On Formalizing Security Games

Games

A game $G$ of class $\mathfrak{c}$ with $N$ phases consists of

- Query types $Q_1, \ldots, Q_n : \mathcal{U}$

- Response types $R_0, \ldots, R_n : \mathcal{U}$

- State types $C_0, \dots, C_{N + 1} : \mathcal{U}$

- A starting state $c_0 : C_{0}$

- Transition functions (of class $\mathfrak{c}$): $$ \begin{aligned} &\mathscr{C_0} : C_0 \xrightarrow{\mathfrak{c}} C_1 \times R_0\cr &\mathscr{C_i} : C_i \times Q_i \xrightarrow{\mathfrak{c}} C_{i + 1} \times R_i \end{aligned} $$

The notion of “class” is just a way to talk about various assumptions around the functions we use. In most cases, $\mathfrak{c}$ will be randomized functions, that are efficiently computable (i.e. $\mathcal{O}(\lambda^d)$). Talking about a class of functions is a good way to sweep all of our theoretical concerns about modelling computation under the rug. We can easily describe our class of functions using lambda calculus, generalized recursive functions, Turing machines, etc.

While perhaps obtuse at first, this actually matches the vague way games are usually defined. For example, the semantic security game:

$$ \begin{aligned} &k \xleftarrow{R} \mathcal{K} &&\cr && \xleftarrow{m_0, m_1} &\cr &b \xleftarrow{R} \{0, 1\} &&\cr &c \longleftarrow E(k, m_b) &&\cr && \xrightarrow{c}\cr && \xleftarrow{\hat{b}} &\cr \end{aligned} $$

This notation implicitly fits this paradigm. We send and receive messages, with a bit of randomized computation in between. The reason we have multiple states is mainly to reflect that fact that we have a “memory” between different phases. In most cases, each state type will encompass the previous ones: $C_i \subseteq C_{i + 1}$, reflecting the fact that we retain memory of previously defined variables.

Sometimes, we are required to send a message by the formalism, but have nothing interesting to say, such as at the beginning of the previous protocol. This is reflected with a message type of $\{\bullet\}$, which can implicitly be omitted.

Because of this, a game with $N$ phases can always be extended to a game with $M \geq N$ phases, simply by sending trivial messages and having trivial states in $\{\bullet\}$. We thus take no qualm as considering all games to have some polynomially bounded number of phases $N$.

Adversaries

An adversary $\mathscr{A}$ of class $\mathfrak{c}$ for $G$ consists of

- State types $A_0, \ldots, A_N : \mathcal{U}$

- A starting state $a_0 : A_0$

- Transition functions (of class $\mathfrak{c}$): $$ \mathscr{A_i} : A_i \times R_i \xrightarrow{\mathfrak{c}} A_{i + 1} \times Q_{i + 1} $$

Note that the parameters here are dictated by the game, whereas the class of adversaries isn’t. We can have adversaries that aren’t polynomially bounded, although most games won’t be secure against that strength.

An adversary together with a game as an explicit model for the implicit syntax of game commonly used, which is what I like about this formalism.

Morphisms of Games

A morphism $G \to G'$ between games of class $\mathfrak{c}$ with $N$ phases consists of

- Helper types $H^0_0, H^1_0, \ldots, H^0_N, H^1_N : \mathcal{U}$

- functions of class $\mathfrak{c}$

$$ f^0_i : H^0_i \times R'_i \xrightarrow{\mathfrak{c}} H^1_i \times R_i $$

$$ f_i^1 : H_i^1 \times Q_i \xrightarrow{\mathfrak{c}} H_{i+1}^0 \times Q'_{i+1} $$

For any adversary of $G$, this creates an adversary of $G'$, via:

$$A'_i := H_i^0 \times A_i$$

$$ \begin{aligned} &\mathscr{A'_i} : A'_i \times R'_i \xrightarrow{\mathfrak{c}} A^{\prime}_{i+1} \times Q'_{i+1}\cr &\mathscr{A'_i}((h^0_i, a_i), r'_i) :=\cr &(h^1_i, r_i) \leftarrow f_i^0(h^0_i, r'_i) \cr &(a_{i+1}, q_{i+1}) \leftarrow \mathscr{A_i}(a_i, r_i) \cr &(h_{i+1}^0, q'_{i+1}) \leftarrow f^1_1(h^1_i, q_{i+1})\cr &((h^0_{i+1}, a_{i+1}), q'_{i+1}) \end{aligned} $$

Essentially, even though a morphism is specified with a few small working parts, we immediately get a function which turns any adversary of $G$ into an adversary of $G'$. Note that this works regardless of the conditions imposed on the initial adversary. Naturally, if we want $\mathscr{A'}$ to be efficient, then $\mathscr{A}$ needs to be efficient as well. If $\mathscr{A}$ is randomized, then $\mathscr{A'}$ is necessarily randomized as well.

