 1234 as a default port

otherwise.

So, that’s just about it. The big limitation here is that both users need to be connected at the same time, to the same server. The CLI interface is also a bit clunkier than a GUI interface. I wanted to focus on the E2E encryption aspect, which is why I took these shortcuts.

To implement the encryption, I basically used bits and pieces of how Signal works. They conveniently have documentation for some of their abstracted protocols, which I shamelessly reimplemented.

Implementation

I used Go for the implementation this time, mainly for a change of pace. I also didn’t implement any primitives from scratch, only protocol-level constructions. This meant exploring Go’s ecosystem of cryptography libraries, which was pretty fun.

I might want to extend this little experiment into a more useful GUI app, and I’m thinking of trying things out in Rust for that. The goal would be to learn how to do things myself, not to rival with any other system.

The rough idea of how the application works is simple. Two users know each other by their identity key, so they can perform an exchange, deriving a shared secret. They then use that secret to encrypt their communication. Signal throws a twist in both the exchange, and the encryption. They use a more complicated exchange system, to reduce the security load on the long-lived identity keys. They also use a ratcheting mechanism for encryption, so that the encryption key is refreshed with new exchanges.

Let’s get into how both of these work.

Key Exchange

If your long term identity keys are Diffie Hellman keys, like X25519 keys, then you can both derive a shared secret, knowing only the other’s public key. There’s no problem with this, per se. This exchange is secure. One issue is that the identity key is completely load-bearing. At each exchange, you need to rely on it, without being able to rekey the exchange with new information. Each exchange will also generate the same key, which isn’t desirable either.

X3DH

Signal’s solution to this is a protocol called X3DH. Instead of using your friend’s identity key to derive a shared secrete, you instead use three keys of theirs. I believe this is where the name comes from.

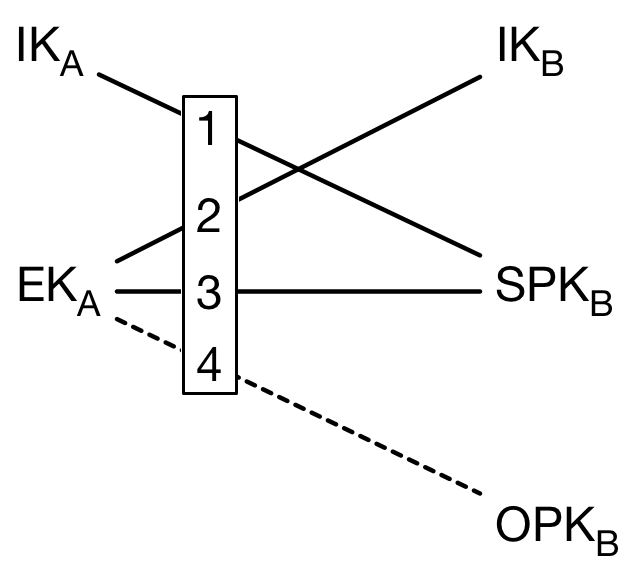

To perform the exchange, you use your identity key, $IK_A$, as well as a a new ephemeral key $EK_A$. You use your friend’s long term key $\text{IK}_B$, as well as a signed prekey $\text{SPK}_B$, and an ephemeral key $\text{OPK}_B$. The last two keys are fetched from the server, and only the signed pre-key can be verifiably attributed to your friend, through its signature.

Using these keys, you perform an exchange like this:

This gives you 4 shared secrets, which you can then strain through a KDF to get a symmetric key. You can use this key to start encrypting data, or to start a more complicated ratcheting process, as we’ll see later.

In all honesty, I don’t fully understand the reasoning behind all of the keys involved here. I suspect that other variations of the scheme can provide the same guarantees. There are a few important ideas that I think I do understand.

The first is that the exchange uses ephemeral information, so that leakage of identity keys in the future doesn’t allow compromising past conversations. Using a prekey also reduces load on the main identity key, and signing it prevents an adversary from substituting their own one.

I think there might be something going on with deniability, which might be why $\text{OPK}_B$ isn’t signed. I’m not entirely certain if this is the reasoning though.

Setting up your keys

As I’ve just mentioned, $\text{SPK}_B$ and $\text{OPK}_B$ need to be retrieved from the server, in order to start your exchange. The first one is accompanied by a signature, and is intended to be used multiple times. The second one is only intended to be used once.

