Tychonoff's Theorem and Zorn's Lemma

Tychonoff’s theorem proves that the product (even infinite) of compact spaces is also compact. The proof makes judicious use of Zorn’s lemma. In fact, it uses it so well, that I gained an appreciation for how fun the lemma can be.

In this post, we’ll be going over the notion of product space and compact space, building up to the final result.

I think that the final proof makes elegant use of a powerful tool: Zorn’s lemma. This use is so elegant, in fact, that as soon as I first read the proof, I felt compelled to write a blog post exposing the proof, and trying to describe its elegance to others.

All the proofs are inspired by, and sometimes even taken from, Munkres [1], which is the standard introductory text on Topology. I won’t be going over the basics of Topological spaces and continuous functions here, nor will I be exposing all of the details around product and compact spaces, so I recommend this book if you’d like to see these fundamentals, or learn more about Topology.

Compactness

The first notion we need to develop is that of a Compact space. In some sense, a Compact space is analogous to the closed interval $[0, 1] \subseteq \mathbb{R}$. An interval like this has an uncountable number of points, but is still “small” in some sense: we can’t keep squeezing stuff into it.

Formally:

A space $X$ is Compact precisely when any collection of open sets $\{U_\alpha\}$ that cover $X$, (i.e. $\bigcup_\alpha U_\alpha = X$), a finite sub-collection $U_1, \ldots, U_n$ suffices to cover $X$.

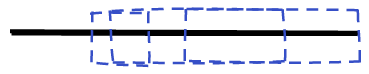

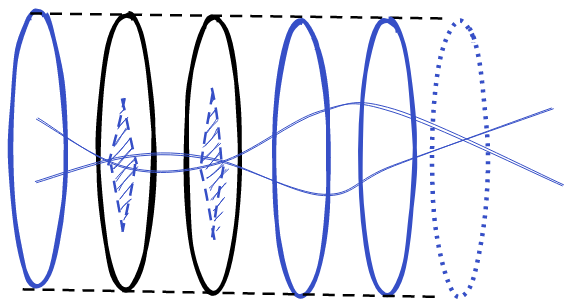

The intuition here goes back to the closed interval. We could try and cover in such a way that no finite sub-cover can exist. For example, by making smaller and smaller advances towards one side of the interval:

The problem is that we never reach the other side, which is included in our interval. So this fails to cover the entire interval. If we had the half open interval $(0, 1]$ instead, then this attempt would work. In some sense, openness makes things not compact, because you can inch towards some point that you reach “in the limit”, but that you miss at every single step. With a closed interval, you need to actually reach every point to cover the interval, not just in a limiting way.

Finite Intersection Property

An opposite, but equivalent formulation of compactness can be given in terms of closed sets and intersections.

First, a definition:

A collection of subsets $\mathcal{A}$ has the Finite Intersection Property (FIP, for short) precisely when any finite intersection of sets in this collection is non-empty.

Theorem: A space $X$ is Compact $\iff$ for any collection of closed sets $\mathcal{C}$ satisfying the FIP, the intersection of this collection is non-empty.

Proof:

This is an exercise in rewriting definitions.

Mathematically, for a space $X$ to be compact, we need:

$$ \begin{aligned} &\forall \{U_\alpha\},\ U_\alpha \text{ open}, \ \bigcup_{\alpha} U_\alpha = X \ .\quad \exists \alpha_1, \ldots \alpha_n . \quad \bigcup_{i = 1}^n U_{\alpha_i} = X \cr &\forall \{U_\alpha\},\ U_\alpha \text{ open}, \ X - \bigcup_{\alpha} U_\alpha = \emptyset \ .\quad \exists \alpha_1, \ldots \alpha_n . \quad X - \bigcup_{i = 1}^n U_{\alpha_i} = \emptyset \cr &\forall \{U_\alpha\},\ U_\alpha \text{ open}, \ \bigcap_{\alpha}(X - U_\alpha) = \emptyset \ .\quad \exists \alpha_1, \ldots \alpha_n . \quad \bigcap_{i=1}^n(X - U_{\alpha_i}) = \emptyset \cr &\forall \{C_\alpha\},\ C_\alpha \text{ closed}, \ \bigcap_{\alpha} C_\alpha = \emptyset \ .\quad \exists \alpha_1, \ldots \alpha_n . \quad \bigcap_{i=1}^nC_{\alpha_i} = \emptyset \cr &\forall \{C_\alpha\},\ C_\alpha \text{ closed}.\quad \bigcap_{\alpha} C_\alpha = \emptyset \implies \exists \alpha_1, \ldots \alpha_n . \quad \bigcap_{i=1}^nC_{\alpha_i} = \emptyset \cr &\forall \{C_\alpha\},\ C_\alpha \text{ closed}.\quad \nexists \alpha_1, \ldots \alpha_n. \ \bigcap_{i=1}^nC_{\alpha_i} = \emptyset \implies \bigcap_{\alpha} C_\alpha \neq \emptyset \cr &\forall \{C_\alpha\},\ C_\alpha \text{ closed}, \ \nexists \alpha_1, \ldots \alpha_n \ \bigcap_{i=1}^nC_{\alpha_i} = \emptyset. \quad \bigcap_{\alpha} C_\alpha \neq \emptyset \cr \end{aligned} $$

All of these are equivalent, and the last one says that for every collection of closed subsets in which no finite intersection is empty, the intersection of the collection is also not empty.

This is precisely the statement we wanted to show as equivalent to compactness.

$\square$

Back to our example of a closed interval of the real line, instead of having a growing open cover that can’t keep growing forever without missing an endpoint, we now have receding closed sets, which must have a common region:

Products

The next notion we need to develop is that of a product space.

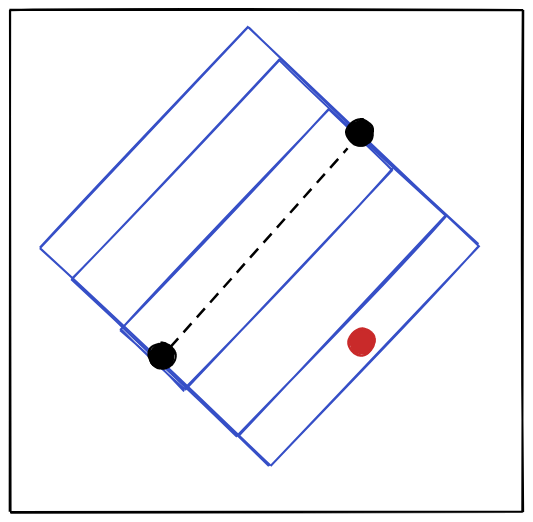

As a motivating example, take our closed interval $[0, 1]$, and consider the set $[0, 1]^2$, whose elements are pairs $(x, y)$ with $x, y \in [0, 1]$:

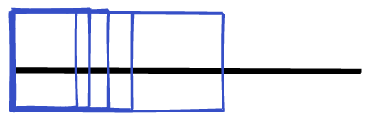

If we have two open sets $U, V \subseteq [0, 1]$, then the product:

$$ U \times V := \{(x, y) \ |\ x \in X, y \in V\} $$

is also open:

This collection is only a basis for this topology.

More generally, set is open precisely when every point contains such a product set:

Finite Products

We can go ahead an provide a formal definition of this construction, for finite products.

Given Topological spaces $X$ and $Y$, the cartesian product $X \times Y$ can be endowed with a topology, whose basis consists of products $U \times V$, with $U$ open in $X$, and $V$ open in $Y$.

The standard projections:

$$ \begin{aligned} \pi_1 : X \times Y \to X \cr \pi_2 : X \times Y \to Y \end{aligned} $$

can be shown to be continuous. This is because:

$$ \begin{aligned} \pi_1^{-1}(U) = U \times Y \cr \pi_2^{-1}(V) = X \times V \cr \end{aligned} $$

In fact, these slices $\pi^{-1}_i(U)$ form a sub-basis: finite intersections of these slices form a basis for this topology.

