Monty Hall and Counterfactuals

This is about some shower thoughts I had recently about the infamous Monty Hall problem. Namely, how to make sense of the counter-intuitive results involved. We’ll see how reasoning counterfactually can make the best strategy seem a lot clearer.

The Monty Hall Problem

Of course, a post about the Monty Hall problem wouldn’t be complete unless the author went through the trouble of restating the problem! So, here’s my shot at explaining it.

Our host, Monty, looks towards the audience, trying to find the next contestant. He raises his finger, and points straight at you! That’s right, you’re the next contestant for Monty’s fabulous game!

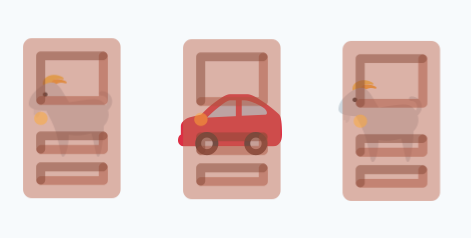

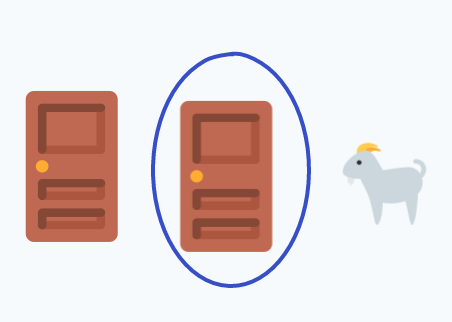

The rules are simple. There are three doors, behind one of which is a brand new car, and the other two, goats:

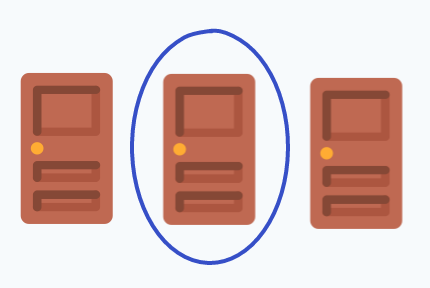

You don’t know which is which, of course, but the host directs you to pick one of them anyhows. For the sake of argument, let’s say you pick the middle one:

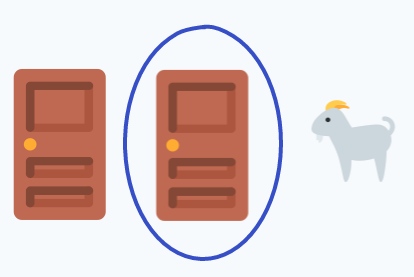

And here comes the twist: the Host reveals that one of the doors that you did not pick contains a goat:

Then the Host asks you whether or not you want to switch the door you’ve chosen, and move to the other door. The so called Monty Hall problem is thus: is it better in this situation to switch?

Intuitively it seems like there’s not much point in switching. We don’t know whether or not our current door has a car behind it, and there doesn’t seem to be a reason why the car should be behind the first door instead of the second, so why bother? It looks like we’re either or or off the car with equal probability at this point.

The problem is that this reasoning is actually wrong. In fact, switching here gives you a car $\frac{2}{3}$ of the time!

Many Worlds

Let’s go over some reasoning to see why this is the case.