Your friend needs to have supplied these to the server in advance. In the application, I handle these by resupplying keys as necessary when chatting, since you have to connect to the server anyways. I don’t refresh $\text{SPK}$, although doing so periodically would be a good idea. The main refresh is in supplying the server with new bundles of $\text{OPK}$. The idea is that you generate, say, 100 of these ephemeral keys, and sign the whole package before sending it off to the server. The server can verify that you generated these keys, by checking the signature. This signature is only valid for the entire bundle, and doesn’t work for individual keys. Each time an exchange is done with you, you burn one of these one time keys, never using it again. If the supply of one time keys on the server dwindles, you can refresh it by sending a new bundle.

All of this management is transparent to how the application works, but is important from an implementor’s perspective.

Signing and Exchange

If you look at the keys we use for exchanges, you’ll notice that we use $\text{IK}$ both for signing a pre-key, and for doing a Diffie-Hellman exchange. We need a dual purpose key, which most protocols don’t provide. Signal recommends using an X25519 key, which makes exchange easy, and then converting it to an Ed25519 key for signing.

I found it easier, at least in Go’s ecosystem, to do the opposite. I use an Ed25519 key for identity, which makes it easy to sign, and then do the conversion to X25519 when an exchange happens.

I won’t go over exactly how this work, because Filippo Valsorda has a great blog post going over this. I could also make use of his equally great package edwards25519, in order to implement the following functions:

func (priv IdentityPriv) toExchange() ExchangePriv {

hash := sha512.New()

hash.Write(priv[:32])

digest := hash.Sum(nil)

return digest[:curve25519.ScalarSize]

}

func (pub IdentityPub) toExchange() (ExchangePub, error) {

p := new(edwards25519.Point)

_, err := p.SetBytes(pub)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return p.BytesMontgomery(), nil

}

Starting a Session

Signal is intended to be used in an asynchronous setting. You connect to the server and give it the necessary keys. Then you can start and maintain new sessions with other users. For the synchronous sessions, I had to adapt things a little bit.

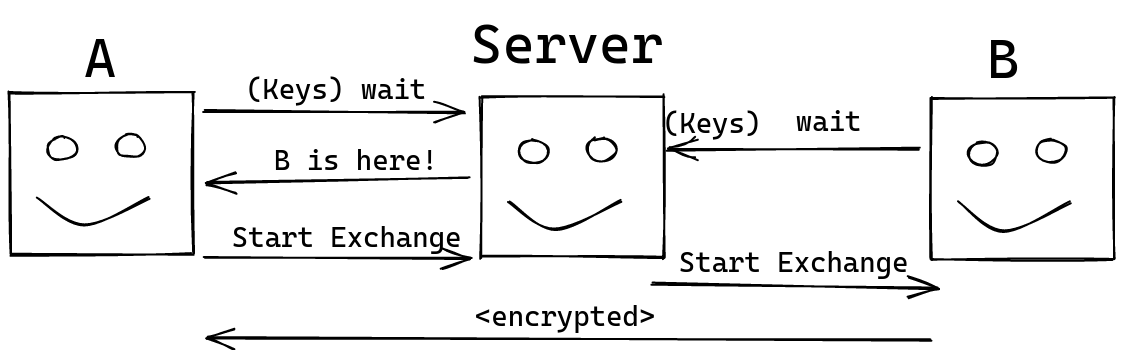

In Signal’s model, you start messaging someone by performing an exchange, and then sending a message to Signal’s server. The server dutifully stores it until the receiver is ready. I wanted to avoid a store-and-forward architecture here. Instead, I wait to establish a synchronous connection before forwarding messages.

This leads to a three way exchange:

First, you connect to the server, and wait. You take advantage of this connection to send new one-time key bundles, if necessary. Then, when your friend connects, you now have a synchronous channel with them. The server notifies you of this, and sends you the necessary information to perform an exchange. You do this, and send out a message to your friend, including your ephemeral exchange key, so they can do their side of the exchange. From there on, you now have an encrypted channel you can use, starting from the symmetric key you’ve derived.

Ratcheting

So, we have a symmetric key, and we can start encrypting data. Instead of using this key to encrypt every message we send, we’re going to make a new key for each message. This reduces load on the key we’ve created, and requires active participation in order to compromise the conversation.

We do this by setting up a ratchet. The idea is that we can easily move the ratchet forward, but not backwards. We use the ratchet to derive new message keys from previous keys. We can also perform new key exchanges, and use that to ratchet our keys forward as well.