With this in mind, one way of looking at the product topology is as the simplest way to to make the projections $\pi_1$ and $\pi_2$ continuous. For the projections to be continuous, all of the slices need to be open. Having declared these slices to be open, the product topology emerges freely using the axioms of a topological space.

Extending to the infinite case

We’ve just seen how the topology can be defined in terms of slices $\pi_i^{-1}(U)$ as a sub-basis. This characterization extends naturally to the case where we have an arbitrary collection $\{X_\alpha\}$ of spaces, and consider the infinite product $\prod_\alpha X_\alpha$.

The elements of this set are dependent functions $(\alpha : \Alpha) \to X_\alpha$ for some indexing set $\Alpha$.

We have a set function $\pi_\alpha : \prod_\alpha X_\alpha \to X_\alpha$. And we can define the slices $$ \{\pi_\alpha^{-1}(U) \ | \ X_\alpha \supseteq U \text{ open}\} $$

as our sub-basis.

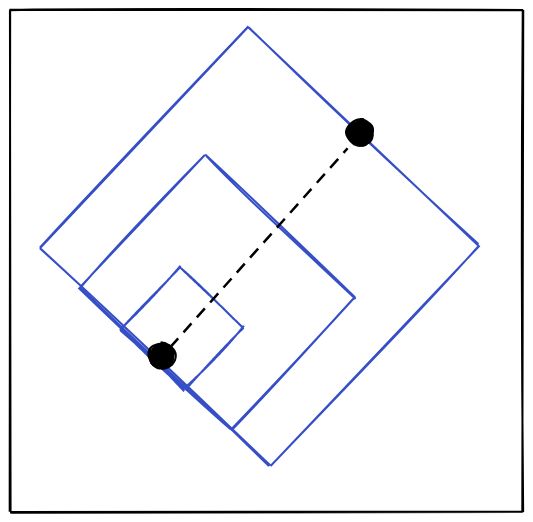

This means that finite intersections of these slices form our basis. But a finite intersection of slices can be more precisely described as a product $\prod_\alpha U_\alpha$ with $U_\alpha$ open in $X_\alpha$, and $U_\alpha = X_\alpha$, for all but finitely many $\alpha$.

Formally, the product topology is defined by taking these special products as our basis. In the case of a finite product, the “$U_\alpha = X_\alpha$ almost everywhere” disappears, since it’s not possible to violate this condition, taking a finite product.

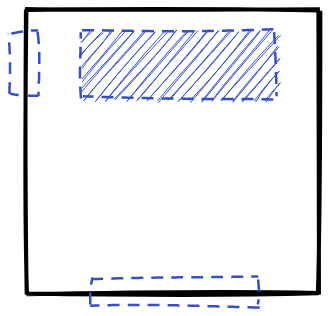

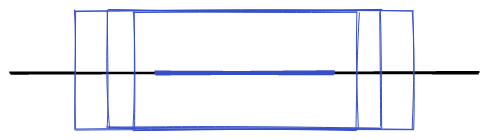

Another way of looking at the infinite product of spaces is by arranging the spaces one after the other as a big cake. The points in this space are then paths through each layer. We can choose a finite number of slices, restricting the paths in that layer, but the other layers remain unconstrained:

Tychonoff’s Theorem

We’ve seen the notion of a compactness, and product spaces. A natural question to ask is whether these properties are compatible:

Given a collection $\{X_\alpha\}$ of compact spaces, is the product $\prod_{\alpha} X_\alpha$ also a compact space?

Tychnoff’s theorem answers this with a definitive yes.

A rough idea, and a problem

It’s more convenient to use the finite intersection version of compactness here. Given a collection $\mathcal{A}$ of closed subsets of our product space, with the finite intersection property, we need to find a point in the intersection $\bigcap \mathcal{A}$.

