Universal Properties and Adjunctions

“Free” constructions are abundant in Algebra, and are actually examples of Adjunctions. Specifically, we have an adjunction:

$$ \bold{Set} \xtofrom[?]{F} \bold{Alg} $$

Where $F : \bold{Set} \to \bold{Alg}$ is the free functor from the category of sets to this category of algebraic structures, and $? : \bold{Alg} \to \bold{Set}$ is the forgetful functor, which forgets the additional algebraic structure.

Usually, this universal construction is presented a bit differently, but is equivalent to the notion of adjunction.

Free Groups

As a concrete example, take Free Groups. Given a set $A$, the free group $F A$ is usually defined with a universal property:

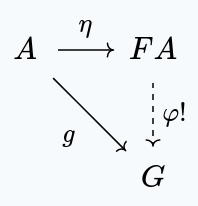

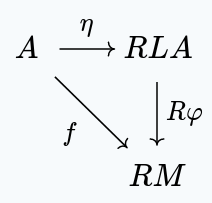

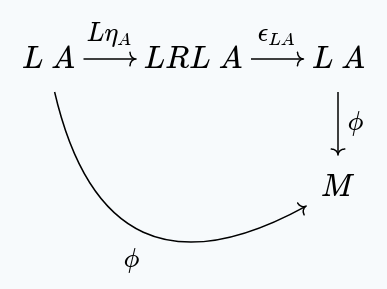

There is a group $F A$, and a set function $\eta : A \to F A$ such that for any other group $G$ and function $g : A \to G$, there exists a unique group homomorphism $\varphi! : F A \to G$ making the following diagram commute:

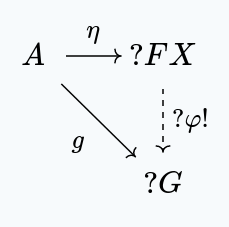

Of course, when talking about the interaction of morphisms and objects from $\bold{Grp}$, we really mean their images, under the forgetful functor $? : \bold{Grp} \to \bold{Set}$. Being explicit, we get the following diagram:

We can characterize this object $F A$ as being an initial object in the slice category $A \downarrow ?$ (where $A : 1 \to \bold{Set}$ is the functor sending every object to $A$, and every morphism to $1_A$).

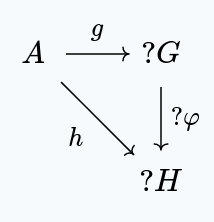

The objects consists of a choice of group $G$ and set function $A \to ?G$, and the morphisms are group homomorphisms $G \to H$ making the following diagram commute.

It’s clear that the initial object in this category is the free group $F A$, along with the morphism $\eta : A \to ? F A$.

Adjunctions

It turns out that this characterization is implied by the adjunction:

$$ F \dashv \ ? $$

The “primal” characterization of an adjunction $L \dashv R$ is that there exists a special binatural isomorphism between the two functors:

$$ \mathcal{D}(L -, -) \cong \mathcal{C}(-, R -) $$

A more convenient (and entirely equivalent) characterization is that of two natural transformations:

$$ \begin{aligned} \eta : 1 \Rarr R L \cr \epsilon : L R \Rarr 1 \end{aligned} $$

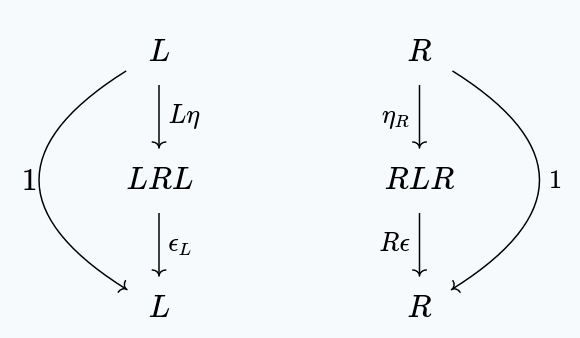

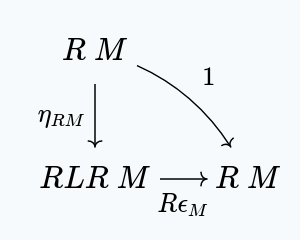

Satisfying these two relations:

which we call the left and right “zig-zag identities”.

