(Haskell in Haskell) 3. Parsing

This is the third post in the Haskell in Haskell series.

In this post, we’ll go over creating a parser for our subset of Haskell. This stage of the compiler is responsible for taking the tokens that our lexer produced in the previous part.

As usual, both the code for this part, and the entire compiler are available.

Because of all the work we did last time, this part should actually be simpler. We’ve already broken up our source code into bite-size tokens, using whitespace to infer semicolons and braces. Having this clean representation makes our parser’s job much easier.

Parsing in Theory

Before we start coding our parser, let’s try and figure out what a parser is supposed to do, and why we need one anyways.

The goal of parsing is to go from our source code, to a representation that we can actually work with. We want to transform Haskell code like:

foo = 2 + 3 * 4

into some kind of data structure that we can progressively analyze and transform into C code. We’ll need to analyze things like the scoping of names, and the usage of types. We’ll also be gradually transforming and simplifying our representation, with the goal of getting closer and closer to C.

We’ve already written one chunk of this parsing: the lexer. The lexer takes some source code, and groups it up into small tokens. Each token doesn’t make sense as separate chunks. Our parser needs to take these tokens, analyze their structure, and produce a data structure representing the source code.

More than Tokens?

Our lexer already gives us a data structure: a list of tokens. Why not just use this to represent Haskell code?

Unfortunately, this isn’t going to work; the tokens aren’t expressive enough to really reflect the structure of Haskell.

Take this example:

x = 2 + 2

y = 2

After lexing, we get a flat stream of tokens:

{ x = 2 + 2 ; y = 2 }

But this flat representation fails to capture the nested nature of this snippet. A better representation would be something like:

(

(x = (2 + 2))

(y = 2)

)

The expression 2 + 2 “belongs” to the definition of x, and the expression

2 “belongs” to the definition of y. This kind of nested structure

is ubiquitous throughout Haskell. A list of tokens

is simply a bad fit here.

Trees

On the other hand, this kind of nesting is perfect for a tree.

Let’s take our previous example once more:

x = 2 + 2

y = 2

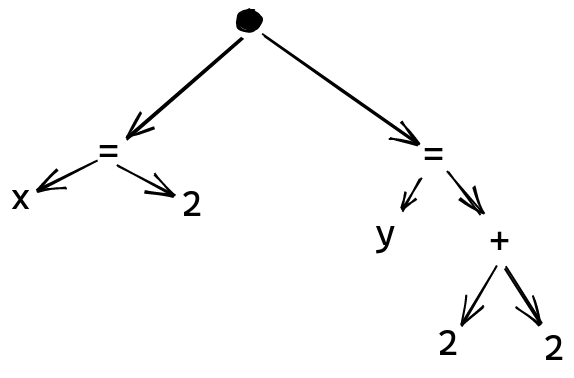

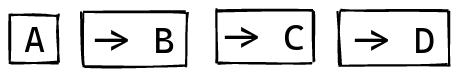

This piece of code can be represented by a tree that looks something like this:

Each node in the tree has some kind of label, and can contain other subtrees as children.

We have a node at the top level, containing all the top level definitions.

Definitions

use an = here, have the name as one child, and the expression as the other.

Addition uses a + node, with its arguments as children.

This approach scales nicely to expressions with even more nesting:

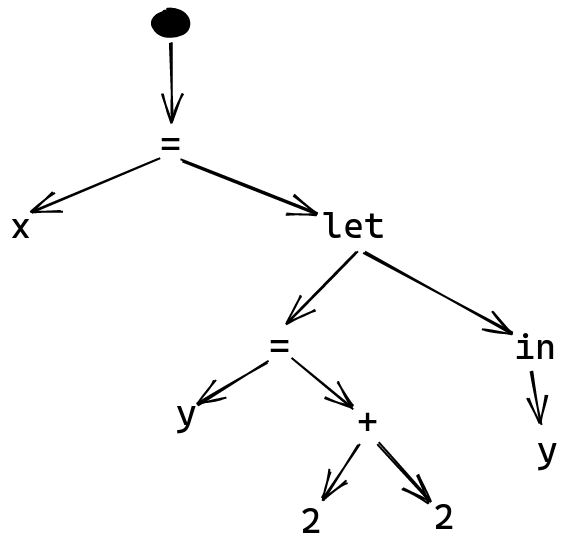

x =

let y = 2 + 2

in y

We now have a two nested expressions for x, giving us a tree that looks like:

We can imagine how this might work for even more complicated expressions, since nodes can contain arbitrary trees as their children.

Valid Syntax vs Valid Semantics

This tree of nodes built up from source code is called an Abstract Syntax Tree, or an AST, for short. It’s a syntax tree, since it represents the structure of our programming language: what syntax is valid or not. I don’t actually know why it’s called an abstract tree, but I like to think that it’s abstract, because it provides a representation of trees that are syntactically valid, but that don’t necessarily make any sense.

For example, take this snippet:

x =

let y = "34" + 3

in "x" foo

This bit of code is syntactically valid, and our parser shouldn’t complain. It still has a few issues though:

- You can’t add strings and numbers

- You can’t use a string like

"x"as a function - The name

foois not defined in this scope

Because of these issues, our program is semantically invalid, even though it manages to parse. The goal of the type checker is to find all of these issues. We’ll get to this soon enough, but not in this part.

It’s not our parser’s job to figure these things out yet. Our parser is just concerned with producing this Abstract Syntax Tree. The parser will be taking the tokens produced by the lexer, and transforming them into this tree.

Grammars

One common tool used to describe these syntax rules is a Context Free Grammar, or just Grammar for short. Grammars allow us to think about the structure of a programming language, at least at the level of syntax.

As a motivating example, let’s take a very simplified subset of Haskell.

Our example language consists of a single expression, which might be one of:

A string literal:

"foo"

An int literal:

345

A variable name:

x3

Or, a let expression, with explicit braces and semicolons:

let {

x = 3;

y = 2;

} in x

A Grammar for this language would like something like this:

<expr> ::= <int> | <string> | <name> | <letexpr>

<letexpr> ::= let { <definitions> } in <expr>

<definitions> ::= <singleDefinition> ; <definitions> | <empty>

<singleDefinition> ::= <name> = <expr>

Each <rule> references some type of syntactic element. For example, <expr>

references

an expression in our little language. After the ::=, we declare each

way we can build up this element. Everything outside of angle brackets

is an actual token we expect to see.

For <expr>, this matches the overview we gave earlier: an expression is either

an integer literal, a string literal, a name, or a let expression.

And then, <letexpr> consists of the token let, followed by some definitions inside

braces, the token in, and an expression.

<definitions> is either empty, or a single definition followed by a ;,

and some more definitions.

Finally, <singleDefinition> represents things like x = 3.

This is just a name, the token =,

and then an expression.

Intuitively, this grammar allows describes the rules that define what structure our toy language has. These kinds of rules should actually be familiar for us, since our lexer used a similar approach.

For example, to define what a token was, we built

up a large lexer from smaller possibilities:

token :: Lexer (Token, String)

token = keyword <|> operator <|> literal <|> name

This matches up naturally with a grammar like:

<token> ::= <keyword> | <operator> | <literal> | <name>

<keyword> ::= let | do | ...

...

The big difference is that our tokens were completely flat. Tokens never contained other tokens. Grammars, on the other hand, allow us to talk about recursive structures as well. Our toy language has a recursive structure: expressions can contain let expressions, which also contain expressions. Because of this, you can nest expressions inside of eachother:

let {

x = 2

} in let {

y = x

} in let {

z = y

} in z

Grammars should also seem eerily familiar to you as Haskeller. In Haskell, we have algebraic data types.

For example, let’s define a type for colors. A color can be either red, blue, green, or an arbitrary hex string like “#ABFE00”.

We could represent this with an ADT, like this:

data Color = Red | Blue | Green | Hex String

But, if you squint a bit, this looks kind of like a grammar:

<color> ::= red | blue | green | # <string>

If we revisit the grammar for our toy language:

<expr> ::= <int> | <string> | <name> | <letexpr>

<letexpr> ::= let { <definitions> } in <expr>

<definitions> ::= <singleDefinition> ; <definitions> | <empty>

<singleDefinition> ::= <name> = <expr>

We can go in the other direction, from grammar to ADT, modelling this structure using Haskell types:

data Expr

= IntExpr Int

| StringExpr String

| NameExpr Name

| LetExpr [Definition] Expr

data Definition = Definition Name Expr

There’s not a one-to-one correspondance here, since the grammar is also concerned with syntactic elements, like semicolons, and braces, and we don’t care about those here. But the rough structure is the same, especially in terms of how the data type references itself recursively.

Because Haskell has these nice recursive ADTs, we can have our syntax tree look very similar to the grammar for our language.

We won’t be using grammars directly, but we’ll be doing awfully similar things. I also think it’s important to touch on the concept of grammars, at least briefly, since most of the other resources you’ll read about parsing will use them heavily.

Parser Combinators

Alright, now it’s time to start writing some code. Before we start defining the structure of our syntax tree, or writing the parser itself, we first need to write our tool of choice for making parsers: the Parser Combinator! This is going to be a suped up version of the Lexer Combinator tool we made last time, extended to handle recursive structures!

Let’s first create a module for our parser in our cabal file:

exposed-modules: Ourlude

, Lexer

, Parser

Now let’s go setup the standard module and imports in src/Parser.hs:

{-# LANGUAGE LambdaCase #-}

module Parser where

import Control.Applicative (Alternative (..), liftA2)

import Data.List (foldl')

import Lexer (Token (..))

import Ourlude

We have LambdaCase as a convenient extension in this module. We also import

Alternative, as well as some other utilities.