One idea is to try finding this point component by component, using that fact that each part of our product space is already known to be compact.

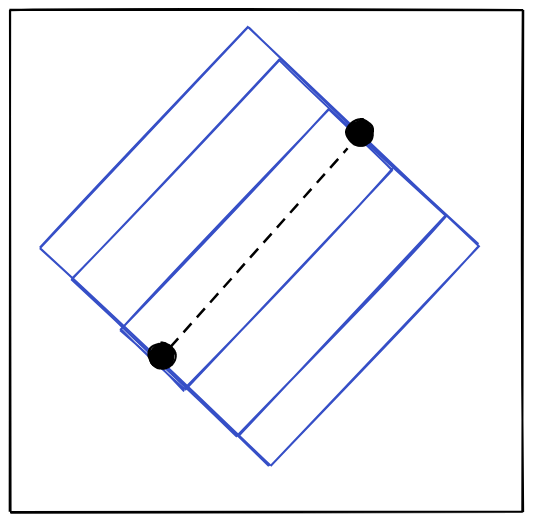

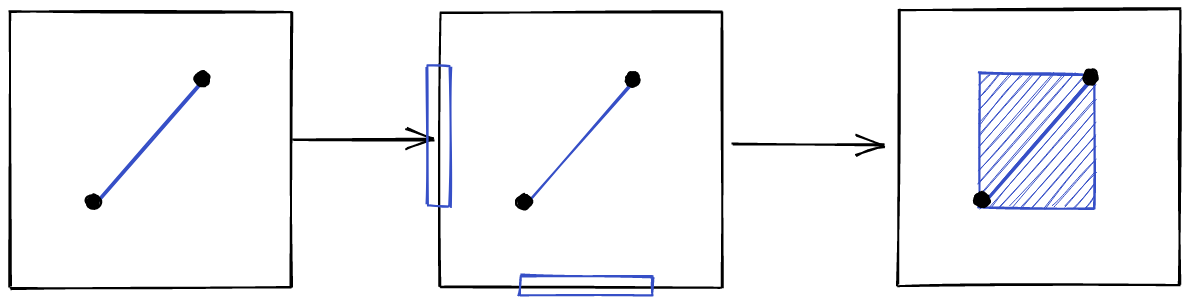

Concretely, consider the product $[0, 1] \times [0, 1]$. Let $a = (\frac{1}{3}, \frac{1}{3})$ and $b = (\frac{2}{3}, \frac{2}{3})$. Our collection $\mathcal{A}$ consists of rectangles centered along the segment $ab$:

This has the finite intersection property. This is because for any two rectangles centered on this line, the smaller one will always be contained in the larger one. It then follows, by induction, that the intersection of any number of these rectangles is also in the collection, and thus non-empty.

In fact, we can see the final intersection of this collection. It is the segment $ab$ itself:

If we project each rectangle down to one of the intervals, we get a nested set of closed intervals, eventually reaching $[\frac{1}{3}, \frac{2}{3}]$:

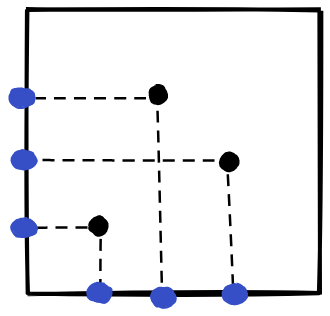

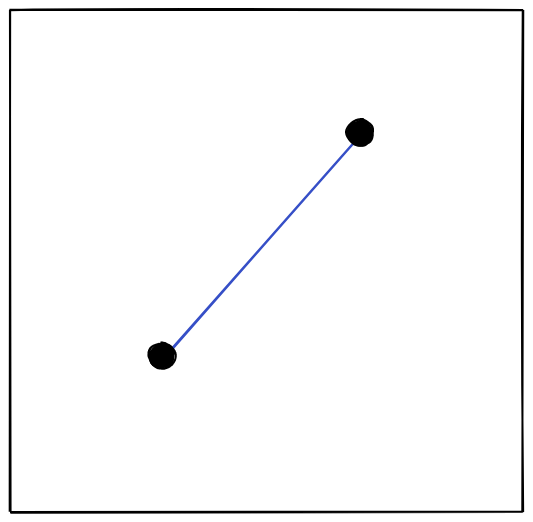

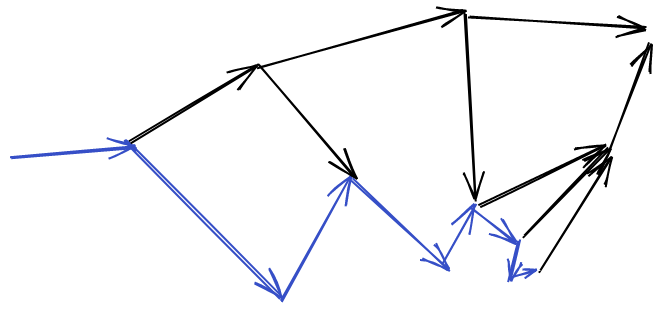

Now, the rough idea we had earlier was to pick a point in the intersection of each projection, and then use that. Let’s say we pick $\frac{1}{3}$ and $\frac{2}{3}$. The problem is that $(\frac{1}{3}, \frac{2}{3})$ is not in the intersection $\bigcap \mathcal{A}$, in the product $[0, 1] \times [0, 1]$:

It’s possible to make the “wrong” choice when considering each component in isolation. We need to use the way that our collection $\mathcal{A}$ puts constraints on each component at the same time, when finding our point. We’ve gotten rid of this global information by limiting ourselves to considering just the component collections $\pi_X(\mathcal{A})$, and $\pi_Y(\mathcal{A})$.

We can amend this by choosing a larger collection of sets that contains $\mathcal{A}$. Let’s now add in all the rectangles centered on the same segment $ab$, but where the “top” can vary as well:

Now this collection “hones in” precisely on the point $(\frac{1}{3}, \frac{1}{3})$, and our method of construction works, since the projections of this set have to end up at $\frac{1}{3}$ as well.

The reason our original collection didn’t work is because $\pi_1(C) \times \pi_2(C) \neq C$ in general, and especially not in this case. When we project down the line segment, and then glue each projection back up, we end up with something way too big:

On the other hand, when we have a single point, things work out just fine:

Lessons Learned

In a sense, the collection $\mathcal{A}$ was not strict enough to force each component to be coherent, and so it was possible to make the “wrong” choice. We have too much freedom in our choice for each component, so it’s possible to not respect the conditions that $\mathcal{A}$ imposes between the different components.

Now, in this specific case, it’s easy to find a collection $\mathcal{B} \supseteq \mathcal{A}$ that that’s strong enough to force our components to be coherent. But in general, we can’t leave this up to chance or observation, we need a fool-proof method to make this work.

What we’re going to do is simply consider all such collections. If we consider the biggest set with the finite intersection property that contains $\mathcal{A}$, we’ll be able to use all of the insight we could ever gleam from picking a collection by hand.

Another way to think about this is that for any collection $\mathcal{C}$, we can find an intersection of $\overline{\pi_\alpha(\mathcal{C})}$ by compactness. If we restrict ourselves to just doing this for the one collection we’ve been given, we’re not exercising the full power of compactness. The more sets are in a collection the more “difficult” it is to find a point in the intersection of these sets. By using the biggest possible collection containing $\mathcal{A}$, we exercise the full power of our assumption that $X_\alpha$ is compact.

A general lesson about proving theorems is that you should try and use exactly the power you’ve assumed. If you can prove something without one of your assumptions, you should remove the assumption, and obtain a more general theorem. If you don’t exercise the full power you’ve acquired, you’re making the proof harder to obtain.

Zorn’s Lemma

Given some collection $\mathcal{A}$, with the finite intersection property, we’d like to show that there’s a “biggest” collection $\mathcal{D}$ containing $\mathcal{A}$, and satisfying the finite intersection property.