Implying the Universal Property

With this adjunction in place, we can show that $(L A, \eta_A)$ is the initial object in the comma category $A \downarrow R$, for any object $A$.

This is a fun series of diagram chases.

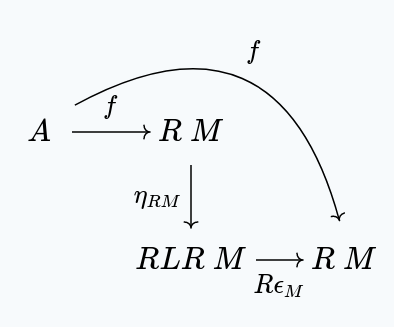

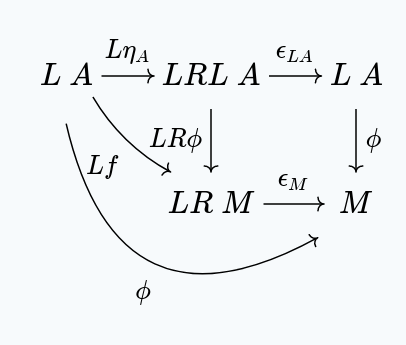

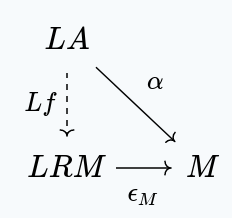

First, we show that there is a morphism to the other objects in the comma category. Given $(M, f : A \to R M)$ some other object in $A \downarrow R$, we provide a morphism $\varphi : L A \to M$ such that this diagram commutes:

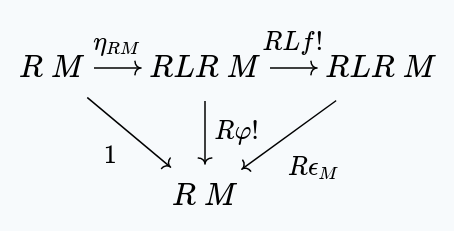

Applying the right zig-zag identity at $M$, we get this commuting diagram:

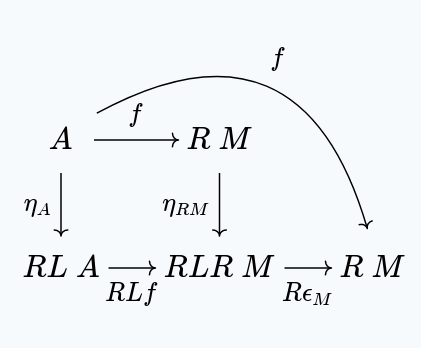

We can compose this with $f$ to get:

But then, by naturality of $\eta$, we have:

And then $L f \ggg \epsilon_M$ is our $\varphi$. Since $R$ is a functor $RL f \ggg R \epsilon_M = R (L f \ggg \epsilon_M)$

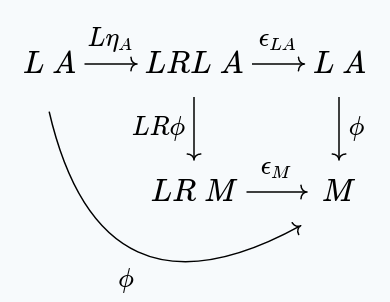

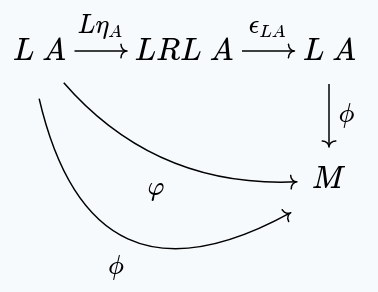

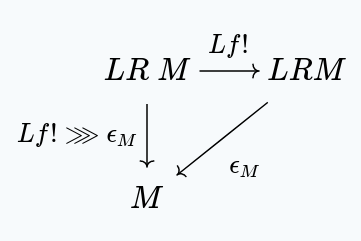

Next, we show that this function is unique. In other words, if $\phi : L A \to M$ with $\eta_A \ggg R \phi = f$, then $\phi = \varphi$.