From Lexer Combinator to Parser Combinator

With Lexer Combinators, a lexer was essentially just a function:

input -> Maybe (a, input)

We take in some input, and then either fail or succeed, returning a value, and the remaining input. This works well for lexing, since a lexer can only produce one result, and it’s always obvious which of two options we need to choose: just use the longest match rule.

This won’t work for parsing. Our structure is much more complicated, so it’s not always obvious that the longest match rule will be correct. What we do instead is to let ambiguity happen, at least temporarily. Instead of either failing, or returning a single way of consuming the input, we return all possible ways to proceed forward.

We now have:

input -> [(a, input)]

By the time we’ve parsed the entire source code, there should be only a single element

in this list. Otherwise, there are multiple ways of parsing some code. For example,

a parser that doesn’t handle operator precedence might see 2 + 3 * 4 and produce both:

(2 + 3) * 4

2 + (3 * 4)

Of course, the second option is correct, because * has higher precedence than +, as we’ll

see later.

Ambiguity in the parsing process is fine, as long as we resolve it later. We might need more than one token to resolve this ambiguity, which is ok. As a chief example, take where expressions. These are expressions with the definitions coming after the body they’re used in:

x + y

where

x = 2

y = 3

If in our parser for expressions, we have some rule like:

expr = notWhereExpr <|> whereExpr

Then we’ll have some ambiguity here. This is because we can’t tell which of these parsers is correct

until we see the where token. For the first 3 tokens,

we have multiple options floating around.

By the time we finish parsing the file, we shouldn’t have any ambiguity left. If we do, then that means that there are multiple ways of interpreting some code. This is basically never a problem in the code itself, but a problem in the implementation of the language. There are certain languages that are inherently ambiguous, like C++, in which case the parser needs to make an arbitrary choice, but Haskell is not ambiguous. If we fail to parse something because of ambiguity, that’s probably a bug in our parser.

The Concrete Type

With all of this in mind, we can go ahead and define a concrete type for Parser:

newtype Parser a = Parser {runParser :: [Token] -> [(a, [Token])]}

This is very similar to our Lexer type from the last part. Instead of working over String,

we know work over [Token], instead.

We also return multiple possible ways of parsing, as explained earlier.

Example Building Blocks

To learn how this works better, let’s go ahead and make a couple basic helpers.

First, let’s make a little helper that accepts a single token:

satisfies :: (Token -> Bool) -> Parser Token

satisfies p =

Parser <| \case

t : ts | p t -> [(t, ts)]

_ -> []

This is analogous to Lexer.satisfies, which accepted a single character.

Our implementation looks at the remaining list of tokens,

and checks if there is a token matching our predicate

at the front of the list.

If so, we return that token, along with the remaining input. Otherwise

we return an empty list, since there’s no way for this parser to succeed.

An immediate application of this satisfies function is going to be:

token :: Token -> Parser Token

token = (==) >>> satisfies

This just matches against a specific token that we provide.

A similar function to satisfies is going to be pluck:

pluck :: (Token -> Maybe a) -> Parser a

The behavior is going to be the same as satisfies, except now we

can return a value

if the predicate matches. This is useful, because we have a few tokens like

IntLit i and StringLit s which also have an argument. This helper

lets us match against a token like this, extracting the argument. For example, we can do:

pluck <| \case

IntLit i -> Just i

_ -> Nothing

to get a parser that accepts an int literal, but produces an Int.

The implementation of pluck is similar to satisfies:

pluck :: (Token -> Maybe a) -> Parser a

pluck f =

Parser <| \case

t : ts -> case f t of

Just res -> [(res, ts)]

_ -> []

_ -> []

Just replaces the True case we had previously, but also provides

us with the value we want to return.

Functor and Applicative

Like with Lexer, we’ll be providing instances of Functor and Applicative

for Parser.

For Functor, we have:

instance Functor Parser where

fmap f (Parser p) = Parser (p >>> fmap (first f))

This just maps over the results that we’ve produced. In fact,

this definition is exactly the same as for Lexer, since Maybe

and [] are both Functors!

For Applicative, the operations will mean the same thing as

for Lexer. pure :: a -> Parser a will give us a parser that always succeeds,

consuming no input, and (<*>) :: Parser (a -> b) -> Parser a -> Parser b will

give us a parser that runs the first parser, and then runs the second parser.

The return value will be the function

produced by the first with the argument produced by the second.

The difference with Lexer is that now a parser may return multiple results.

We’re going to use all the combinations of first and second results:

instance Applicative Parser where

pure a = Parser (\input -> [(a, input)])

Parser pF <*> Parser pA =

Parser <| \input -> do

(f, rest) <- pF input

(a, s) <- pA rest

return (f a, s)

pure does exactly what we said it does before, so it’s not too surprising.

What’s neat with <*> is that to implement the “combine all possible functions and arguments”

behavior,

we can use the fact that [] implements the Monad class in the same way that Maybe does,

allowing us to use do notation. For [], instead of allowing us to handle failure,

we are now able to handle “non-determinism”. What ends up happening is

that for each possible pair (f, rest) of a function, and remaining input,

we return each possible way of using the second parser on that input, and then

applying the function on the argument produced.

In practice, most of the time there won’t be any ambiguity, so:

parser1 *> parser2

will simply mean “run parser1, and then run parser2”

On the other hand, if we have:

(parser1A <|> parser1B) *> (parser2A <|> parser2B)

then we’ll get 2 * 2 = 4 paths available to us. We can parse 1A and then 2A,

1A and then 2B, etc.

Alternative

As you might expect, we’ll also be implementing Alternative for Parser,

to get that sweet sweet <|> operator, and all the goodies that come along with it!

We also need an empty :: Parser a function, which returns a Parser that always fails.

instance Alternative Parser where

empty = Parser (const [])

Parser pA <|> Parser pB =

Parser <| \input -> pA input ++ pB input

To get a parser that always fails, we return no valid ways to continue parsing.

For <|>, we run both parsers, and then combine both of their results using ++.

Unlike Lexer, we don’t try to resolve any ambiguity if they both succeed.

As explained earlier, we let the ambiguity exist, by returning all possible

ways of parsing. Our final parser should only end up returning one result though,

even if sub-parsers might temporarily have some ambiguity.

Like last time, the Alternative instance gives us plenty of goodies for free.

For example, we now have many :: Parser a -> Parser [a], which allows

to turn a parser for one item, into a parser for many items, placed one after the other.

There’s also some, which does the same thing, but requires at least one

item.

For example, if intParser accepts 3, then some intParser would accept 3 4 5 6, producing

[3, 4, 5, 6] as our output.

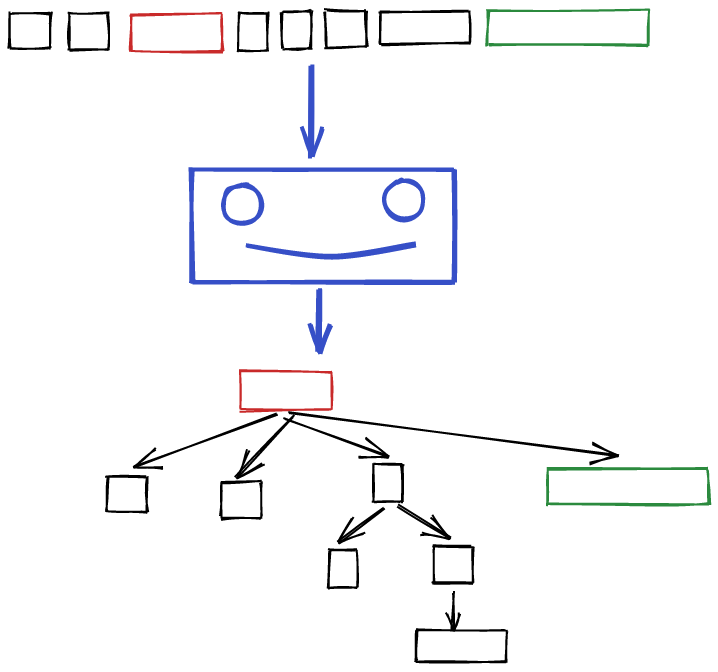

Integrating a Parser

We now have the combinators we need to build our parser. Before we actually start working on parsing our subset of Haskell, let’s go ahead and add a new stage to our compiler. We can get all of this boilerplate out of the way, letting us focus on parsing.

Let’s define a stub type for our syntax tree, and for our errors:

data ParseError = UnimplementedError deriving (Show)

data AST = AST deriving (Show)

Like last time, we just have a single error: the error telling users that our parser is not implemented yet!

Our AST is just a stub data type as well.

We’ll be completing both of these soon enough. For now, we just want to get this stage of the compiler integrated into the command line program.

We also need to write a simple parser function that we can expose

as our implementation of this stage:

parser :: [Token] -> Either ParseError AST

parser _ = Left UnimplementedError

This function will take in the list of tokens produced by the lexer, and return either the parsed syntax tree, or an error, indicating that parsing failed.

Finally, we can add the AST type and the parser function to the the

exports for this module:

module Parser (AST(..), parser)

Adding a new Stage

We now need to go into Main.hs, and add a Stage for the parser. First,

let’s add the Parser module to our list of imports.

-- ...

import qualified Parser

-- ...