The problem with trying to construct this object is that the “super-collection”: $$ \{\mathcal{D} \ |\ \mathcal{D} \supseteq \mathcal{A},\ \mathcal{D} \text{ FIP} \} $$ is pretty unwieldy. In fact, it’s very uncountable. Super uncountable, if you will. Trying to build it directly, or using induction, is going to fail immediately.

On the other hand, there’s never any obstacle stopping us from buildind this mega-set. If at some point we’re working on our collection $\mathcal{D}$, and we’ve realized that there’s an even bigger $\mathcal{D'}$ that works, then we can just use that instead, and keep chugging on.

If we ever encounter some kind of obstacle, we can swiftly adjust our course around it, or incorporate whatever information it’s signalling to us.

This is the kind of situation in which Zorn’s lemma applies. We’re trying to build a big object, that requires considering an infinite number of steps, but where no obstacle to our construction ever pops up.

Theorem: (Zorn’s Lemma) Given a partially ordered set $(X, \leq)$, if every chain (totally ordered subset) $C \subseteq X$ has an upper bound in $X$, then $X$ has a maximal element.

Proving this is far beyond the scope of this post. Essentially, this theorem is taken as an axiom. At least, that’s how I think of it. Using set theory, and assuming the axiom of choice, you can prove this lemma. In fact, this lemma is equivalent to the axiom of choice. Morally speaking, the axiom of choice is inoffensive, and used constantly throughout Topology, but Zorn’s lemma seems much more powerful, and used, just not constantly.

But, this feeling is just an illusion, because once you’ve assumed the axiom of choice, you have no choice but to accept Zorn’s lemma as well.

Thankfully, I have no moral qualms about using Zorn’s lemma, and I actually find it kind of cool when I do get to use it, so let me show you how to apply it in our case.

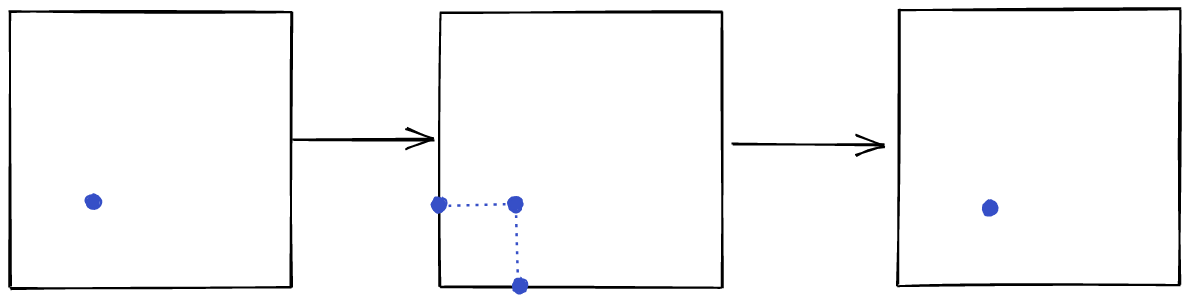

Another way of thinking about this is that if you want to show me that there’s always a bigger object that exists, you’d need to come up with some kind of chain in this order that goes on forever:

The thing is, if I can show that any chain, by virtue of being a chain, without any assumption of finiteness, or any other condition on its size, is bounded, then I can prevent you from ever finding a witness to the non-existence of my mega-object.

This is chiefly non-constructive, since we’re saying that an object exists by virtue of our inability to disprove its existence, but I digress.

The biggest FIP

Concretely, we’ll be proving the following theorem:

Theorem: Given a set $X$, and a collection of subsets $\mathcal{A}$ of $X$, with the FIP property, there exists a collection $\mathcal{D}$ containing $\mathcal{A}$ and with the FIP property, that is not strictly contained in any other such collection.