We start with:

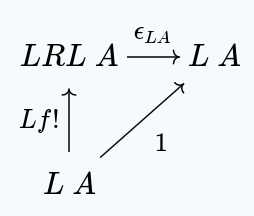

Then, we apply the left zig-zag identity, to get:

By naturality of $\epsilon$, we get:

But, since $\eta_A \ggg R \phi = f$, we have:

But, by definition $\varphi = L f \ggg \epsilon_M$, giving us:

In other words $\varphi = \phi$.

The Dual Construction

If we take the opposite functors $L^{op} : \mathcal{C}^{op} \to \mathcal{D}^{op}$ and $R^{op} : \mathcal{D}^{op} \to \mathcal{C}^{op}$, we have:

$$ R^{op} \dashv L^{op} $$

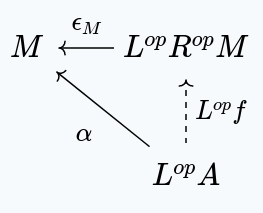

Using our previous result, we get that for any object $M$ in $\mathcal{D}^{op}$, $(R^{op} M, \epsilon_M : M \leftarrow LR\ M)$ is initial in the slice category $M \downarrow L^{op}$

Of course, this is the same thing as saying that $(R M, \epsilon_M)$ is terminal in the slice category $L \downarrow M$. In other words, for any object $A$ in $\mathcal{C}$, with a morphism $\alpha : L A \to M$ in $\mathcal{D}$, there exists a unique $f : A \to R M$ such that this diagram commutes:

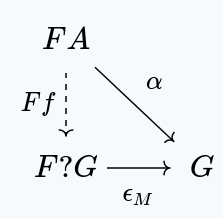

Concretely

Back to the example of free groups, we have the following situation:

Ultimately, this just expresses the fact that a group homomorphism out of a free group consists first of replacing each of the seeds with an element of $G$, and then reducing the free algebraic structure using $\epsilon$.

The Other Direction

We can also go in the other direction. Let $L : \mathcal{C} \to \mathcal{D}$, $R : \mathcal{D} \to \mathcal{C}$ be functors. If we have parameterized functions (which we don’t yet assume to be natural) $\eta_A : A \to RL \ A$ for any object $A$ in $\mathcal{C}$, and $\epsilon_M : LR \ M \to M$ for any object $M$ in $\mathcal{M}$, such that $(L A, \eta_A)$ is initial in $A \downarrow R$, and $(R M, \epsilon_M)$ is terminal in $L \downarrow M$, then we have an adjunction:

$$ L \dashv R $$

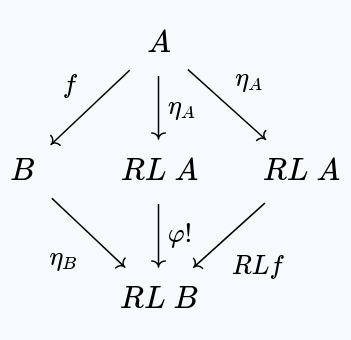

First, $\eta$ is natural:

The right and left triangles both commute, since they make use of the unique $\varphi!$ that must exist whenever we have a function $A \to R M$, for some $M$.

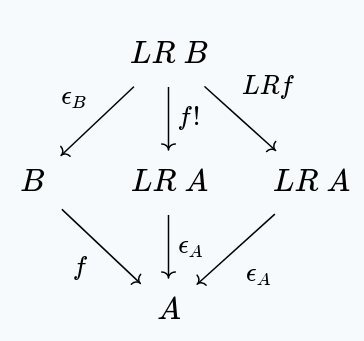

Secondly, $\epsilon$ is natural:

The left and right triangles both commute, making use of the universal property of $LR \ A$. (The argument is similar to before, of course).

Now, for the zig-zag identities.