Right next to lexerStage, we can go ahead and add a new Stage for our parser:

parserStage :: Stage [Lexer.Token] Parser.AST

parserStage = makeStage "Parser" Parser.parser

The definition of this is essentially the same as we had for lexerStage.

Stages were introduced in great detail

last time,

so feel free to take a quick refresher if you’d like.

We also need to modify our argument parsing to accept “parse” as a stage. This way, users can do:

haskell-in-haskell parse file.hs

in order to print out the AST they get from parsing file.hs.

Of course, they’ll still be able to do:

haskell-in-haskell lex file.hs

to just print out the tokens they get after lexing file.hs.

All we need to do is modify readStage, giving us:

readStage :: String -> Maybe (String -> IO ())

readStage "lex" =

lexerStage |> printStage |> Just

readStage "parse" =

lexerStage >-> parserStage |> printStage |> Just

readStage _ = Nothing

Here we get to use the fancy >-> operator we defined last time, in order

to compose the lexing stage with the parsing stage. This works out nicely,

since the parsing stage consumes the tokens that the lexing stage produced.

We end up with a stage taking in a String for the source code,

and producing the AST that we want to print out.

We can now run all of this, and see something like:

> cabal run haskell-in-haskell -- parse foo.hs

Parser Error:

UnimplementedError

which makes sense, since we haven’t implemented the parser yet. Let’s fix that!

Structure of the AST

Before we can write a parser to convert our tokens into a syntax tree, we need to define the shape of that syntax tree. We’re going to be describing the exact subset of Haskell that we implement, by creating various data types for each construct in the language.

For example, we’re going to have a data type for expressions. One of

the variants will be a binary expression, for things like 1 + 2,

or 4 * 33. Another variant might be function application, for things like

f 1 2 x. etc.

A Rough Idea

Our subset of Haskell is almost cleaved into two distinct parts:

- The part of the language dealing with defining types

- The part of the language dealing with defining values

These 2 parts interact through annotations, which allow us to declare that a given value has a certain type.

For example, if you have:

x :: Int -> Int

x = \x -> x + 1

The Int -> Int is squarely in the domain of types, and we’ll need some data structures

to describe function types like Int -> Int. The lamdba expression \x -> x + 1 is clearly

in the domain of values. And the declaration x :: ... is a point of interaction

between both domains.

Because of this, we can think of our language as being roughly groupable into 3 sections:

- Types: describing them, definining them, creating synonyms

- Expressions

- Definitions: assigning types and expressions to names

There’s a lot of interaction between these categories of course. For example,

let x = 3 in x is an expression that also uses a definition, inside

of the let. With that said, it’s still useful to have a bit of categorization

in our head before we start defining everything we need.

Types

So, the first thing we can do is define how we’ll work with types in this subset

of Haskell. We need ways to refer to certain types, like Int, String.

We also need to be able to use more complicated types,

like (Int -> String) -> String. We’ll

need ways to define new types, either through custom types, like

data Color = Red | Blue | Green, or type synonyms, like type MyInt = Int.

The Fundamental types

Before we get to the definitions of new types, let’s first define our data structures

representing types that exist. For example,

when you have x :: Int -> Int, you need some way of representing the

type that comes after the ::. This is what we’ll be defining now.

Essentially, what we’re doing is defining what a type “is” in our subset of Haskell.

In fact, this definition will be useful beyond just parsing. We can also use

this representation of types in our type checker, for example. Because of this,

we won’t be creating this definition of what at type is in the Parser module,

but instead creating a new module, in src/Types.hs, to hold fundamental data

structures for working with types. We’ll expand on this module in further parts,

as we need to do more things with types.

As usual, let’s edit our .cabal file to add the Types module:

exposed-modules: Ourlude

, ...

, Types

Now, we can go ahead and define this module in src/Types.hs:

module Types where

import Ourlude

For now, we just export everything in the module, but we’ll come back and make the imports explicit once we’ve defined our representation of types.

First, let’s think about what kind of types you should be able to work with in

our subset of Haskell. As mentioned already, we’re going to have a primitive

Int type, the standard integer type we’re used to.

Integer literals will have that type, so 3 :: Int, for example. We’ve already

lost the element of surprise by defining boolean and string literals in the lexer,

so we’re going to also have primitive boolean and string types in

our language, departing from Haskell slightly.

So we have String and Bool as builtin types as well.

In addition to builtin types, we need a way for users to define new types,

and then reference those types. If a user has type X = Int, then

they should be able to say:

y :: X

y = 3

So we need to reference custom types by name, as well.

Our subset will also have support for polymorphism. You can define functions like:

id x = x

The type of this function is polymorphic:

id :: a -> a

Here, a is not a type per se, but rather a type variable. We need a way

to reference type variables by name as well.

This also means that custom data types can be polymorphic, and have variables of their own. For example, you might define a list data type as:

data List a = Cons a (List a) | Nil

This will be valid in our language, and introduces the type List _, where the underscore

needs to be filled in. So you might have List Int as one type,

List String as another, and List a, if a happens to be a type variable in scope.

In brief, custom types are referenced by name, and also have multiple type variables

as arguments.

Finally, we need a way to talk about the function type A -> B, which is also

built into the language.

With all of this in mind, let’s just define our representation of types:

type TypeVar = String

type TypeName = String

infixr 2 :->

data Type

= StringT

| IntT

| BoolT

| CustomType TypeName [Type]

| TVar TypeVar

| Type :-> Type

deriving (Eq, Show)

So, we have the basic primitive types as hardcoded options:

Intcorresponds toIntTin this representationStringcorresponds toStringTBoolcorresponds toBoolT

We have 2 type synonyms, to clarify the difference between TypeVar, which is a lower

case name, like a, used for the name of a type variable, and TypeName, which

is an upper case name, like List or Foo, used to reference the name

of a newly defined type.

Type variables have the variant TVar and take a name as argument. So a in Haskell

would be TVar "a" in our representation.

For newly defined types, we have the name of that type, as well as a list of arguments,

which are also types. List Int would be CustomType "List" [IntT] in this representation.

You can also nest things, so List (List Int) would become

CustomType "List" [CustomType "List" [IntT]]

Note that type synonyms are also under this category. If you have type X = Int,

then you’d use CustomType "X" [] to refer to this type synonym.

Finally, we need a way to represent function types. We create a new operator

:-> for this. (We need the : so that it can be used in types). With this in place

Int -> Int becomes IntT :-> IntT, as expected. Note that we declare

this operator infixr, which means it’s right associative, like -> is in Haskell.

This means that:

Int :-> StringT :-> BoolT

is parsed by GHC as:

Int :-> (StringT :-> BoolT)

which is exactly the behavior that we want.

We’ll be using this representation of types throughout the compiler. Let’s go ahead and explicitly export it as well:

module Types

( Type (..),

TypeVar,

TypeName

)

where

Now, let’s use these types to start working on our syntax tree, back in src/Parser.hs.

Defining new types

The next thing we need to do is add the data structures representing the definitions of new types in our language. There are going to be two ways to define new types:

- Type Synonyms, things like

type X = Int - Data Definitions, things like

data Animal = Cat | Dog

In our language, these are both considered as a kind of definitions

that can appear at the top level. They’ll both be variants of a common

Definition type.

We’ll be needing the items we just defined in the Types module inside of the parser,

so let’s add an import in src/Parser.hs:

...

import Ourlude

import Types (Type (..), TypeName, TypeVar)

First, let’s define type synonyms.

Note that we don’t allow polymorphic things like type List2 a = List a,

only type ListInt = List Int. Because of this, we can define type synonyms

as a simple variant of Definition:

data Definition

= TypeSynonym TypeName Type

A type synonym has a name, which is an upper case name like X, and a type that

it’s equal to.

And then, we need to define the structure of data definitions. The basic idea is that we have a name and some list of constructors:

data MyType = VariantA | VariantB | VariantC

We also need the ability to have arguments in each of the constructors:

data MyType = VariantA String | VariantB Int Int | VariantC

We can also make the data type polymorphic, by specifying some type variables next to the name:

data MyType a b = VariantA String | VariantB Int Int | VariantC

Of course, we can use these type variables inside of the variants:

data MyType a b = VariantA String | VariantB Int Int | VariantC a b

And that’s about it for new data types.

Let’s first define a structure for each of the constructors / variants:

type ConstructorName = String

data ConstructorDefinition

= ConstructorDefinition ConstructorName [Type]

deriving (Eq, Show)

A constructor has a given name, like VariantA, or Cons, as well as a list

of types, which are the arguments for the constructor. For clarity,

we’ve created a separate synonym, ConstructorName, for this kind of name. For example,

the VariantB constructor in our MyType example would be represented as:

ConstructorDefinition "VariantB" [IntT, IntT]

Now, we can add an extra variant in Definition for data definitions:

data Definition

= DataDefinition TypeName [TypeVar] [ConstructorDefinition]

| TypeSynonym TypeName Type

deriving (Eq, Show)

A data definition has a name, a list of type variables, and then a list of constructors.

Our MyType example becomes:

DataDefinition "MyType" ["a", "b"]

[ ConstructorDefinition "VariantA" [StringT],

ConstructorDefinition "VariantB" [IntT, IntT],

ConstructorDefinition "VariantC" [TVar "a", TVar "b"]

]

in this representation.

And now we have a complete way of representing the syntax for defining new types! We’ve already started getting a feel for the tree like structure we’re using to represent our language, and we’re just getting started!

Expressions

In this section, we’ll be defining most of the different kinds of expressions in our language,

except for let and where expressions. These will use definitions, which we’ll define

a bit later.