Proof:

As hinted at, we’ll be using Zorn’s lemma. The first step in applying it is to find a partially ordered set. Consider:

$$ \mathcal{A}_\subseteq := \{\mathcal{B} \ |\ \mathcal{A} \subseteq \mathcal{B},\ \mathcal{B} \text{ FIP}\} $$

For the partial order $\leq$, we’ll be using $\subseteq$.

A maximal element $\mathcal{D}$ of this set would be a collection satisfying all the properties we want. We can use Zorn’s lemma to find this collection, provided that every chain has an upper bound.

Let’s say we have a chain $\frak{B}$. This means that for any $\mathcal{B}, \mathcal{C} \in \frak{B}$ either $\mathcal{B} \subseteq \mathcal{C}$ or $\mathcal{C} \subseteq \mathcal{B}$. We need to show that this super-collection has an upper bound in $\mathcal{A}_\subseteq$.

If this chain is empty, simply take $\mathcal{A}$ as an upper bound.

If it is not empty, let’s just take the union of all of the collections:

$$ \mathcal{U} := \bigcup_{\mathcal{B} \in \frak{B}} \mathcal{B} $$

Certainly, this is an upper bound, so we just need to check that it is contained in $\mathcal{A}_\subseteq$.

First, it obviously contains $\mathcal{A}$. Because the chain is non-empty, we have some $\mathcal{B} \subseteq \mathcal{U}$. By assumption $\mathcal{A} \subseteq \mathcal{B}$, since we’ve taken a chain in $\mathcal{A}_\subseteq$.

Secondly, it satisfies the FIP property. Given sets $C_1, \ldots, C_n \in \mathcal{U}$, there exists, by definition, collections $\mathcal{B}_1, \ldots, \mathcal{B}_n$, with $C_i \in \mathcal{B}_i$. Since the indices are arbitrary, assume $\mathcal{B}_i \subseteq \mathcal{B}_n$. Then, $C_i \in \mathcal{B}_n$ as well, alongside all of the others. Their intersection, $C_1 \cap \cdots \cap C_n$ is non-empty, since $\mathcal{B}_n$ has the FIP.

Having shown that every chain in $\mathcal{A}_\subseteq$ has an upper bound, we can now apply Zorn’s lemma, and obtain a maximal collection $\mathcal{D}$.

$\square$

This collection is closed under finite intersection:

Lemma: Given $D_1, \ldots, D_n \in \mathcal{D}$, the intersection $D_1 \cap \cdots \cap D_n$ is also in $\mathcal{D}$.

Proof:

Given $D_1, \ldots, D_n \in \mathcal{D}$, define: $$ \begin{aligned} E &:= \bigcap_{i = 1}^n D_i \cr \mathcal{E} &:= \mathcal{D} \cup \{E\} \end{aligned} $$ We now show that $\mathcal{E}$ has the FIP, which implies $\mathcal{E} = \mathcal{D}$, and thus $E \in \mathcal{D}$, by maximality.

Let’s say we have $E_1, \ldots, E_m \in \mathcal{E}$. If these consist entirely of elements of $\mathcal{D}$, then we have no work to do, since their intersection is non-empty, by assumption.

So, we only need to consider the case where we have: $E, E_1, \ldots, E_m \in \mathcal{E}$.

We have:

$$ \begin{aligned} E \cap E_1 \cap \cdots \cap E_m \cr D_1 \cap \cdots \cap D_n \cap E_1 \cap \cdots \cap D_m \end{aligned} $$

This is a finite intersection of elements of $\mathcal{D}$, so non-empty.

We now conclude that $D_1 \cap \cdots \cap D_n \in \mathcal{D}$.

$\square$

This collection is so all-encompassing, that if a set touches every set in the collection, it must itself be in the collection.

Lemma: If $B$ is a subset of $X$, intersecting every element of $\mathcal{D}$, then $B \in \mathcal{D}$

Proof:

We show that $\mathcal{D} \cup \{B\}$ has the FIP, which makes it equal to $\mathcal{D}$, meaning $B \in \mathcal{D}$ in the first place.

We use a similar strategy as before.

