Monomorphisms vs Epimorphisms

The concepts of monomorphism and epimorphism are very important in Category Theory. I always had a hard time remembering which one was which until I thought about a good mnemonic.

Put briefly, a monomorphism is the generalization of the concept of an injective function, and an epimorphism is the generalization of the concept of a surjective morphism. Monomorphisms and Epimorphisms are very important in Category Theory. Whenever you have a category where multiple paths or morphisms can exist between objects, it’s usually interesting to ask what these special morphisms correspond to.

In the familiar category $\mathcal{Set}$ of sets and functions, monomorphisms are injective, and epimorphisms are surjective, as we started off with.

But in an arbitrary category, these may not be the case, even if we’re working with structured sets. In the category of rings, for example, $\mathbb{Z}$ is initial, which allows us to have epimorphisms despite the possibility of those not being surjective (take $\mathbb{Z} \to \mathbb{Q}$).

Formally

Let’s just get the formal definition out of the way, so we can base our intuition off of it.

A monomorphism $f$ is a morphism such that post-composition preserves equality:

$$ \forall \alpha, \beta. \quad \alpha ; f = \beta ; f \implies \alpha = \beta $$

Dually, an epimorphism $f$ is a morphisms such that pre-composition preserves equality.

$$ \forall \alpha, \beta. \quad f ; \alpha = f ; \beta \implies \alpha = \beta $$

Note: I use the terms post and pre composition instead of left or right composition, as I believe in free interchange of forward ($;$) and backwards ($\circ$) composition of functions, and the terms left and right are not invariant, while post and pre are.

Now, at this stage, we could go through some kind of proof as to why these notions faithfully and fully capture the notion of injective and surjective functions on sets, but I’ll delay that a bit, to get a bit more of an idea of what these definitions mean, and how to remember them