Literals

This first expressions we have are literals. We have int literals,

like 2 and 245, string literals, like "foo" and "bar", and finally,

boolean literals, namely, True and False. We can define a type Literal

representing these:

data Literal

= IntLiteral Int

| StringLiteral String

| BoolLiteral Bool

deriving (Eq, Ord, Show)

We have one type of literal for each of the primitive types in our language.

Let’s also add a type of expression for literals:

data Expr

= LitExpr Literal

deriving (Eq, Show)

As an example, the literal 3 becomes the much more verbose:

LitExpr (IntLiteral 3)

Names

We can also reference names inside of expressions. For example, if

we have some value x :: Int, we have x + x as an expression. We can also reference

the constructors for different data types, like Nil, Red, etc.

We’ll be representing these names with strings, but for clarity, let’s create a type synonym:

type Name = String

We can then use it to define a kind of expression that just use a name:

data Expr

...

| NameExpr Name

Semantically, the meaning of NameExpr "foo" is whatever expression

"foo" is bound to in a given scope. So if we have foo = 3, then

NameExpr "foo" should evaluate to IntLiteral 3, using our expression syntax.

If Expressions

Next we have if expressions, things like:

if y then 3 else 4

if 2 + 3 > 4 then 4 else x + x

These are straightforwardly defined as:

data Expr

...

| IfExpr Expr Expr Expr

We can have arbitrary expressions inside of the condition, if-branch, and else-branch.

So, if y then 3 else 4 becomes:

IfExpr

(NameExpr "y")

(LitExpr (IntLiteral 3))

(LitExpr (IntLiteral 4))

Lambda Expressions

The next kind of expression are lambda expressions, allowing us to define anonymous functions. These look like:

\x -> x + 1

\x -> \y -> x + y

Note that in Haskell, you can define multiple names at once in a lambda. For example:

\x y -> x + y

is valid, and syntax sugar for:

\x -> y -> x + y

The simplifier will deal with this syntax sugar; our parser will accept this verbatim:

data Expr

...

| LambdaExpr [ValName] Expr

We have a list of named parameters, and then an arbitrary expression using them.

So \x y -> x becomes:

LambdaExpr ["x", "y"] (NameExpr "x")

This is the first time we use the ValName synonym, which is defined as:

type ValName = String

This will be used in many places for names that exclusively refer to values.

So x is a ValName, but something like Nil would rather be typed

as ConstructorName.

Function Application

What would our functional language be without function application? In Haskell, function application just takes arguments separated by whitespace:

f 1 2 3

We can also have some arbitrary expression as the function as well:

(f . g) 1 2

This gives us:

data Expr

...

| ApplyExpr Expr [Expr]

Because of currying, f 1 2 is really sugar for (f 1) 2. But, once

again, we’ll be removing syntax sugar in the simplifier; the parser

needs to accept all of this. So, for now, f 1 2 would be represented as:

ApplyExpr

(NameExpr "f")

[LitExpr (IntLiteral 1), LitExpr (IntLiteral 2)]

Negation

We have a single unary operator in our language: negation. Instead of

having negative numbers, like -3, this is instead the negation operator

- applied to the expression 3. We can also do more complicated things like:

-((\x -> x + 1) 3)

So, we add negation expressions:

data Expr

...

| NegateExpr Expr

This makes the simple -3 into the much more verbose:

NegateExpr (LitExpr (IntLiteral 3))

Binary Operators

With the only unary operator in the language out of the way, let’s add the

many binary operators we need. This will cover arithmetic like a + b + c,

to function composition f . g . h, to comparisons with x > y, etc.

We have:

data Expr

...

| BinExpr BinOp Expr Expr

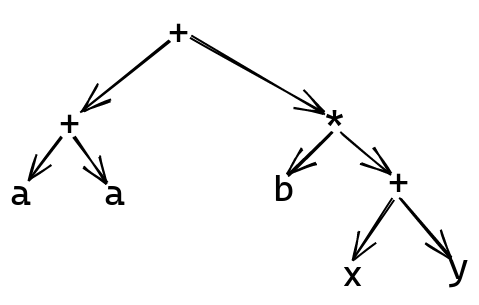

If we have some complex arithmetic expression, like a + a + b * (x + y), this can

still be written as a tree, with each node only having two children:

Or, using the structure we’ve just defined, as:

BinExpr

Add

(BinExpr

Add

(NameExpr "a")

(NameExpr "a")

)

(BinExpr

Mul

(NameExpr "b")

(BinExpr

Add

(NameExpr "x")

(NameExpr "y")

)

)

Of course, we haven’t defined Add or Mul, or any of the other members

of BinOp yet. Let’s briefly go over all of the operators:

data BinOp

= ...

deriving (Eq, Show)

The + operator is used to add two numbers:

= Add

The - operator subtracts the right number from the left number:

| Sub

The * operator is for multiplication:

| Mul

The / operator is for division:

| Div

We have ++ for string concatenation

| Concat

We have the comparision operators <, <=, >, >=, which become:

| Less

| LessEqual

| Greater

| GreaterEqual

And the comparison operators == and /= become:

| EqualTo

| NotEqualTo

We also have the two boolean operators ||, and &&, which are:

| Or

| And

Finally, we have the function “operators”. Namely, $ and .. These are defined

as standard functions in normal Haskell, but since we don’t have custom operators,

these are done here as well:

| Cash

| Compose

Pattern Matching

The next kind of expression we’re going to deal with are case expressions, things

like:

case x of

2 -> x + 2

3 -> x + 3

y -> x + y

or

case x of

Nil -> 0

Cons A (Cons B Nil) -> 1

Cons B Nil -> 2

Cons y Nil -> y

We have some kind of expression that we’re scrutinizing, followed by a series of branches. Each branch has some kind of pattern that we’re matching against, followed by an expression. The value of the case expression is the value of whatever branch happens to match.

So, let’s first define what kind of patterns we have in our language:

data Pattern

= ...

deriving (Eq, Show)

The first kind of pattern is the wildcard: _. This pattern matches against everything,

but creates no new name:

data Pattern

= WildcardPattern

The next kind of pattern is similar. We can also have a name as a pattern, like:

case 3 of

x -> x

This is like the wildcard, but also assigns the value of whatever it managed to

match to the given name. Here, x would have the value 3 inside of the branch.

We have:

data Pattern

...

| NamePattern ValName

We use ValName, since only lower case names like x are valid here.

Another kind of pattern is for literals. We can match against literal ints, like

3, literal strings, like "foo", or literal bools, like True, or False:

data Pattern

...

| LiteralPattern Literal

We also want to be able to match against custom types. If we define a custom

type like data Color = Red | Blue | Green, we need to be able to do things like:

case color of

Red -> ...

Blue -> ...

Green -> ...

If our data type has constructors, like data Pair = Pair Int String,

we want to be able to match against the arguments as well, giving us constructions like:

case pair of

Pair 3 "foo" -> ...

Pair x "bar" -> ...

Pair _ _ -> ...

With this in mind, we need to add a variant for these constructor patterns:

data Pattern

...

| ConstructorPattern ConstructorName [Pattern]

We have the name of the constructor, followed by a sequence of arbitrarily complex

patterns. So, given a data type like data List a = Cons a (List a) | Nil,

and a pattern like:

Cons _ (Cons _ (Cons _ Nil)

we would represent this as:

ConstructorPattern

"Cons"

[ WildcardPattern,

ConstructorPattern "Cons"

[ WildcardPattern,

ConstructorPattern "Cons"

[ WildcardPattern,

ConstructorPattern "Nil" []

]

]

]

And now that we’ve defined patterns, we can immediately define case expressions!

data Expr

...

| CaseExpr Expr [(Pattern, Expr)]

We first have the expression we’re scrutinizing, followed by a list of branches. Each branch contains a pattern, and the expression to use when that pattern matches.

Given an expression like:

case scrut of

0 -> 0

1 -> 1

_ -> 2

we would represent this as:

CaseExpr (NameExpr "scrut")

[ (LiteralPattern (IntLiteral 0), LitExpr (IntLiteral 0)),

(LiteralPattern (IntLiteral 1), LitExpr (IntLiteral 1)),

(WildcardPattern, LitExpr (IntLiteral 2))

]

Definitions

Now that we’ve defined expressions as well as the structure of types, we can combine the two, in order to define the structure of value definitions. This is about the structure of defining new values. In Haskell, there are two parts to a value definition:

- The type annotation, like

x :: Int - The name definition itself, like

x = 3

The type annotation and name definition don’t have to appear together, and the type annotation isn’t necessary at all. Regardless, our parser will need to represent both.

So, let’s create a structure for both of these:

data Definition

= ValueDefinition ValueDefinition

| DataDefinition TypeName [TypeVar] [ConstructorDefinition]

| TypeSynonym TypeName Type

deriving (Eq, Show)

data ValueDefinition

= ...

deriving (Eq, Show)

We’ve just introduced the notion of a ValueDefinition, which will contain both

the type annotations, and the name definitions we’ve just touched upon. We’ve also

added this to our concept of Definition. A definition now includes the two

constructs related to types, namely, data definitions, and type synoyms,

as well as the definitions for values.

For type annotations, the definition is pretty simple:

data ValueDefinition

= TypeAnnotation ValName Type

A type annotation like x :: Int is represented as the name of the value being annotated,

and the type we’re providing after the ::.