Given $D_1, \ldots, D_n \in \mathcal{D} \cup \{B\}$, we need to show that their intersection is non-empty.

If each $D_i$ is in $\mathcal{D}$, then this is true by assumption.

Therefore, assume we’re in the situation with $B, D_1, \ldots, D_n$. By the previous lemma the intersection: $$ D := D_1 \cap \cdots \cap D_n $$ is in $\mathcal{D}$. Then we have that $B \cap D$ is non-empty by assumption, since $B$ intersects every $D \in \mathcal{D}$.

$\square$

Proving our Theorem

We can now use this strategy to prove our theorem:

Tychnoff’s Theorem: Given a collection $\{X_\alpha\}$ of Compact spaces, the product $\prod_\alpha X_\alpha$ is also a Compact space.

Proof: Let $\mathcal{A}$ be a collection of closed sets with the FIP. We show that the intersection:

$$ \bigcap_{A \in \mathcal{A}} \overline{A} $$

is non-empty. If this were a collection of closed sets, this would be the intersection $\bigcap \mathcal{A}$. Compactness thus follows from showing this.

Now, we can find a maximal collection $\mathcal{D}$ containing $\mathcal{A}$, and satisfying the FIP, as we’ve developed earlier.

If $\bigcap_{D \in \mathcal{D}} \overline{D}$ is non-empty, then certainly $\bigcap_{A \in \mathcal{A}} \overline{A}$ would also be non-empty.

Consider the collection:

$$ \{\pi_\alpha(D) \ |\ D \in \mathcal{D}\} $$

This set satisfies the FIP, because:

$$ \pi_\alpha(D_1 \cap D_2) \subseteq \pi_\alpha(D_1) \cap \pi_\alpha(D_2) $$

(this observation holds for any function $f$)

By compactness of each $X_\alpha$, we can then choose a point $x_\alpha$ such that:

$$ x_\alpha \in \bigcap_{D \in \mathcal{D}} \overline{\pi_\alpha(D)} $$

Let $\bold{x} = (x_\alpha)$ by the product of these components. We need to show that $\bold{x} \in \bigcap_{D \in \mathcal{D}} \overline{D}$.

If we have a sub-basis element $\pi_\alpha^{-1}(U_\alpha)$, then we can show that it intersects every $D \in \mathcal{D}$.

Since $x_\alpha \in \overline{\pi_\alpha(D)}$ by definition, so we have $U_\alpha$ intersecting $\pi_\alpha(D)$ in some point $\pi_\alpha(\bold{y})$, with $\bold{y} \in D$. It’s clear that $\bold{y} \in \pi_\alpha^{-1}(U_\alpha) \cap D$.

Since $\pi_\alpha^{-1}(U_\alpha)$ intersects every $D \in \mathcal{D}$, it belongs to $\mathcal{D}$, because of $\mathcal{D}$ being maximal, as we proved earlier.

Since basis elements in the Product Topology consist of finite intersections of these subsets, basis elements containing $\bold{x}$ are also in $\mathcal{D}$, since $\mathcal{D}$ is closed under finite intersection, as we showed earlier.

Since $\mathcal{D}$ has the FIP, any element in $\mathcal{D}$ intersects every other element. Thus, any basis element containing $\bold{x}$ intersects every $D \in \mathcal{D}$. This means that any neighborhood of $\bold{x}$ intersects every $D \in \mathcal{D}$, that is to say:

$$ \bold{x} \in \bigcap_{D \in \mathcal{D}} \overline{D} $$

This means that $$ \bigcap_{A \in \mathcal{A}} \overline{A} \neq \emptyset $$ which implies that $\prod_\alpha X_\alpha$ is compact.

$\square$

Conclusion

This post likely wasn’t all that enlightening unless you were already familiar with products and compactness. If you liked the illustrations nonetheless, and are curious to learn more, I’d recommend reading a bit of Munkres, which is linked in the next section.

References

[1] Munkres, James R. Topology; a First Course. Prentice-Hall, 1974.