Some Thoughts on Numeric Classes

This is just a quick post, crystallizing some of the ideas I’ve had recently about organizing numeric classes in Haskell.

These classes are the usual way of overloading the familiar arithmetic

operators (+, -, * and their buddies) for various types. Personally,

I think that they could benefit from a bit of spring cleaning.

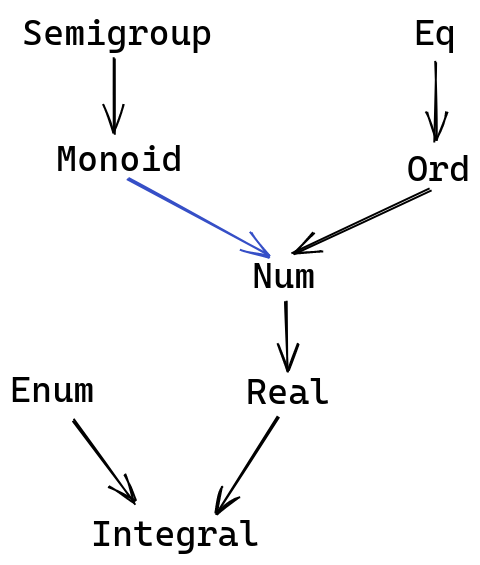

Haskell’s Hierarchy

Here’s an overview of Haskell’s hierarchy of typeclasses:

You can see the different typeclasses involved, and the dependencies linking all of them together.

Eq

The first class is Eq,

giving us decideable equality for a type:

class Eq a where

(==) :: a -> a -> a

Naturally, this defines the == operator we all know and love. This

must be an equivalence relation, satisfying:

x == x

x == y -> y == x

x == y, y = z -> x = z

Ord

Then you have Ord,

which augments Eq with comparisons:

class Eq a => Ord a where

compare :: a -> a -> Ordering

(I’ve simplified things a bit here)

And the Ordering type is a simple enumeration:

data Ordering = LT | EQ | GT

It’s clear that Ord should entail Eq, since we can just check whether

compare returns EQ for equality.

Using compare, the standard comparison operators <, >, <=, >= can all be provided.

While Ord doesn’t specify any laws itself, it’s common to assume that <= is

a partial order, satisfying:

x <= x

x <= y, y <= z -> x <= z

Semigroup

Now we get to the “algebraic” classes.

The first of these is Semigroup:

class Semigroup a where

(<>) :: a -> a -> a

The only thing we assume about this operator is its associtivity:

a <> (b <> c) = (a <> b) <> c

Monoid

Monoid

augments the Semigroup class with an identity element:

class Semigroup a => Monoid a where

mempty :: a

This element satisfies:

x <> mempty = x

mempty <> x = x

Enum

Next, we have the Enum class:

class Enum a where

toEnum :: Int -> a

fromEnum :: a -> Int

The main purpose of this class is to provide semantics for the

[a..b] syntax. Otherwise, this is more of a pragmatic class, instead of

one with some underlying algebraic idea.

Num

And now we have the infamous Num class:

class Num a where

(+) :: a -> a -> a

(*) :: a -> a -> a

negate :: a -> a

abs :: a -> a

signum :: a -> a

fromInteger :: Integer -> a

This is a big amalgamation of everything you’d expect numbers to be, and

then some more. The main purpose of this is to interpret the operators

mentioned here, including - as well, and to interpret numeric literals,

like 3, or 420, using the fromInteger method.

In my opinion, this class is pretty ugly, and perhaps my central motivation in wanting to think about some ways to reform this hierarchy.

Real

Now, you have another ad-hoc class, called Real:

class (Num a, Ord a) => Real a where

toRational :: a -> Rational

I confess that I’ve never used this class all that much. Ostensibly,

its purpose is just to provide a means to convert some type into

rational numbers, which provides a direct means for comparision,

hence the Ord instance.

If we can think of elements of a type as being rational numbers, it’d make

sense to also stipulate that they’re numbers, using the inferred operations.

The Num requirement makes sense, under this interpretation.

Integral

Finally, we have the Integral

class:

class (Real a, Enum a) => Integral a where

quotRem :: a -> a -> (a, a)

toInteger :: a -> Integer

(Simplifying a bit here, but these form a complete definition).

Basically, this is for types that are equivalent to integers, and we have the

corresponding division operations we expect to have for integers:

mod, div et alii.

Interlude: Two Worlds

So far, we’ve seen a basic overview of the numeric hierarchy. For the most part,

it gets the job done. We can calculate useful things, while also being somewhat

generic over the numeric types we use. This allows Haskell to have a principled

approach towards providing standard arithmetic for the various integer types,

like Word, Int, Int64, etc.

That being said, I think there are a few thorns with the organization of these classes. Analyzing the structure of the hierarchy a bit more can help illuminate these issues.

The Mathematical Classes

There are a few classes that are inspired by Math. For example, Semigroup

and Monoid are chiefly mathematical concepts. Formally, a Semigroup is

a set $S$ equipped with an operation $\cdot$, satisfying:

$$ x \cdot (y \cdot z) = (x \cdot y) \cdot z $$

A Monoid is a Semigroup with an element $e$, serving as the identity element:

$$ \begin{aligned} x \cdot e &= x \cr e \cdot x &= x \end{aligned} $$

The Eq class is also inspired by Math. The == operator is modeled

over an Equivalence Relation, which is really just a mathematical definition

of the familiar notion of equality.