For name definitions, our first try might be something like:

NameDefinition ValName Expr

The idea is that something like x = 3 would become:

NameDefinition "x" (LitExpr (IntLiteral 3))

This would work for a large class of Haskell definitions, but Haskell has some more syntax sugar around definitions. The first piece of sugar is that instead of having to write:

id = \x -> x

You can instead move the parameter x to the left side of the =:

id x = x

Of course, you can have multiple parameters as well:

f a b = a + b

So, our structure for name definitions will need to accomodate these named parameters.

Another bit of sugar is that you can pattern match inside of these definitions:

f 0 1 = 1

f 0 _ = 2

f a b = a + b

A function can be defined with multiple “heads”, each of which has patterns for its arguments. Because of this, our full structure for name definitions becomes:

data ValueDefinition

...

| NameDefinition ValName [Pattern] Expr

We have the name used for this value, a list of patterns for each of the arguments, and an expression for the body of this definition.

As an example, this function:

f :: Int -> Int

f 0 = 0

f a = a

Would become 3 separate definitions:

TypeAnnotation "f" (IntT :-> IntT :-> IntT)

NameDefinition "f" [LiteralPattern (IntLiteral 0)]

(LiteralPattern (IntLiteral 0))

NameDefinition "f" [NamePattern "a"] (NameExpr "a")

We have one definition for the type annotation, and 2 more for each of the 2 heads of the function.

Now that we have a structure for definitions, we can add the two missing

types of expressions: let and where expressions. These are

really two ways to express

the same thing: local definitions inside an expression. So:

let x :: Int

x = 2

in x

and

x

where

x :: Int

x = 2

Have exactly the same meaning. For clarity, we’ll just create two different types of expression for each of these:

data Expr

...

| LetExpr [ValueDefinition] Expr

| WhereExpr Expr [ValueDefinition]

The structure is slightly different, to reflect the different order of the two

variants. let has the definitions before the expression, and where has

the definitions after the expression.

Finally, now that we have definitions finished, we can actually define our real syntax tree:

newtype AST = AST [Definition] deriving (Eq, Show)

This just says that a Haskell program consists of a sequence of top level definitions. So, something like:

data Color = Red | Blue | Green

type C = Color

x :: C

x = Red

would be a series of 4 definitions, represented as:

AST

[ DataDefinition "Color"

[ ConstructorDefinition "Red" [],

ConstructorDefinition "Blue" [],

ConstructorDefinition "Green" []

],

TypeSynonym "C" (CustomType "Color" []),

ValueDefinition (TypeAnnotation (CustomType "C" [])),

ValueDefinition (NameDefinition "x" [] (NameExpr "Color"))

]

Whew! We now have a complete AST representing our subset of Haskell! Let’s go ahead and add the necessary data types that our parser needs to export:

module Parser

( AST (..),

ValName,

ConstructorName,

Name,

Definition (..),

ConstructorDefinition (..),

ValueDefinition (..),

Expr (..),

Literal (..),

BinOp (..),

Pattern (..),

parser,

)

where

The next step in this post is to write a parser for our AST, using the little combinator framework we created earlier.

Parsing in Practice

So, now it’s time to use all of the little tools we’ve made in order to build up a parser for our AST. We’re going to be building up a parser in a bottom up fashion, starting with simple parsers for simple parts of the language, and combining them piece by piece to make up a parser for the whole language.

Names and Literals

We’re going to be starting with the simplest form of expression: names,

and literals. There were two types of names in the lexer: LowerName,

for names starting with a lower case letter, and UpperName for names

starting with an upper case letter. We can make a parser for LowerName

pretty easily:

lowerName :: Parser ValName

lowerName =

pluck <| \case

LowerName n -> Just n

_ -> Nothing

Here we use the pluck :: (Token -> Maybe a) -> Parser a function we defined previously.

pluck lets us match against a certain type of token, and also extract some information

about that token. This is useful here, since we want to extract

the string contained in a LowerName token.

We can use the same trick for UpperName:

upperName :: Parser TypeName

upperName =

pluck <| \case

UpperName n -> Just n

_ -> Nothing

The only difference here is that we’re extracting from UpperName instead

of LowerName.

We’ve created a few different synonyms for String, to clarify the different

kinds of names we use throughout our AST: things like

TypeVar, TypeName, ValName, etc. We can immediately put the two parsers

we’ve just defined to use, by creating a parser for each of these syntactic

classes:

typeVar :: Parser TypeVar

typeVar = lowerName

typeName :: Parser TypeName

typeName = upperName

valName :: Parser ValName

valName = lowerName

constructorName :: Parser ConstructorName

constructorName = upperName

Each of these kinds of name is either a lower case name, or an upper case name. In some contexts,

for example, function application, we might need to accept both,

which is why we created the Name synonym. We can add a parser for that as well:

name :: Parser Name

name = valName <|> constructorName

Here we use the <|> for the first time, to indicate that name

is either a valName, or a constructorName, i.e. that we should accept either

the LowerName token, or the UpperName token here.

The next thing we can add in this section is literals. We want to be able to parse ints, strings and bools, which make up the built-in values in our subset of Haskell:

literal :: Parser Literal

literal = intLit <|> stringLit <|> boolLit

where

Once again, we use the handy <|> operator, to say that a literal is either

an integer literal, a string literal, or a bool literal. The lexer has already

done the job of creating a token for each of these, which

makes defining these alternatives very easy:

where

intLit =

pluck <| \case

IntLit i -> Just (IntLiteral i)

_ -> Nothing

stringLit =

pluck <| \case

StringLit s -> Just (StringLiteral s)

_ -> Nothing

boolLit =

pluck <| \case

BoolLit b -> Just (BoolLiteral b)

_ -> Nothing

We use the very handy pluck once again, in order to match against

the right kind of literal token, and pick out the data it contains. We then

make sure to wrap this data in the right kind of literal for our AST.

Int literals become IntLiteral i, strings StringLiteral s, bools BoolLiteral b,

as we went over before.

Parsing Operators

The next thing we’ll add support for is parsing operators. This requires a bit of thought before we get to writing out our parser though.

Operator Precedence

A first approach towards operators would be to treat them as a kind of punctuation. If you have something like:

x + y - a + 3

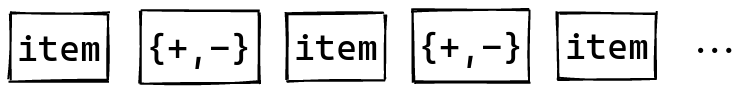

The names and literals are like words composing this arithmetic sentence, and the arithmetic operators are like the punctuation between the words. A first approach would start with some parser for these bottom level words. Then you’d use this parser, separated by the arithmetic tokens:

One problem with this approach is precedence. For example, multiplication with

* has higher precedence than addition with +. This means that an expression like:

1 + 2 * 3 + 3 * 5

should parse as:

((1 + (2 * 3)) + 3) * 5

and not:

((((1 + 2) * 3) + 3) * 5)

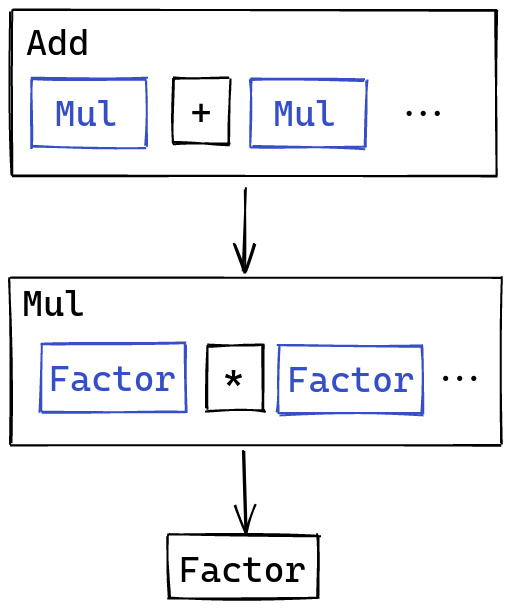

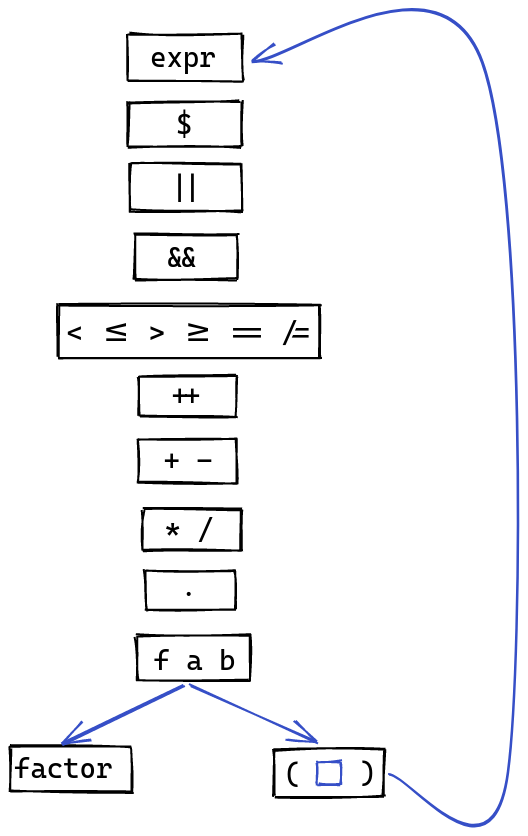

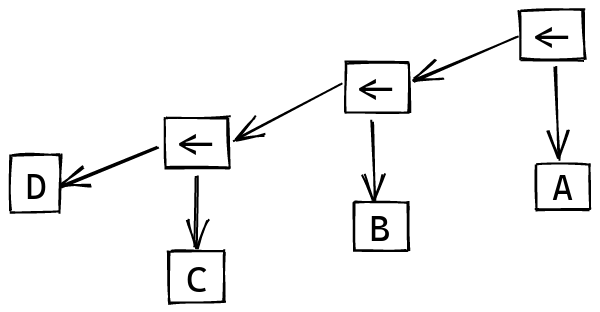

We would get the latter if we parsed addition and multiplication with the same precedence. One way to fix this is to introduce multiple layers, with one layer for each level of precedence:

Addition would parse multiplication, separated by +, and multiplication would

parse literal factors, separated by *. This paradigm allows us to skip

levels too. A single item like 3 falls under the “at least one number separated by *”

category: we just have the single number.