Visually

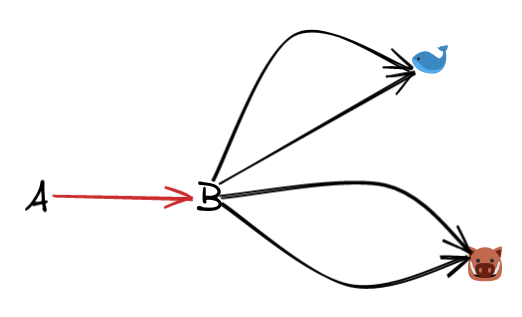

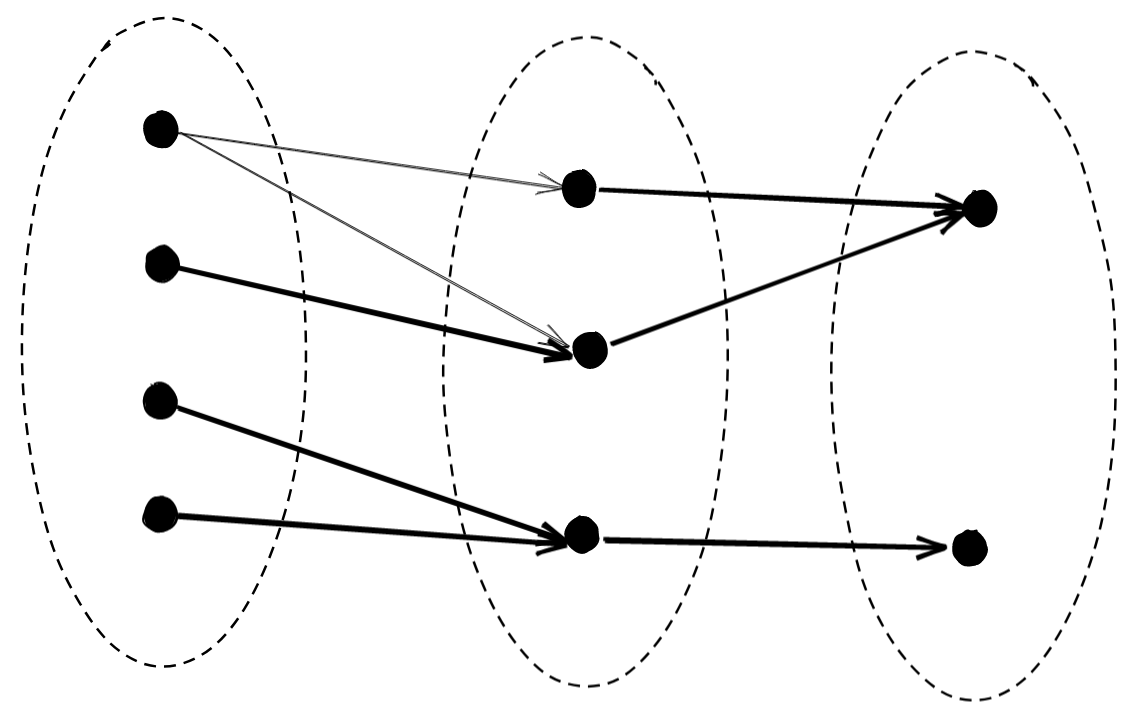

Let’s say we have some epimorphism from $A \to B$, along with other morphisms going outwards from $B$.

(I like thinking of epimorphisms as red, and monorphisms as blue, as we’ll see later)

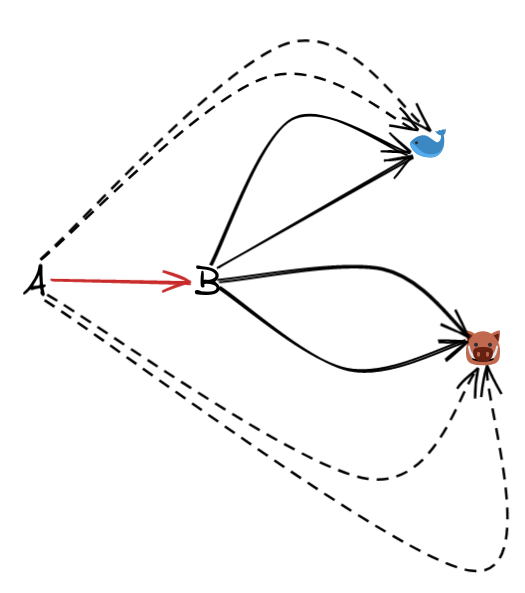

We can pre-compose with the epimorphism to induce the following:

So in some sense, we have a mapping from the morphisms in the inner diagram to the morphisms in the outer diagram. Roughly speaking, an epimorphism must induce an injective mapping between these diagrams.

For each morphism in the inner part, we have a corresponding morphism in the outer part, and distinct inner bits yield distinct outer bits.