While Ord, technically speaking, doesn’t specify any laws, we can model

the Ord typeclass after a Partial Order. This is a set $S$, equipped

with a relation $\leq$, satisfying:

$$ \begin{aligned} &x \leq x \cr &x \leq y, y \leq z \implies x \leq z \end{aligned} $$

The common thread here is that each of these classes correspond to some kind of mathematical object, with corresponding laws.

The Pragmatic Classes

The remaining classes we’ve seen are more loosely defined, and fall

into what I call the “pragmatic classes”. The chief example here is

Num. These classes, as I see them, are about defining useful operations,

caring more about having a vector to provide operators, over

representing some kind of principled abstraction.

Very often, these are conceived of as providing a general class of types

that “behave like” some other concrete type. For example,

Real represents types that are essentially like the Rational type.

The disadvantage in this kind of class is that the operations involved

are often lawless, and sometimes instances have to cheat. Many Num

instances have to bend some of the rules a bit, since not all operations

make sense for that type. This happens because the Num abstraction is

an ad-hoc generalization of the well-known integer type, and not a

more principled collection of operations and laws.

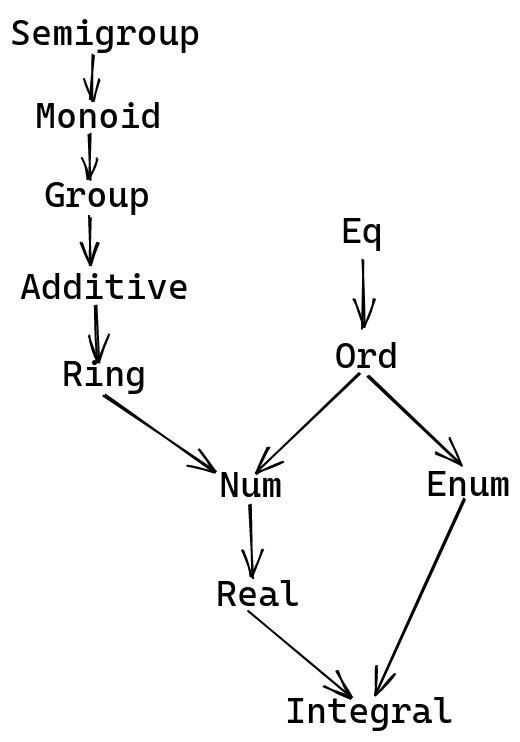

A Proposed Hierarchy

I don’t think I’ve found the perfect solution to making a hierarchy of numerical classes, nor do I think such a solution can be found, but I do have a few ideas on making things a bit better.

Here’s an alternative hierarchy of classes:

Semigroup, Monoid

These are the same classes that we’re used to, inspired by the same mathematical objects:

class Semigroup a where

(<>) :: a -> a -> a

class Semigroup a => Monoid a where

mempty :: a

Group

Mathematically, a Group is a Monoid, where each element $a$ has an inverse $a^{-1}$, satisfying:

$$ a \cdot a^{-1} = e = a^{-1} \cdot a $$

This leads to the following type-class:

class Monoid a => Group a where

negate :: a -> a

Additive

Mathematically, this models an Abelian Group, which is just a group, but where the group operation is commutative, i.e.:

$$ a \cdot b = b \cdot a $$

It’s common to use $+$ for the group operation instead.

This gives us the following typeclass:

class Group a => Additive a where

(+) :: a -> a -> a

This class serves to introduce the + operator, which has to be commutative.

The additional rule is that + and <> have to coincide.

We can also define:

(-) :: Additive a => a -> a -> a

a - b = a + negate b

Ring

Mathematically, a Ring is an Abelian Group, equipped with multiplication as well, satisfying:

$$ a(b + c) = ab + ac (b + c)a = ba + ca 1a = a = a1 $$

This gives us the following typeclass:

class Additive a => Ring a where

(*) :: a -> a -> a

one :: a

satisfying the associated laws.

Choosing Instances

Given some Ring, we have a Monoid instance, matching up with addition +. We might

also want to use multiplication instead, leading us to define the following wrapper:

newtype Multiply m = Multiply m

instance Ring m => Semigroup (Multiply m) where

(<>) = (*)

instance Ring m => Monoid (Multiply m) where

mempty = one

We can use this wrapper to select the right version of Monoid, which is useful.

Num

Now we move on from the nice mathematical classes, to the more pragamatic classes.

First, we have Num. Having already defined many ring operations, we’re left with just:

class Ring a => Num a where

fromInteger :: Integer -> a

Note that we’ve taken the liberty of removing abs and signum, which aren’t particularly

principled to begin with. If these are crucial, I would recommend either sticking them

in the Integral class, or creating an extra class after Num, to contain them.

We use the Num class to interpret numeric literals.

Enum

This remains unchanged, although now we have an Ord requirement.

This makes sense in my view, since you can use the enumeration indices to compare two

elements, and this always makes sense.

Real

For Real, the idea is unchanged. We have a class that represents the ability

to convert to rational numbers.

Integral

This works the same way as it did previously, with conversions back to integers, and the corresponding division operations defined therein.

Roundtripping

Given that Integral implies Num, it might be a good idea to add an additional law,

specifying that the behavior of the newly added division operators can be derived

through first converting to Integer, performing the operation there,

and then converting back to the original type.

Conclusion

I’m not entirely satisfied with the tail end of the hierarchy, and I wonder if a better approach to the so-called “pragmatic classes” might exist.

Another big hole I’ve left is conversions that might possibly fail. For example, converting large integer types into smaller integer types.

That being said, I’m pretty happy with the algebraic side of things, and I really think that the addition of Groups would be quite useful, given how much love Monoids have seen so far.