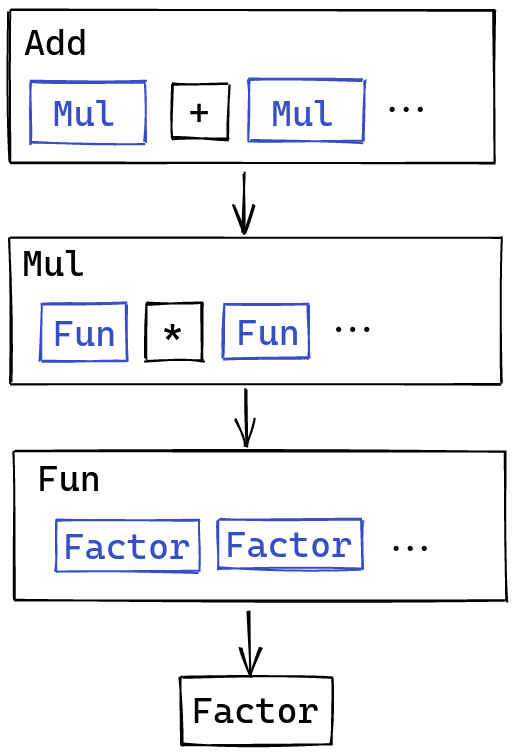

Function application falls under this paradigm as well. We can treate

function application as a very high precedence kind of operator. Instead of

parsing “at least one <sub-factor>, separated by <operator>”, we just parse

“at least two <sub-factor>s”. (This makes sure that,

only f x is considered as a function application, since f alone

would just be a name).

With multiplication, addition, and function application, our tower of operators now looks like this:

One aspect is missing though: parentheses! In languages with arithmetic expressions like these, you can manually insert parentheses to override the grouping rules.

For example, this expression:

(1 + 2) * 3

is not the same thing as:

1 + 2 * 3

precisely because the parentheses have been inserted.

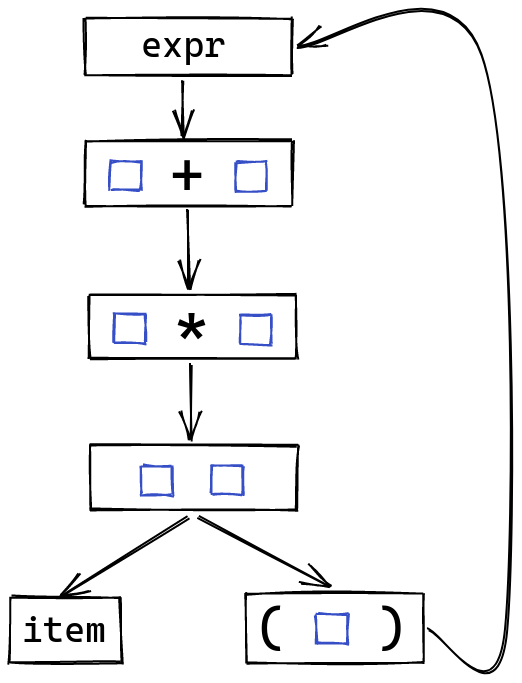

There’s a simple rule to make this work. Instead of having the bottom of our tower only have dead-end rules like literals, or simple names, we can instead add a rule that goes all the way to the top, parsing any expression surrounded with parentheses:

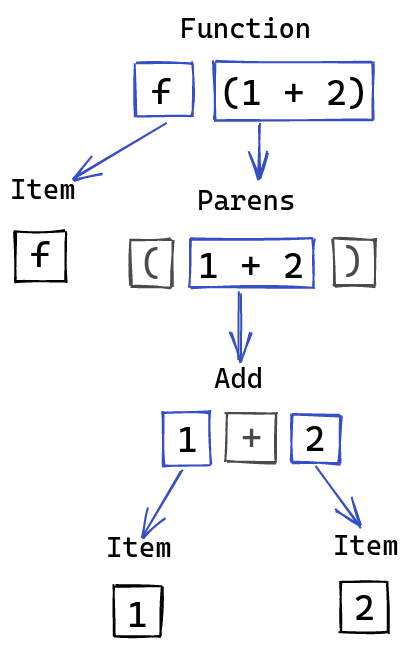

Parsing some expression like f (1 + 2) will work, because we end up with a transition

like this:

This is also useful beyond arithmetic, since we wanted to allow arbitrary expressions inside of parentheses anyways. As bizarre as it may seem, something like:

function (

case x of

1 -> 2

_ -> 3

)

is a valid bit of Haskell. This precedence looping trick will allow us to parse this kind of thing once we expand our expressions to accept more than just operators.

Using this approach, a full precedence tower including all of the operators in our language looks like this:

(See this link for a good overview of the precedence of different operators).

With that in mind, have enough thinking done to start implementing this precedence tower.

Operator Utilities

The parsing for each layer of operator will be very similar, so we can go ahead and define a handful of utilities we’ll be using to build them up.

The first utility is to take a parser for <item> and turn it

into a parser for ( <item> ). This is useful for implementing the looping

in our tower of precedence. This utility just requires matching

() tokens before and after the original parser:

parensed :: Parser a -> Parser a

parensed p = token OpenParens *> p <* token CloseParens

Here we use the convenient *> and <* operators:

(*>) :: Applicative f => f a -> f b -> f b

(<*) :: Applicative f => f a -> f b -> f a

These sequence their arguments in the same order as <*>, but pick a different

result. For our parensed parser, this does the right thing, parsing

the ( before our original parser, and the ) after, but leaving us with

just the original result.

When thinking about parsing operators, we had the nice of idea of doing something like “parse at least one factor, separated by an operator”. We can make a utility that does this:

sepBy1 :: Parser a -> Parser sep -> Parser [a]

Given a parser for a, and parser for sep, this creates a parser that

parses one or more occurrences of a, separated by sep. So,

something like sepBy1 literal (token Semicolon) would parse things like 3;1;"foo".

The implementation makes straightforward use of a few utilities for Alternative:

sepBy1 :: Parser a -> Parser sep -> Parser [a]

sepBy1 p sep = liftA2 (:) p (many (sep *> p))

Semantically, we first parse p, and then zero or more occurrences of

sep followed by p. So:

<p>

<p> <sep> <p>

<p> <sep> <p> <sep> <p>

are all going to be accepted by this parser.

many :: Alternative f => f a -> f [a] is provided to us, since parsers

implement the Alternative class.

We use sep *> p each time, since we just want the item parsed, and not the separator.

Finally, we use liftA2 (:) to cons the first item parsed, with the many items

produced by the rest of the parser.

Now, this would work for something simple like multiplication, since we

could parse out many multiplication factors, separated by *. One slight

problem is that some operators have the same precedence. For example,

+ and -. We need a modified version of sepBy1 where we remember

the separators we see. In fact, it would be even more useful

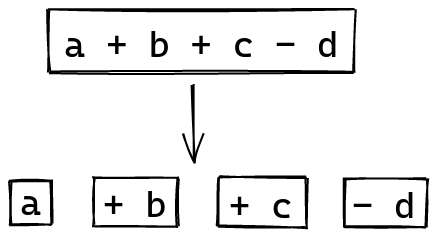

if given something like:

1 + 2 - 3 + 4

our parser could recognize this as:

1 (+, 2) (-, 3) (+, 4)

and then build up the correct parse tree, using each operator:

((1 + 2) - 3) + 4

This inspires the following type for parsing operators:

opsL :: Parser (a -> a -> a) -> Parser a -> Parser a

The first parser is used for separators, and the second parser is used

for the factors between separators. Semantically, this acts

like sepBy1, with the arguments reversed. The key difference is that

our separator parser produces a function used to combine the items

to its left and right. For example, for parsing addition and subtraction,

we could use this as our separator:

(BinExpr Add <$ token Plus) <|> (BinExpr Sub <$ token Dash)

If we see a +, we combine things as an addition expression, and if we see

a -, then we combine things with a subtraction expression.

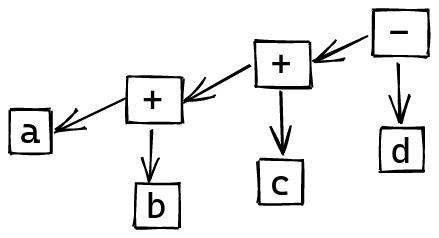

The implementation is similar to sepBy1

opsL :: Parser (a -> a -> a) -> Parser a -> Parser a

opsL sep p = liftA2 squash p (many (liftA2 (,) sep p))

where

squash = foldl' (\acc (combine, a) -> combine acc a)

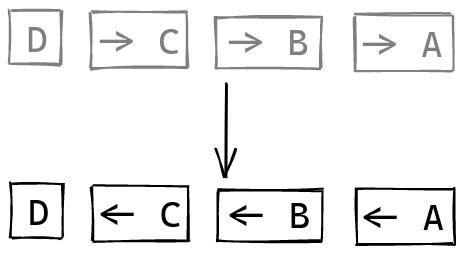

Instead of discarding the separators, we now keep them alongside the tokens:

Then, we fold from the left, using the combinator that’s now attached to each token we encounter:

In practice, this works out nicely. Given some arithmetic expression like:

a + b + c - d

this groups things in the way we’d expect:

((a + b) + c) - d

One problem is that this works for left associative operators, since we have our large expression on the left, and add items as we scan towards the right.