Once again, the implicit notation we use in informal security games is accurately modeled by this formalism. This models the common situation where we create a new adversary by “wrapping” another adversary. We massage their queries into a new form, and massage the responses into a new form as well. At each point, we’re allowed to do some computation, and to hold some intermediate state of our own.

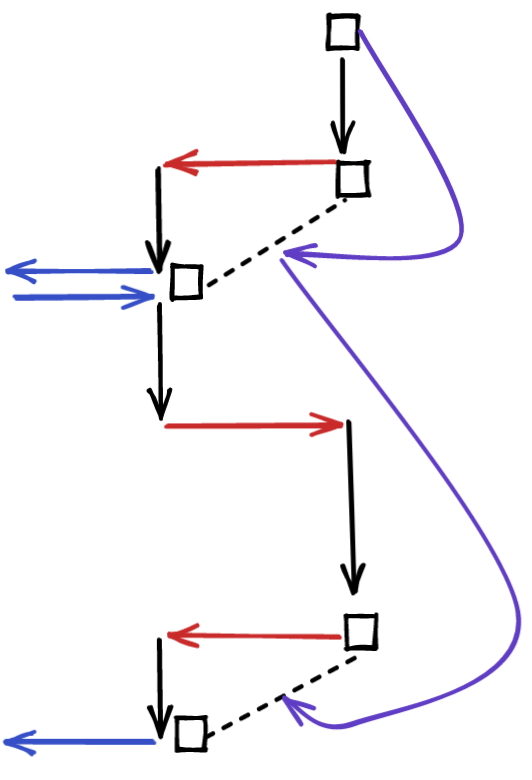

Diagrammatically, this looks like this:

Category of Games

One slight issue with the notion of morphism we have so far is that it encompasses many morphisms which are effectively the same. For example, if we add dummy variables to the helper states, the outcome of our wrapper is the same, yet it is technically different.

To amend this, we consider two morphisms to be equivalent if the responses and queries produced by $f^0_i$ and $f^1_i$ are the same between both morphisms.

The identity morphism has no helper states, and simply forwarding the queries and responses without any change.

To compose morphisms $f$ and $g$ with states $H_i^b$ and $K_i^b$, our states become the product $H_i^b \times K_i^b$. This immediately suggests the following composition rule:

$$ \begin{aligned} &(g^0_i \circ f^0_i)((h, k), r'') :=\cr &(k_2, r') \leftarrow g^0_i(k, r'')\cr &(h_2, r) \leftarrow f^0_i(h, r')\cr &((h_2, k_2), r) \end{aligned} $$

$$ \begin{aligned} &(g^1_i \circ f^1_i)((h, k), q) :=\cr &(h_2, q') \leftarrow f^1_i(h, q)\cr &(k_2, q'') \leftarrow g^1_i(k, q')\cr &((h_2, k_2), q'') \end{aligned} $$

It’s relatively clear, although I haven’t gone through the pain of proving it, that this composition rules along with the identity morphism satisfy the appropriate rules for a category.

Let’s call this $\text{Game}$.

Category of Security Games

We need to augment games with a notion of “winning”. To do this, we have a function $\text{Adv} : P(C_{N + 1}) \to [0, 1]$, which takes a probability distribution over the final state, and returns an advantage in $[0, 1]$.

Given a game $G$ and an adversary for that game $\mathscr{A}$, of a common class $\mathfrak{c}$, it’s clear that we have a function $A_0 \times C_0 \xrightarrow{\mathfrak{c}} C_{N + 1}$, given by composing the transition functions of the challenger and the adversary together. Since the class functions is potentially randomized, we can run it over $(a_0, c_0)$, and arrive at a probability distribution over the result $C_{n + 1}$. In order to define the advantage of this adversary, we use this function $\text{Adv}$ over the resulting distribution. As a short-hand for this process, we write:

$$ \text{Adv}[G, \mathscr{A}] $$

In practice, $\text{Adv}$ is going to be very simple. Usually, it will of the form $|P[\text{Win}] - t|$, but we can consider more complicated things.

Such augmented games might be called “Security Games”.

We say that a game $G$ has security $\mathfrak{c}$, if for all adversaries $\mathscr{A}$ of class $\mathfrak{c}$, $\text{Adv}[G, \mathscr{A}]$ is a negligible function of some security parameter related to the class. In the usual case, we have the class of randomized computable functions with polynomial runtime in $\lambda$. This is commonly referred to as “computational security”. We also have “statistical security”, which considers adversaries that are unbounded in their runtime.