Signal calls this ratchet system, the Double Ratchet. Once again, I’m not sure of the naming. I like to think that is because you have a standard ratchet to derive new message keys, but also a second layer using new exchanges to move things forward.

Chains

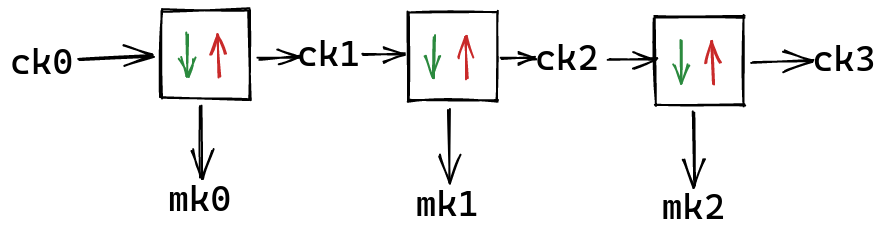

The basic idea of a single ratchet is that each time you want to encrypt a new message, you send your encryption key into a one way function, producing a new encryption key, and a one time key to use with that message. You can then use this new encryption key to produce a key for the message after that, and so on:

You create this chain where you produce new encryption keys, and spit out one time encryption keys for your message keys. Going forward along the chain is easy, but going backwards is exceedingly difficult.

The suggestion for this particular part of the ratchet is to use an HMAC with SHA-256, and your encryption key, called a “Chain Key” in this context, to key the hash:

func kdfChainKey(ck chainKey) (chainKey, MessageKey, error) {

hash := hmac.New(sha256.New, ck)

_, err := hash.Write([]byte{0})

if err != nil {

return nil, nil, err

}

ck = chainKey(hash.Sum(nil))

hash.Reset()

_, err = hash.Write([]byte{1})

if err != nil {

return nil, nil, err

}

mk := MessageKey(hash.Sum(nil))

return ck, mk, nil

}

Of course, other kinds of KDFs could be used. For example, you could use BLAKE3. You would simply use its KDF twice, with different contexts for the new chain and message key.

Diffie-Hellman Ping Pong

We know how to create an encryption chain to send messages starting from a chain key. The next step is to use new Diffie-Hellman exchanges in order to create new chains in a ratcheted way.

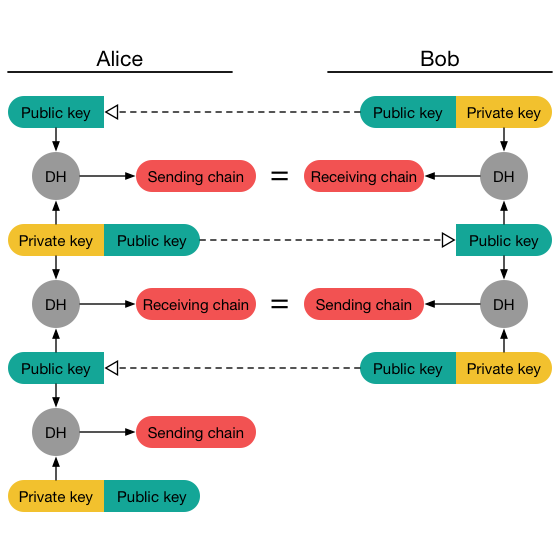

After starting an exchange, we have our partner’s signed prekey available. We can generate a new key pair, and perform an exchange in order to get a new chain key. Then we send our new public key along with our messages encrypted with this chain. Our partner will be able to recreate our chain by mirroring our exchange. They then create a new ephemeral key pair, in order to start an exchange for their sending chain, and so on:

(image courtesy of Signal)

There’s a simple trick to remember how this works. When you send messages, you always create a new chain that your partner doesn’t have a mirror of yet. It’s only when they receive your new public key that they can mirror your sending chain, and decrypt your messages. Because of this, you always do two exchanges once the protocol is running. The first one matches the sending chain that you didn’t have with a receiving, and the second creates an unmatched sending chain.

Basically, your sending chain is always unmatched.