Some operators are not left associative though! For example,

the function arrow -> between types associates to the right:

For example, this snippet:

Int -> String -> Int

means:

Int -> (String -> Int)

and not:

(Int -> String) -> Int

We need to create an opsR function, that does the same thing as opsL,

but associates to the right instead:

opsR :: Parser (a -> a -> a) -> Parser a -> Parser a

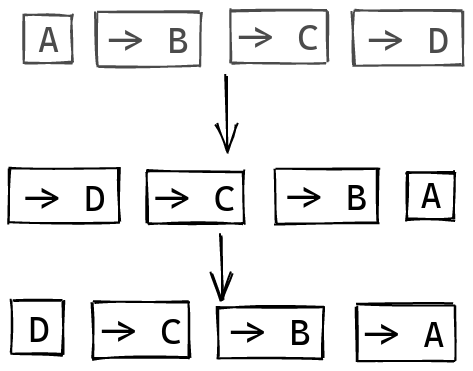

The idea is that given some sequence, like:

A -> B -> C -> D

We end up with:

after grouping the items and the separator, like we did in opsL.

Next, let’s flip this sequence around, before moving the separator to the right one step:

Now we also need to flip the operator, to make sure that the arguments are passed in the right order.

And then our scanning approach from last time works:

With this in mind, here’s the implementation of opsR:

opsR :: Parser (a -> a -> a) -> Parser a -> Parser a

opsR sep p = liftA2 squash p (many (liftA2 (,) sep p))

where

shift (oldStart, stack) (combine, a) =

(a, (combine, oldStart) : stack)

squash start annotated =

let (start', annotated') = foldl' shift (start, []) annotated

in foldl' (\acc (combine, a) -> combine a acc) start' annotated'

Our starting point is the same as with opsL, having parsed our

first item, and the following items along with their separators. From there,

we do a first scan, where we want to end up with each separator

attached to the item on its left, and the last item in our starting list

alone.

We do this with foldl', keeping track of the last item we’ve seen, and

the tail of items along with their new separators. When we see a new (sep, a)

pair, a becomes our new last item, and the previous item

is paired up with sep, and put onto the tail.

Finally, we can scan over this list as if we were doing a left associative

operator, with the caveat that we swap the arguments to combine.

This is because we need to apply flip combine in practice,

and not just combine, to accomplish the “operator flipping”

we went over in the previous diagram.

In practice, this means that if we have:

A -> B

which we’ve separated into:

(B, [(->, A)])

the -> function is still expecting the accumulator on its right,

to make, A -> B.

This took me a while to get a hold of as well, but thinking through the illustrations really helps make sense of how this operation works.

Operators in Practice

At the top of our precedence hierarchy, we have expressions:

expr :: Parser Expr

expr = binExpr

For now, all the expression we have are binary expressions. This is where we’ll have all of our operator parsing.

We have:

binExpr :: Parser Expr

binExpr = cashExpr

where

cashExpr = opsR (BinExpr Cash <$ token Dollar) orExpr

The lowest precedence operator is at the top:

the ubiquituous $, of course.

Next we have ||:

orExpr = opsR (BinExpr Or <$ token VBarVBar) andExpr

And then we have &&:

andExpr =

opsR (BinExpr And <$ token AmpersandAmpersand) comparisonExpr

Next we have comparisons, i.e. <, <=, >, >=, ==, /=:

comparisonExpr = opsL comparisonOperator concatExpr

where

comparisonOperator =

(BinExpr Less <$ token LeftAngle)

<|> (BinExpr LessEqual <$ token LeftAngleEqual)

<|> (BinExpr Greater <$ token RightAngle)

<|> (BinExpr GreaterEqual <$ token RightAngleEqual)

<|> (BinExpr EqualTo <$ token EqualEqual)

<|> (BinExpr NotEqualTo <$ token FSlashEqual)

Here we have different possibilities, since all of these operators have the same

precedence. For each of the possible tokens, we make sure to associate

the correct binary expression. Each operator parser

always yields exactly the combining function that it represents,

thanks to our use of <$.

Continuing on, we have ++, for string concatenation:

concatExpr = opsL (BinExpr Concat <$ token PlusPlus) addSubExpr

Followed by addition and subtraction with + and -:

addSubExpr = opsL addSubOperator mulDivExpr

where

addSubOperator =

(BinExpr Add <$ token Plus)

<|> (BinExpr Sub <$ token Dash)

Multiplication and division, with * and /, are a bit stronger:

mulDivExpr = opsL mulDivOperator composeExpr

where

mulDivOperator =

(BinExpr Mul <$ token Asterisk)

<|> (BinExpr Div <$ token FSlash)

And finally, the highest precedence binary operator is function composition with .:

composeExpr = opsR (BinExpr Compose <$ token Dot) unaryExpr

Next come unary operators, of which we only have -x, for integer negation.

Note that -(+1) 3 is valid haskell, and evaluates to -4. This still looks

a bit weird to me, but is pretty simple to handle:

unaryExpr :: Parser Expr

unaryExpr = negateExpr <|> appExpr

where

negateExpr = (token Dash *> appExpr) |> fmap NegateExpr

To parse a unary expression, we either find a - and a function application expression,

or just skip the - entirely.

appExpr is going to parse something like f a b c, and decide whether

or not it’s a function, based on how many things it sees:

appExpr :: Parser Expr

appExpr = some factor |> fmap extract

where

extract [] = error "appExpr: No elements produced after some"

extract [e] = e

extract (e : es) = ApplyExpr e es

If we see a single expression, then we leave that alone. Something like 3

by itself just means 3. If we see f 3, i.e. two or more items, then

the first of those items is a function, and the rest are its arguments.

And finally, we have factor, which is at the bottom of our precedence hierarchy:

factor :: Parser Expr

factor = littExpr <|> nameExpr <|> parensed expr

where

littExpr = fmap LitExpr literal

nameExpr = fmap NameExpr name

A factor is either a simple literal, a name, or it pulls off the beautiful trick we went over earlier: it expects some parentheses, and jumps all the way back to the top of the expression hierarchy!

Other Expressions

The next thing we’re going to tackle is parsing expressions that don’t contain

definitions, i.e. if, case and lambdas.

If expressions and lambdas are pretty simple, so let’s get them out of the way:

expr :: Parser Expr

expr = binExpr <|> ifExpr <|> lambdaExpr

where

For if, it’s pretty much what it says on the tin:

ifExpr =

IfExpr

<$> (token If *> expr)

<*> (token Then *> expr)

<*> (token Else *> expr)

We parse the condition after an if token, the first branch after

a then token, and the other branch after an else token. We use the standard

<$> and <*> operators to plumb these results into the IfExpr constructor,

which takes these three operands.

For lambdas, it’s also not that complicated. A lambda like:

\x y -> x + y

is just the \ token, some names, a -> token, and then an expression. In code,

we get:

lambdaExpr = token BSlash *>

liftA2 LambdaExpr (some valName) (token ThinArrow *> expr)

For case expressions, we first need a way to parse patterns. Parsing patterns is kind of similar to operators. We can have a constructor with simple arguments:

C 1 2 3 4

but in order to introduce more complicated patterns as arguments, we need parentheses:

C (A 2) 2 3 B

Notice how the B constructor takes no arguments,

and can appear without as a simple argument here.

Our definition for a single pattern looks like this:

onePattern :: Parser Pattern

onePattern = unspacedPattern <|> argfulPattern

where

argfulPattern =

liftA2 ConstructorPattern constructorName (some unspacedPattern)

A pattern is either a constructor taking some arguments, or a single

argument pattern. unspacedPattern will parse any kind of pattern that can

appear as an argument to a constructor, perhaps requiring parentheses:

unspacedPattern :: Parser Pattern

unspacedPattern = simplePattern <|> parensed onePattern

where

So, an unspacedPattern is either an entire pattern, wrapped in parentheses,

or a simple pattern, which can appear as an argument

without any parentheses:

simplePattern =

singleConstructor

<|> wildCardPattern

<|> varPattern

<|> litPattern

singleConstructor = fmap (`ConstructorPattern` []) constructorName

wildCardPattern = WildcardPattern <$ token Underscore

varPattern = fmap NamePattern valName

litPattern = fmap LiteralPattern literal

A pattern like this is either a constructor with no arguments, like

B in the example before, a wildcard pattern _, a single named

pattern, like x, or a literal, like 3 or "foo".

With patterns defined, we can start working on case expressions. Note that from the point of view of the parser, case expressions use braces and semicolons:

case x of {

1 -> 2;

_ -> 3

}

This kind of situation will appear with definitions as well, so we can go ahead and make a utility for parsing braces and semicolons:

braced :: Parser a -> Parser [a]

braced p =

token OpenBrace *> sepBy1 p (token Semicolon) <* token CloseBrace

braced turns a parser for a single item, into a parser for one or more items

separated by semicolons, all inside of braces.