Morphisms are morphisms of games $G \to G'$, with the additional condition that for every adversary $\mathscr{A}$ of $G$, the induced adversary $\mathscr{A'}$ of $G'$ has an advantage at least as large, up to a polynomial factor:

$$ p(\lambda)\text{Adv}[G', \mathscr{A'}] \geq \text{Adv}[G, \mathscr{A}] $$

Here, $\p$ is a polynomial function of the ambient security parameter $\lambda$. Since we’re talking about games of class $\mathfrak{c}$, we already have an ambient security parameter, since we can talk about the efficency of the challenger.

This condition works well with composition, and naturally includes the identity morphism we’ve seen previously. The polynomial factor loosens the restrictions, while still making it so that if $\text{Adv}[G', \mathscr{A'}]$ is negligible, then so is $\text{Adv}[G, \mathscr{A}]$ is as well.

We call such a morphism a “reduction”.

This condition is actually necessary. In practice, most games are reasonably defined, and a morphism usually has a trivial proof of “advantage growth”. Unfortunately, some games are defined in a stupid way. For example, you can have a game in which only trivial messages are exchanged, and yet $\text{Win}$ always returns $0$. There’s a trivial morphism of games, and yet, no matter what the advantage of the adversary for the original game is, the advantage for this trivial game remains $0$. Because of this, in general we need to impose the restriction of advantage growth to define reductions.

The reason we allow for the negligible factor is to allow for games with negligible differences to be considered isomorphic.

Let’s call the category of security games and their reductions $\text{SecGame}$

Free-Forgetful Adjunction

There’s evidently a forgetful functor $? : \text{SecGame} \Rightarrow \text{Game}$, by stripping away the elements related to advantage.

It also seems that there’s a free functor $F : \text{Game} \Rightarrow \text{SecGame}$.

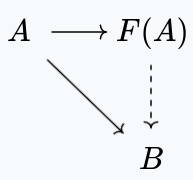

Now, the standard situation for such a functor would be:

i.e. we have a morphism $A \to F(A)$, such that for each morphism $A \to B$, we have a reduction $F(A) \to B$.

Now, the obvious choice for $F(A)$ is to use the same game, and pick the advantage elements in a judicious way. We can clearly use the morphism $A \to B$ for a morphism $F(A) \to B$. We just need to make sure that the advantage grows. A simple way to guarantee this is to make the advantage of $F(A)$ to be $0$, no matter what.

Thus, like in the trivial game, for $F(A)$. $\text{Adv}$ always returns $0$, with

Applications

Tensor Product of games

Given two games $G$, $G'$, you can define the tensor product $G \otimes G'$, by using states $C_i \times C_i'$, queries $Q_i \times Q_i'$, $R_i \times R_i'$, and transition functions $\mathscr{C}_i \times \mathscr{C'}_i$.

This represents parallel composition of games. An adversary has to play both games simultaneously.

The natural advantage definition here is to define $\text{Adv}_\times = \min(\text{Adv}, \text{Adv}')$. This is well defined, because we have a distribution over $C_{n + 1} \times C'_{n + 1}$, resulting in individual distributions for each part, where we can use the individual advantages.

This makes it so that if the adversary has a negligible advantage in one of the games, then they have a negligible advantage in this game as well.

I suspect, but have yet to prove, that there’s a symmetric monoidal structure on this category, using the tensor product of games, and the trivial game as unit.

Oracles

Given a function $f : \mathcal{Q} \to \mathcal{R}$, we’d like to model an Oracle implementing this function as a kind of Game, so that it fits into our definition.

We start with a two phase game:

$$ \begin{aligned} &q \xleftarrow{R} \mathcal{Q} &&\cr && \xrightarrow{q} &\cr && \xleftarrow{r \in \mathcal{R}} &\cr \end{aligned} $$

Now, here’s a bit of a technical point, we define $\text{Adv} := P[f(q) = r] \stackrel{?}{=} 1$, This means that adversaries have zero advantage unless they can answer all queries. This lets us fit perfect oracles into our model of games.

We reverse the roles of the challenger and the adversary in this situation, to a certain degree. The oracle is actually the adversary here! This is so that when we have a reduction from an oracle, we can send queries to the oracle and receive back responses. This also allows on using oracles which are not necessarily efficient, because reductions wrap around all adversaries, not merely the efficient ones, since a reduction itself makes no reference to the internal operation of an adversary.

Now, often, we want to allow multiple queries to the oracle, We can achieve this by adding more random queries, and letting the adversary win only if they can answer all queries correctly.

We might also want to make multiple queries in a single phase. We can achieve this by sampling multiple random $q$ points at once, sending them all, and receiving multiple responses, which we require to all be correct.