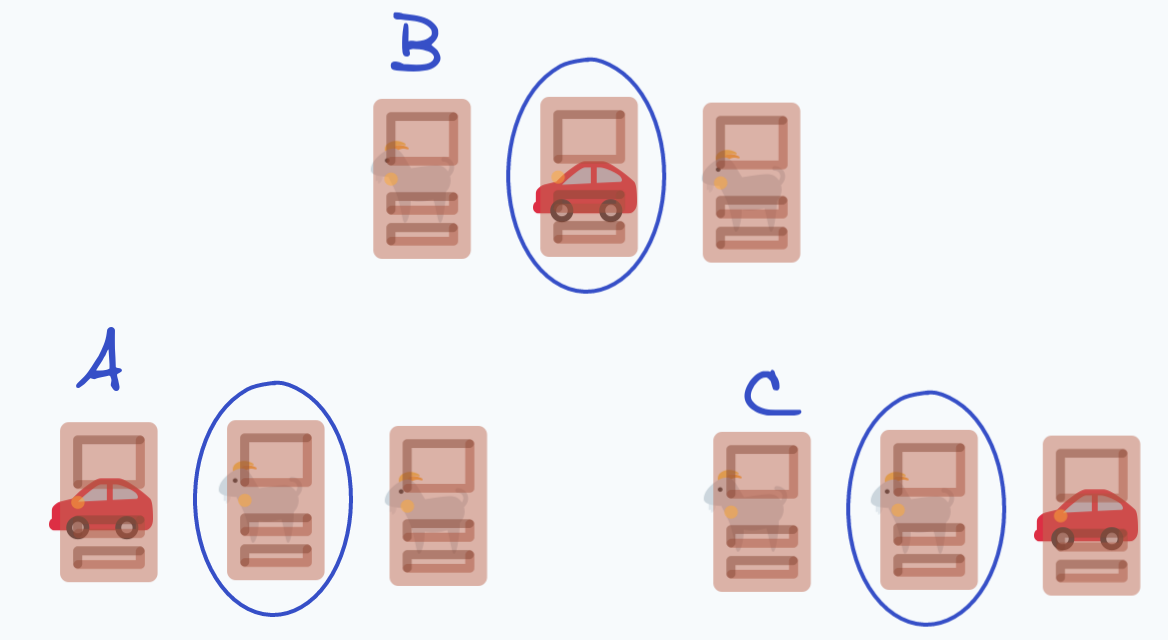

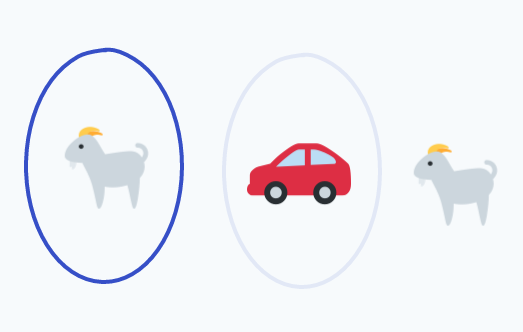

For the sake of this thought experiment, it doesn’t matter which door we pick, so let’s say we always pick the middle one. At this point, we can be in one of three states:

The car is either behind the first, second, or third door. I’ll denote these states $A, B$ and $C$ respectively.

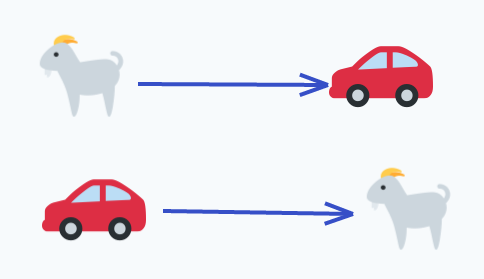

The interesting part about this is that what the Host does after we end up in one of these states doesn’t actually matter. The host will only ever reveal a door that we haven’t selected, and that doesn’t contain a car. Because of this, switching only benefits us whenever we’ve selected a goat:

Furthermore, looking at the different states we can be in, we see that we have a goat in states ${A, C}$. Therefore, if we’re in either of these states, and we switch, we end up winning the car! This gives us odds of $\frac{2}{3}$ in favor of switching, as mentioned earlier.

Committing

To make this even clearer, imagine that instead of being given the option to switch mid-game, let’s say that we know the rules of the game going, that the Host will reveal a goat, etc. In this hypothetical version, we have to commit to switching before the game even starts. We declare that we’re going to switch, or not going to switch, and then have to stick to that decision after the host reveals the actual contents behind a given door.

Looking at the game this way, should we pre-commit to switching? Clearly, given we don’t know whether or not we’re in state $A, B$ or $C$, it makes sense to commit to switching, since that strategy will give us a win in $2$ out of $3$ states.

So given that the Host’s reveal doesn’t actually change this fact, it seems somewhat clear that switching is a good idea, even if it seems to not matter by the time the choice actually takes effect.

Does it matter though?

Let’s say that you’re somewhat convinced, but still have some doubts about this reasoning. One line of objection is that sure, counterfactually, it seems like a good idea to pre-commit to switching, but let’s say we’ve picked the middle door, and then the host has shown us a goat behind the right door:

You might be convinced that committing to switching makes sense as a strategy to maximize our chances of winning, but does it really matter if we’ve made it to this situation?

As an even more striking example, let’s say that we’re at the very end of the game, we’ve switched to the left door, and the game looks like this:

Sure, switching gives us a $\frac{2}{3}$ advantage, from the beginning, but at this point we know what’s behind each door, and knowing that we played well from the beginning doesn’t change the fact that we’ve lost.

You might make a similar argument, saying that although there’s a $\frac{2}{3}$ tilt towards committing to switching, by the time the Host has revealed the goat on the right, this advantage is already immaterial.

Getting our hands dirty

To get past this reasoning, it’s best if we move up a level in formality, and actually try to manipulate some equations talking about what exactly’s going on here.

Let $G_R$ denote the event that the Host reveals a Goat behind the door on the right.

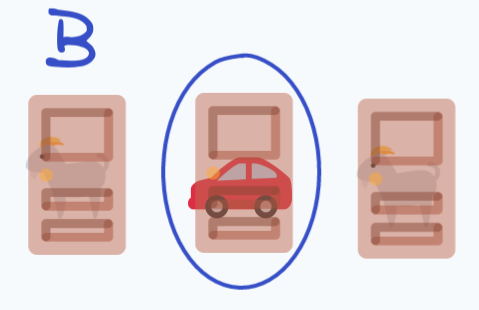

Now, denote by $C_M$ the event that the car turns out to be in the middle. In this case, switching to the other door would mean losing. Note that this corresponds exactly to state $B$:

We might as well just call this event $B$, then. Now, we know that $P(B) = \frac{1}{3}$. We’ve made the assumption that the car has no bias to be behind a given door, and we’re keeping that here. What we’re interested in, however, is not what $P(B)$ is, but rather:

$$ P(B | G_R) $$

i.e. how likely is there to be a car in the middle given that the Host has revealed a Goat behind the right door. The previous objections amount to saying that $P(B) \neq P(B | G_R)$, and that $P(B | G_R)$ makes it so that switching isn’t worth it, with $P(B | G_R) \geq \frac{1}{2}$. With $P(B) = \frac{1}{3}$, it’s obviously a good idea to switch knowing that alone.