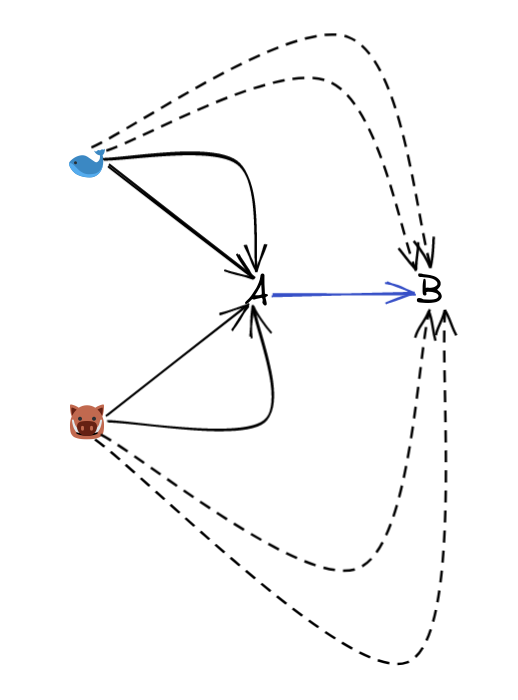

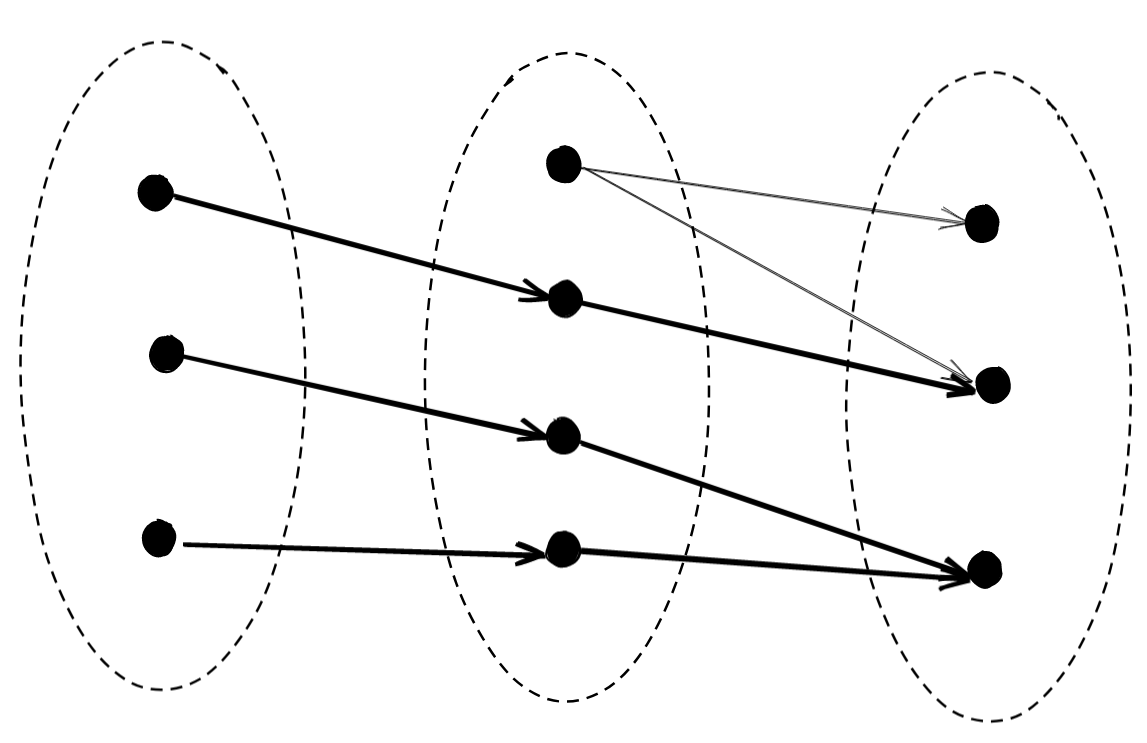

The idea with monomorphisms is the same:

Remembering

So these aren’t exceedingly difficult concepts, but they’re easy to confuse. I am incapable of not confusing the two after a day. Literally, I’ve had to prove which one was which at least 3 times in the past week, and I developed this trick the second time, which is what I’m going to focus on in the rest of the past.

My starting point is to remember that monomorphisms are injective, and epimorphisms are surjective (on sets). I don’t have any mnemonics for this, but I don’t find myself forgetting this part.

I also remember the part about composition on one side preserving equality.

The part I don’t remember well is whether monomorphisms get post-composition or pre-composition. Ditto for epimorphisms.

So the trick, if you can call it that, is to be able to rederive that fact that post-composition with injective functions preserves equality, and pre-composition with surjective functions preserves equality.

What does it even mean for two functions to not be equal?

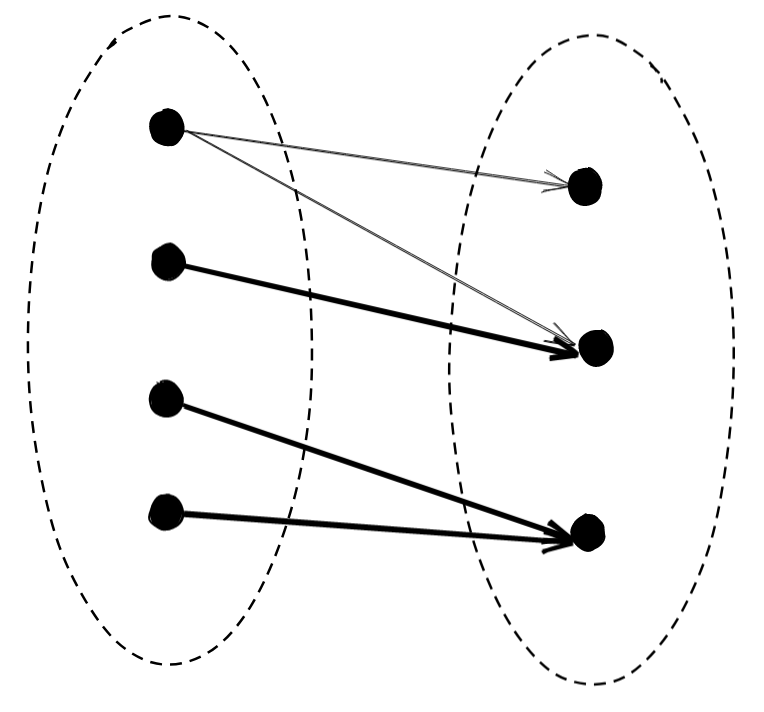

At a minimum, it means that there’s a single point where they diverge:

Here I use the thick arrows to represent points where the two functions agree, i.e. are equal, and the thin arrows to represent the disagreeing mappings at points where they’re unequal. Functions are equal (in the context of sets), simply if they agree on every point of their domain.

The Game

To remember whether injective or surjective functions are the ones where post-composition reveals equality, I play a simple game: given two unequal functions, how can I hide this fact through post-composition? I’ll have to give up on one of the definining properties of injective or surjective functions. Either I’ll have to map two distinct points to the same point, or not cover the entire range.

So, how do we had the discrepancy at the top point?

Simple. We just map the two places where the arrows diverge to the same point later:

Now if we look at the whole diagram, we don’t see any points where the two outer functions disagree, it looks as if they’re equal, even though internally there’s a point where they disagree. We fix this by mapping those two points down to the same one. Of course, to do this, we need to sacrifice on injectivity.

Hence, to preserve equality through post-composition:

$$ \alpha ; f = \beta ; f \implies \alpha = \beta $$

we must have an injective function, otherwise it might be possible to find two functions with a discrepancy that gets hidden by our non injective function.

At this point, we instantly get that pre-composition belongs to epimorphisms / surjective functions, since that’s the other side of the coin. This is the neat thing about duality eh.

We can explicitly go through this game again though.

How do we hide the discrepancy through pre-composition?

Simple. We just don’t reach the point that’s a problem!

We can hide the discrepancy by not covering all the points in our range, and thus never encountering the problem.

Thus, if we don’t have a surjective function, it’s possible to mistake two unequal functions for equal after pre-composition. Thus, pre-composition corresponds to surjective functions, and thus epimorphisms more generally.

And that’s all there is to it. Armed with this knowledge, it should be easy to rederive which is which whenever you forget!

Inverses

Sometimes you might see injective and surjective characterised in terms of the existence of certain inverse functions. This isn’t as general as the notion of monomorphism and epimorphism we developed earlier, but it’s easy to remember how things work out.

A morphism that has a post-inverse i.e. a morphism $f^{-1}$ such that

$$ f ; f^{-1} = 1 $$

is a monomorphism (where $1$ is the identity morphism, $1 ; g = g ; 1$ for every function $g$)

Dually, epimorphisms arise from morphisms with a pre-inverses, i.e. a morphism $f^{-1}$ such that

$$ f^{-1} ; f = 1 $$

Now, monomorphisms and epimorphisms don’t necessarily have inverses like this, in a general category. But, whenever a morphism with such an inverse exists, it’s always a monomorphism or an epimorphism.

So, how do you remember which is which?

This one is pretty easy, if you can remember that post-composition “belongs to” monomorphisms, it’s natural that having a post-inverse gives you a monomorphism. Ditto with epimorphisms, pre-composition, and pre-inverse.

Remember that monomorphisms have the equation:

$$ \alpha ; f = \beta ; f \implies \alpha = \beta $$

Well, if have have a post-inverse, we can simply use that to arrive at the conclusion

$$ \alpha ; f = \beta ; f \implies \alpha ; f ; f^{-1} = \beta ; f ; f^{-1} \implies \alpha ; 1 = \beta ; 1 \implies \alpha = \beta $$

And for an epimorphism, we can do the dual thing:

$$ f ; \alpha = f ; \beta \implies f^{-1} ; f ; \alpha = f^{-1} ; f ; \beta \implies 1 ; \alpha = 1 ; \beta \implies \alpha = \beta $$

So, if you just remember which equation (post or pre) belongs to mono or epi morphisms, then you can remember whether post or pre inverses give rise to mono or epi-morphisms.

If all that was not useful, just memorize:

mono, injective, post-composition, post-inverse

epi, surjective, pre-composition, pre-inverse

I prefer holding on to the derivation, since understanding why these connections exist is more important than knowing that they exist, for the most part.