Another technicality is that we want to be able to not query the oracle at a given phase. When we compose the oracle in parallel with another game, we’d like to be able to not have to make an oracle query at every phase.

The essence of achieving this is to be able to query a trivial point $\bullet$, and for the adversary to respond with a trivial response $\bullet$, naturally, we would like the adversary to not be able to win by responding $\bullet$ otherwise.

$$ \begin{aligned} &\text{cheat} \longleftarrow 0&&\cr &b \xleftarrow{R}\{0, 1\}&&\cr &\text{if } b = 1 &&\cr &q \xleftarrow{R} \mathcal{Q} &&\cr && \xrightarrow{q} &\cr &\text{else} &&\cr && \xrightarrow{\bullet} &\cr &\text{fi} &&\cr && \xleftarrow{r \in \mathcal{R} + \{\bullet\}} &\cr \end{aligned} $$

With $\text{Adv} := P[f(q) = r \lor b = 0] \stackrel{?}{=} 1$. Note that we consider $f(q) = \bullet$ to always be false. Because, once again, this only gives a non-zero advantage to adversaries which are always correct, this correctly captures the notion that an adversary with a non-trivial advantage at this game is an oracle for the function $f$.

We can extend this in a natural way to multiple phases, and multiple queries in a single phase, and encapsulate all of this under an oracle game $\mathcal{O}_f$, for any function $f : \mathcal{Q} \to \mathcal{R}$.

Using oracles

With this grunt work done, we actually have a very neat way to use oracles. For example, if $A$ reduces to $B$, provided we have access to an oracle for $f$, then we can simply say:

$$ A \otimes \mathcal{O}_f \to B $$

The tensor product does exactly the right thing! We’re constructing an adversary for B, and we’re wrapping an adversary for $A$. But, at each stage, we can optionally query the oracle, and query it as many times as we want during each phase. And, because we’re oblivious to kind of adversary we have for $\mathcal{O}_f$, this works even for functions where no efficient oracle exists.

And, once again, this merely formalizes the syntax we implicitly use when querying oracles inside of security notation diagrams.

Some Cool Category Things

Because we have a notion of morphism between Security Games, i.e. a reduction, we can consider limits and other categorical objects inside this category.

Terminal Object

There’s a trivial security game wherein only trivial messages are sent, and in which we set the advantage to always be $1$. Clearly, this object is terminal in the category of security games. We can create a morphism in the right direction, simply by ignoring the adversary, and always sending trivial messages. And, since the advantage is $1$, advantage growth clearly holds as well.

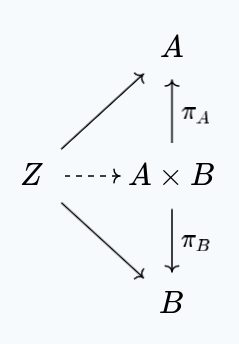

Product of Games

The product of $A$ and $B$ is the closest game to $A$ and $B$ with reductions to both $A$ and $B$. That is to say, it has the weakest adversaries out of all the games with reductions to both $A$ and $B$. That is to say, for each other game $Z$ with reductions to $A$ and $B$, we have a unique morphism to $A \times B$ making the following commute:

Concretely, adversaries for $A \times B$ need to be capable of winning both $A$, as well as $B$. To accomplish this, our messages will actually be $R_i = R^A_i + R^B_i$ and $Q_i = Q^A_i + Q^B_i$. That is to say, we send messages that belong to one of the games at each point.

At the start of the game, the challenger flips a coin, selecting one of the two games to play at random. From that point on, the state of the challenger follows the state of that game, and they send messages from that game. If they receive responses from the wrong game, the adversary automatically loses. Formally speaking though, our challenger states are also $C_i = C^A_i + C^B_i$. We have a natural definition of advantage, by using: $\text{Adv}_\times := \min(\text{Adv}_A, \text{Adv}_B)$. This guarantees growth of advantage in reductions.

Intuitively, this is an adequate definition, because an adversary that can consistently at this game must be able to consistently win at either game, since they don’t know which one they’ll be playing in advance.

Co-Product of Games

The dual notion of the product is the sum of two games, which should be winnable by an adversary which can win either of the games, but not necessarily both of them.

Surprisingly enough, the structure of $A + B$ is the same as $A \times B$, with one small change: instead of the challenger choosing which game is played, at random, the adversary chooses, by sending their choice at the start of the game. We also need to choose $\text{Adv} := \max(\text{Adv}_A, \text{Adv}_B)$. You might think that you could still get away with choosing the minimum, but this doesn’t work, because the coproduct of a game $G$ with some unwinnable game $U$ should be a winnable game $G + U$, so that we have a reduction $G \to G + U$.