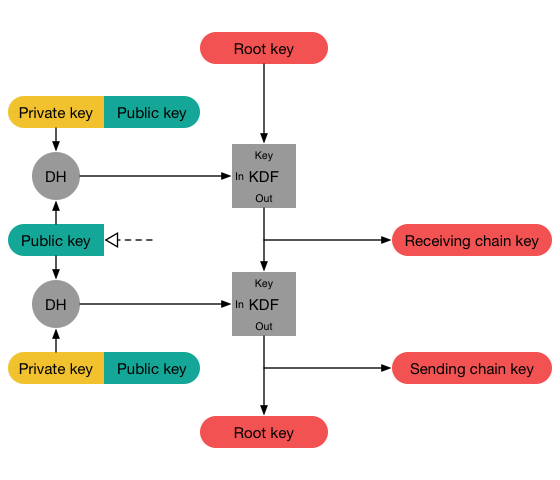

Now, you don’t just generate new chains from scratch. Rather, you use these exchange inputs to ratchet up new chains from previous chains, like this:

(image courtesy of Signal)

You use the exchange to derive not just a new chain key, but also a new root key. This is what creates a “double ratchet”, because you have the ratcheting inside of each chain you create, but also a ratcheting process to derive new chains, guided by asymmetric exchanges.

For this ratchet, the suggested choice is doing HKDF with SHA-256, using your root key as a salt, a context for your application, and the shared secret as key material. You then read out two keys worth of data from this hasher:

func kdfRootKey(rk rootKey, dhOut exchangedSecret) (rootKey, chainKey, error) {

reader := hkdf.New(sha256.New, dhOut, rk, kdfRootKeyInfo)

rootKey := rootKey(make([]byte, rootKeySize))

chainKey := chainKey(make([]byte, chainKeySize))

_, err := io.ReadFull(reader, rootKey)

if err != nil {

return nil, nil, err

}

_, err = io.ReadFull(reader, chainKey)

if err != nil {

return nil, nil, err

}

return rootKey, chainKey, nil

}

An alternate choice, once again illustrating BLAKE3, would be to do a keyed hash of the the exchanged secret, using the root key, and deriving two new keys with its KDF, each time using a different context.

This was more of a colorful overview than a technical one. I’d recommend reading Signal’s Double Ratchet article which explains all of this in sufficient detail to implement.

Limitations

I’ve promised to tell you about the limitations of this application exactly twice so far. In fact, I’ve already told you about them twice, teasing you about their full extent. I’m teasing you a third time right now.

The limitations are there because I wanted to focus on the E2E encryption aspects, mainly implementing X3DH and the Double Ratchet. Signal’s protocols are fundamentally designed around asynchronous communication, and implementing that to its fullest extent would have been a lot more work on things I didn’t feel like focusing on for this project.

Session Based

The main limitation of this CLI tool is that it’s fundamentally session based. You and your friend need to be connected to the same server at the same time, and chatting with each other. You can’t maintain multiple conversations at the same time, besides just opening multiple versions of Nuntius in different terminals, each of which creates a new connection to the server.

A full-blown messanging app would require talking to multiple people in a convenient interface, as well as being able to send messages when a person is offline, having them delivered later.

It would also be nice to have support for messaging people in a group. Id est, group messages. I think Signal does this by actually setting up $N - 1$ 2-way communication channels between each pair of members in the group. There’s also other potential solutions, like MLS, although the Euro competition has gotten much more attention recently.

Lost Messages

The chain structure allows you to keep around old message keys, in case you receive messages out of order. If each message also includes its number, you can match it up with the right key.

I haven’t implemented anything like this.

Why? I didn’t feel like it.

If this were a real app, this would something you’d want. With asynchronous messages, out-of-order delivery becomes lot more likely. With the very synchronous model I’d explicitly downgraded to, this reordering shouldn’t really happen, and would crash the session quickly, allowing both users to just restart it, since they’re already online.

No Contact Discovery

The system I’ve made also identifies users directly with their identity keys, which is a cheap cop-out to avoid dealing with the complicated problem of associating cryptographic identities with real people.

Nuntius basically tells you to go solve the problem yourself, and figure out what identities your friends have, by asking them. Once you know what identity John has for Nuntius, you can save it with the CLI.

A tangentially related limitation is that there’s no support at all for multiple devices, although in theory if you were to copy your local database from one machine to another, things should just work.

Limited Interface

There’s also the fundamental limitation of using a CLI tool instead of a full blown GUI app. I actually do like the idea of making a pretty GUI along with all of the expected features, but this would be a small exercise in cryptography, a medium exercise in desiging application protocols, and a large exercise in making GUIs.

Conclusion

In summary, I made a CLI tool for session based E2E encrypted messaging. I had a lot of fun implementing the cryptographic protocols. I dare say that I actually understand how the Double Ratchet works. I dare not say that I understand why X3DH is the way it is. Perhaps it’s better that my little toy isn’t very intuitive, or easy to use. That way, people won’t use it.

Use Signal :).