We can then immediately used braced to create a parser for case expressions:

caseExpr :: Parser Expr

caseExpr =

liftA2 CaseExpr (token Case *> expr <* token Of) (braced patternDef)

where

patternDef = liftA2 (,) onePattern (token ThinArrow *> expr)

We have the case <scrutinee> of part, followed by the patterns,

which are in braces and semicolons. We than have the <pat> -> <branch>

part. Each pattern is just the

onePattern we defined before, followed by the -> token,

and the expression for that branch.

We could add this to the definition of expr, but we’re going to be

adding a few more expressions shortly, so we can just include it when

we get around to those.

Types

The remaining expressions are those related to definitions:

things like x = 2, or x :: Int. We can parse the expression part

of these value definitions just fine, but we haven’t added any parsing

for types yet! We’ll take care of this now, before moving

on to definitions.

Parsing types is going to be very similar to parsing patterns.

We have some types taking in arguments, like Pair Int String,

or List (List Int). We need to distinguish the types

that are basic enough to appear as arguments without parentheses,

like we did with patterns.

We’ll also need to add in a bit of operator parsing, to parse

function types like Int -> String -> Int.

Our goal is to define:

typeExpr :: Parser Type

which parses an arbitrary type.

Starting from the bottom, we have:

singleType :: Parser Type

singleType = fmap TVar typeVar <|> primType <|> parensed typeExpr

where

primType =

(IntT <$ token IntTypeName)

<|> (StringT <$ token StringTypeName)

<|> (BoolT <$ token BoolTypeName)

The singleType represents either a fundamental type that is not a kind of

custom type, or an arbitrary type, so long as it’s between parentheses.

We can then use this to define a full parser for type expressions:

typeExpr :: Parser Type

typeExpr = opsR ((:->) <$ token ThinArrow) baseType

where

baseType = singleType <|> customType

customType = liftA2 CustomType typeName (many typeArgument)

typeArgument :: Parser Type

typeArgument = namedType <|> singleType

where

namedType = fmap (`CustomType` []) typeName

We have different type “factors”, separated by the function arrow ->. This

becomes the constructor :->, representing the same thing in our syntax tree.

Of course, we make sure that we parse this operator in a right associative

way, so that:

Int -> String -> Int

is parsed as:

IntT :-> (StringT :-> IntT)

The base type that can appear between functions is either the single type

we defined earlier, or a custom type, which we excluded from the definition

of singleType. A custom type is parsed as some type name, followed by zero

or more arguments.

For the arguments, we do something interesting. We accept singleType, as

expected, but we also accept namedType. namedType is just a single

custom type, without any arguments. This allows us to have

a type like T as an argument, giving us something like Pair T T,

without needing to wrap T in parentheses.

Value Definitions

With that in place, we now have everything we need to parse value definitions. As a reminder, these look like:

x :: Int

x = 3

We have either a type annotation, or a name definition. The parser for this is pretty straightforward:

valueDefinition :: Parser ValueDefinition

valueDefinition = nameDefinition <|> typeAnnotation

where

nameDefinition =

NameDefinition

<$> valName

<*> many unspacedPattern

<*> (token Equal *> expr)

typeAnnotation =

liftA2 TypeAnnotation valName (token DoubleColon *> typeExpr)

A valueDefinition is either a nameDefinition, or a typeAnnotation.

A typeAnnotation is a name, followed by a :: and some type.

A nameDefinition is also a name, but this time with multiple patterns

as arguments, the = token, and then expression. We have multiple

patterns, since Haskell allows the syntax sugar:

f a b = a + b

for:

f = \a b -> a + b

These are unspacedPattern, since if we need complex patterns, we need them

to appear with parentheses. Something like:

f Pair a b =

will be parsed as:

f (Pair) (a) (b) =

instead of:

f (Pair a b) =

which requires explicit parentheses.

Remaining Expressions

With these value definitions in place, we’re now ready to finish defining all

of our expressions. The remaining expressions

we need to add to expr are where and let expressions:

expr :: Parser Expr

expr = notWhereExpr <|> whereExpr

where

notWhereExpr =

letExpr <|> ifExpr <|> lambdaExpr <|> binExpr <|> caseExpr

ifExpr =

IfExpr

<$> (token If *> expr)

<*> (token Then *> expr)

<*> (token Else *> expr)

lambdaExpr = token BSlash *>

liftA2 LambdaExpr (some valName) (token ThinArrow *> expr)

letExpr = liftA2 LetExpr

(token Let *> braced valueDefinition) (token In *> expr)

whereExpr = liftA2 WhereExpr

notWhereExpr (token Where *> braced valueDefinition)

It should be clear that notWhereExpr <|> whereExpr includes every

kind of expression, unless you’re a constructive mathematician.

For let expressions, we just parse the token let, followed by

some value definitions in braces and semicolons, the in token,

and then an expression.

Remember that let introduces a layout, so:

let

x :: Int

x = 2

in x

is lingo for:

let {

x :: Int;

x = 2

} in x

Now, for where expressions, it’s tempting to do something like:

expr *> token Where *> braced valueDefinition

but the problem is that this parser recurses infinitely. This is an issue we haven’t touched upon yet, called left recursion. This arises in theory for parsing methods like ours, and for parser combinators in particular, even in a lazy language like Haskell.

The fundamental problem is that if we have a rule like this,

to parse expr, we try parsing expr, which means that we try

to parse expr, and so we see if we can parse expr, and we give

a shot at parsing expr, and then, out of curiosity, see

if maybe parsing expr might work, etc.

We aren’t able to make any progress, because we have no concrete rules to latch on to.

The solution is to not have expr on the left here, but notWhereExpr

instead. This way, if our parser starts “exploring” this path, it can’t immediately

loop back onto itself, but instead has to parse a different rule

that will allow it to make progress.

This is why we define notWhereExpr to include everything except whereExpr,

to prevent this kind of immediate loop, with no tokens in between.

Anyhow, with this trick resolved, we have now finished parsing all of the expressions in our language. The end is in sight!

Other Definitions

The only remaining items to parse in our syntax tree are custom type definitions, and type synonyms, which make up the remaining kinds of definition in our language.

For type definitions, we’ll need a parser for each of the constructors that make up definitions like:

data VariantA = A Int String | B String Int

This gives us:

constructorDefinition :: Parser ConstructorDefinition

constructorDefinition =

liftA2 ConstructorDefinition constructorName (many typeArgument)

We can reuse the typeArgument we defined earlier, which was

used for the simple types that appear as arguments to a custom type,

like Pair Int (List String). Of course, if we have a constructor:

PairConstructor Int (List String)

then it’s natural to reuse the same parsing scheme for its arguments.

A constructor doesn’t necessarily have any arguments, hence the many,

instead of some.

Finally, we can use this to parse the remaining definitions:

definition :: Parser Definition

definition = valueDefinition' <|> dataDefinition <|> typeSynonym

where

valueDefinition' = fmap ValueDefinition valueDefinition

dataDefinition =

DataDefinition

<$> (token Data *> typeName)

<*> many typeVar

<*> (token Equal *> sepBy1 constructorDefinition (token VBar))

typeSynonym = liftA2 TypeSynonym

(token Type *> typeName) (token Equal *> typeExpr)

A definition is either a value definition, a data definition, or a type synonym.

Type synonyms are pretty simple. We have a type token, the

name of the synonym, and then =, followed by the type we’re making

an alias of.

For data definitions, we first have the data token, followed by the

name of the new custom type, and any type variables it might have.

We have then have an = token, followed by its constructors. There

must be one or more constructors, each of them separated by a | token.

And now we can parse all of the definitions in our language. We just have a bit of plumbing left to do to connect all of this together.

Gluing it all together

A Haskell program consists of a series of top level definitions. The whole file is actually in a braced environment, which means that we have the following parser for the entire AST:

ast :: Parser AST

ast = fmap AST (braced definition)

These definitions include both value definitions, so definition values by assigning them expressions, or annotating their types, as well as defining new types, through type synonyms, or data definitions.

We also need to amend our ParseError type to be a bit more informative:

data ParseError

= FailedParse

| AmbiguousParse [(AST, [Token])]

deriving (Show)

While still not as informative as you really would like, we now have two kinds of errors. The first occurrs if our parser found no way to parse the tokens given to us, and the second occurrs if multiple possible ASTs have been produced after going through all of the tokens.

I’ve mentioned ambiguity being a concern when designing some aspects of the parser, and avoiding this kind of error is the reasoning behind some of the design.

With these errors in mind, we can amend our parser function to use

the ast parser we just defined:

parser :: [Token] -> Either ParseError AST

parser input = case runParser ast input of

[] -> Left FailedParse

[(res, _)] -> Right res

tooMany -> Left (AmbiguousParse tooMany)

We use runParser :: Parser a -> [(a, [Token])] to get a list of parse results,

after running the parser for our entire syntax tree on the input tokens.

If we have no possible parses, then that’s the first error we defined above.

If we have too many parses, that’s the ambiguous error. Finally,

if we just have a single result, then that’s the AST that we want our parser to return.

And with that, we’ve finished our parser! It’s time to pat ourselves on the back, and try it out with a few examples.

Examples

If we run

cabal run haskell-in-haskell -- parse file.hs

we’ll be able to see the parse tree for a given source program.

For something simple like:

x :: Int

x = 2

we get:

AST

[ ValueDefinition

( TypeAnnotation "x" IntT )

, ValueDefinition

( NameDefinition "x" []

( LitExpr

( IntLiteral 2 )

)

)

]