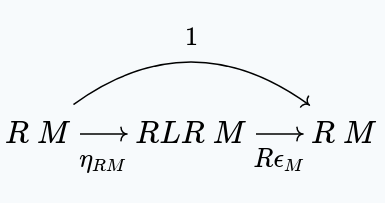

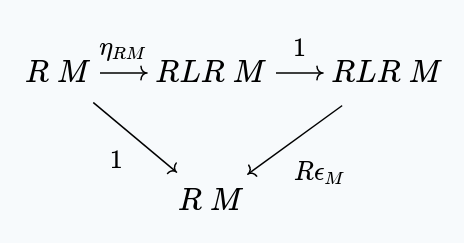

Let’s start with the right zig-zag identity, for some object $M$:

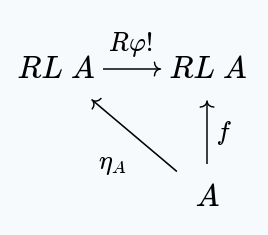

If we take $1 : R \ M \to R \ M$, we have a unique $\varphi!$ such that:

by the universal property for $RL$.

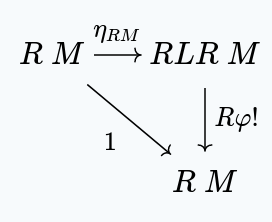

For any $\varphi : LR \ M \to M$, we have a unique $f!$ such that:

by the universal property for $LR$.

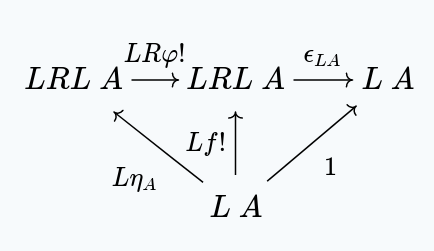

Combining the first diagram, with the image under $R$ of the second, we get:

But, $Lf! \ggg \epsilon_M$ satisfies the universal property of $\varphi!$, which is unique. This means that $\varphi = Lf! \ggg \epsilon_M$.

We then have:

But clearly, $1$ satisfies the universal property of $f!$ in this situation, which means $f! = 1$. This gives us:

And so the right zig-zag property is satisfied.

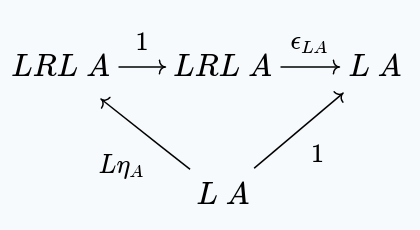

For the left zig-zag property, we use the same strategy.

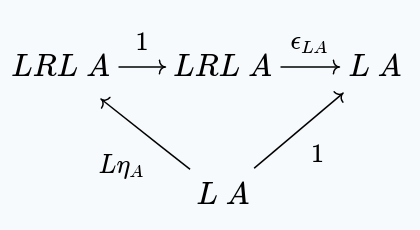

Given any object $A$, in $\mathcal{C}$ we want to show:

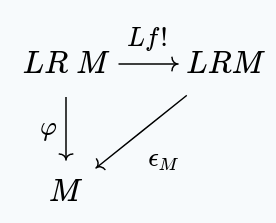

We have the following diagram:

With the unique $f!$ satisfying this diagram existing because of the universal property of $LR$.

Similarly, for any $f$, we have:

because of the universal property of $RL$.

Combining both diagrams, we get:

A similar argument as last time shows us first that $f! = \eta \ggg R\varphi!$, and then $\varphi! = 1$, giving us:

and so the left zig-zag property is satisfied.

Conclusion

Given functors $L : \mathcal{C} \to \mathcal{D}$ and $R : \mathcal{D} \to \mathcal{C}$, these statements are equivalent:

- $L \dashv R$

- $\mathcal{D}(L -, -) \cong \mathcal{C}(-, R -)$

- There exist $\eta : 1 \Rarr RL, \ \epsilon : LR \Rarr 1$ satisfying the zig-zag identities

- ($\forall A \in \mathcal{C}, M \in \mathcal{D}$) $(RL A, \eta_A)$ is initial in $A \downarrow R$, and $(LR M, \epsilon_M)$ is terminal in $L \downarrow M$.

In this post, I only proved $3 \iff 4$. $1 \iff 2$ by definition, and $2 \iff 3$ is well known.