(Un)fold as (Co)algebra

One cool thing about lists is that they have canonical ways of consuming and producing them: folds, and unfolds. It turns out that these are canonical, in that folding and unfolding functions are themselves isomorphic to lists. In this post, we’ll explore why this is true.

This post will build on a previous post I made a while back, so I’d recommend checking that out as well if this topic interests you.

Background Information

Our starting point is the standard definition of a list:

data [a] = a : [a] | []

This recursive definition says that a list is either empty, or an element prepended to a list. We also have the two fundamental fold and unfold operations:

foldr :: (a -> r -> r) -> r -> [a] -> r

unfoldr :: (r -> Maybe (a, r)) -> r -> [a]

There’s already some nice symmetry between the two, but there’s actually much more symmetry lying underneath this surface.

List as Fix Point

As usual in Haskell, you can decompose a recursive definition into a functor,

which isn’t recursive, and the “prototypical recursive type”: Fix

data Fix f = Fix (f (Fix f))

For the case of list, we have:

data L a r = Nil | Cons a r

type [a] = Fix (L a)

The r type in L a r represents the “recursive part”. By taking Fix of L a,

we end up with something that is not only isomorphic to [a], but structurally the

same thing. We have the exact same pattern of construction as the normal list.

Fix as Initial Algebra

Roughly speaking, for an endofunctor $F$, an “$F$-Algebra” is going to be a tuple:

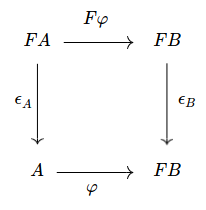

$$ (A, \epsilon_A : F A \to A) $$ consisting of an object, along with an evaluation function, from $F A$ to $A$. These algebras form a category, with morphisms being commutative diagrams like this:

These are morphisms $\varphi : A \to B$ which respect the structure of the algebra.

What we learned last time is that $\text{Fix} F$ is nothing more than a concrete representation of the initial object in this category. That is to say, there is a morphism $\text{Fix} F \to A$ for any other $F$-Algebra $A$.

Fix is Terminal CoAlgebra

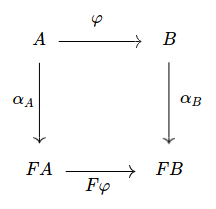

Similarly, for an endofunctor $F$, an “$F$-CoAlgebra” is going to be a tuple:

$$ (A, \alpha_A : A \to F A) $$

where $A$ is an object, and $\alpha_A$ is a morphism from $A$ to $F A$ in the category over which $F$ is an endofunctor. This form a category, once again, with structure preserving morphisms. The commutative diagram becomes:

Now, my claim is that by duality, $\text{Fix} F$ is going to be a concrete representation of the terminal object in this category. That is to say, there is a morphism $A \to \text{Fix} F$ for any $F$-CoAlgebra $A$.

I leave this without proof, because it seems somewhat natural that this would be true, it holds in practice in Haskell-land, and this post isn’t really about the Math anyways.

In Abstract Haskell

In Haskell, we can represent an $F$-Algebra a as:

(f a -> a)

A function f a -> a suffices to specify this specific algebra. To then say that Fix f

is initial, is to say there exists a function:

Fix f -> a

provided that a is an $F$-Algebra. Passing this fact explicitly, we have a function:

(f a -> a) -> Fix f -> a

Fix f -> (f a -> a) -> a

In fact:

Fix f = forall a. (f a -> a) -> a

This initiality property completely characterizes Fix f

For CoAlgebras, we represent them as functions:

(a -> f a)

The terminality of Fix f now means that there will be a function

a -> Fix f

provided that a is a CoAlgebra. That means that there is a function:

(a -> f a) -> a -> Fix f

In, fact, I claim that we have:

exists a. (a -> f a, a) = Fix f

For Lists

The two functions I want you to keep in mind are:

-- initiality

(f a -> a) -> Fix f -> a

-- terminality

(a -> f a) -> a -> Fix f

These must exist, and in fact completely characterize Fix f.

Now, for the case of [a], we have:

(L a r -> r) -> [a] -> r

(r -> L a r) -> r -> [a]

as our characteristic functions.

Now, if you look at the definition of L a r:

data L a r = Nil | Cons a r

You see that it is in fact isomorphic to Maybe (a, r).

This means that our terminality function is nothing more than:

(r -> Maybe (a, r)) -> r -> [a]

But this is nothing more than unfoldr!

Similarly, a consumer L a r -> r needs to provide a way to

handle both the Nil and the Cons cases. This means that

L a r -> r is isomorphic to (r, a -> r -> r).

But then we have:

(r, a -> r -> r) -> [a] -> r

(a -> r -> r) -> r -> [a] -> r

which is nothing more than foldr!

Concrete Isomorphisms

Concretely, we can create two data types to represent folds and unfolds:

data Fold a = Fold (forall r. (L a r -> r) -> r)

data Unfold a = forall r. Unfold r (r -> L a r)

The first data type, Fold encodes the characterization of [a] as the initial

object in the category of L-Algebras.

Unfold encodes the characterization of [a] as the terminal object in the category of

L-CoAlgebras.

Concretely, we’d like to prove the various isomorphisms between these objects

and [a]:

list2Fold :: [a] -> Fold a

fold2List :: Fold a -> [a]

list2Unfold :: [a] -> Unfold a

unfold2List :: Unfold a -> [a]

two of these are actually very easy, and quite elegant:

fold2List :: Fold a -> [a]

fold2List (Fold f) = f <| \case

Nil -> []

Cons a as -> a : as

list2Unfold :: [a] -> Unfold a

list2Unfold xs = Unfold xs <| \case

[] -> Nil

(a : as) -> Cons a as

I just find it amazing how strong the symmetry is between these two functions! It feels like you’re uncovering some kind of underlying beauty in the universe!

The other two are less elegant, but relatively straightforward:

list2Fold :: [a] -> Fold a

list2Fold [] = Fold (\eps -> eps Nil)

list2Fold (a : as) =

let Fold f = list2Fold as

in Fold (\eps -> eps (Cons a (f eps)))

unfold2List :: Unfold a -> [a]

unfold2List (Unfold r f) =

let go r' = case f r' of

Nil -> []

Cons a r'' -> a : go r''

in go r

Conclusion

These were just some rough notes about some insights I’ve had into

the duality of foldr and unfoldr, as well as their connection

with Algebras and CoAlgebras. Another point of exploration would be a

certain duality between foldl and foldr, but I’ll save that for another day.