Baye’s ubiquitous rule gives us:

$$ P(B|G_R) = \frac{P(G_R | B)P(B)}{P(G_R)} $$

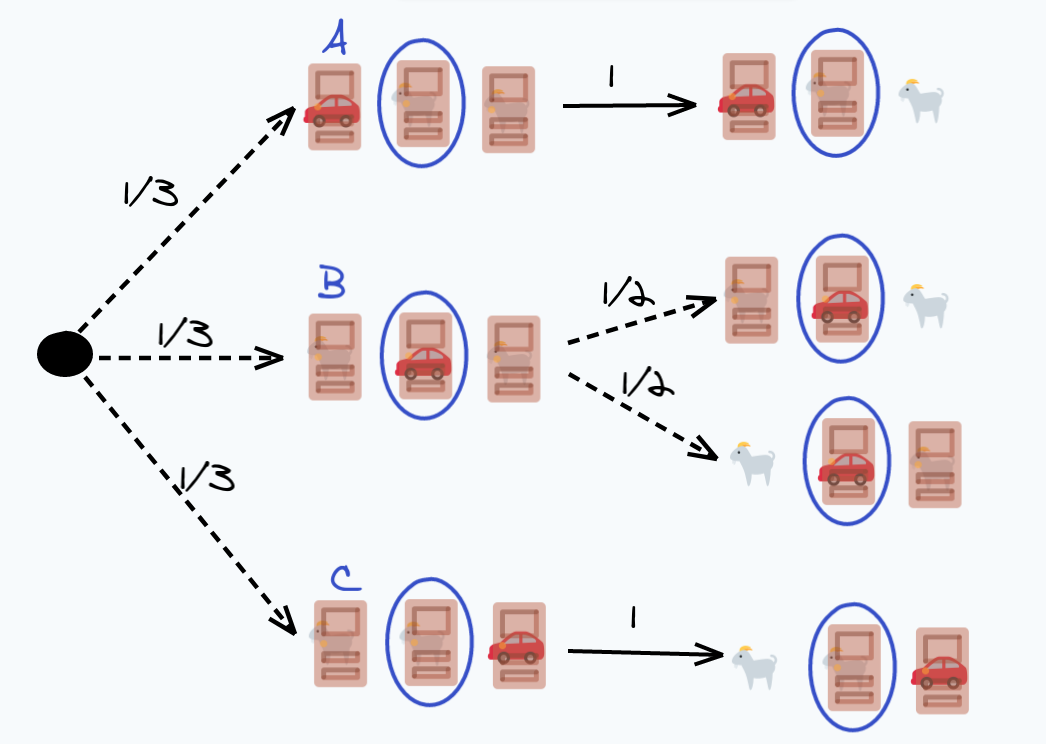

Now, let’s explore what $P(G_R)$ is through a decision tree:

This might seem a bit heavy at first, but the idea is simple. Each arrow is annotated with the probability of events moving in that direction. As explained earlier, the three starting positions of the car are equiprobable. We either have the car behind the first, second, or third door.

Now, the actions of the Host are actually quite constrained. They must reveal a goat, and they obviously can’t reveal what’s behind the door we’ve chosen.

With this in my mind, if we’re in situation $A$, then the host has no choice but to reveal a goat on the right. They can’t reveal the goat behind our door, and they can’t reveal the car on the left either.

In situation $C$, the opposite happens, the host is forced to reveal the goat on the left this time.

And in situation $B$, the host actually has a choice to make. Since the car is behind our door, the host can reveal either the left goat, or the right goat. We make the assumption that the host has no reason to prefer one door or the other.

So, to calculate $P(G_R)$, we just tally up all the leaf nodes where the goat is revealed on the right, weighted by the probabilities. This gives us:

$$ \frac{1}{3} \cdot 1 + \frac{1}{3} \cdot \frac{1}{2} = \frac{3}{6} = \frac{1}{2} $$

Furthermore, we’ve also calculated $P(G_R|B)$ in passing, as $\frac{1}{2}$. This is one of the annotated arrows in the center. We can combine all of this to get:

$$ P(B | G_R) = \frac{P(G_R | B)P(B)}{P(G_R)} = \frac{1 / 2 \cdot 1 / 3}{1 / 2} = \frac{1}{3} $$

So, even after revealing the goat on the right, there’s still only a $\frac{1}{3}$ chance that we’re sitting on the car, so we’re better off switching. We can apply a symmetric form of reasoning for if there were a goat on the left as well.

Conclusion

The Monty Hall problem is a classic, and probably features in every single Probability 101 class, or equivalent. It’s a great example of a somewhat counter-intuitive result, that we can untangle through clever reframing, or well-posed equations.

I’m most definitely not the first person to go over the problem, but after knowing the solution to the problem, but still getting stumbling over my own feet while thinking about it the other day, I wanted to put pen to paper and solidify my thinking.