Spaced Repetition for Mathematics

Recently, I’ve been experimenting with using spaced repetition for self-studying “advanced” mathematics. This post goes through my motivations for adopting this system, as well as a few techniques I’ve used in adapting it to mathematics.

What is Spaced Repetition

After reviewing a fact, or re-working some problem, you’re more familiar with it. If you’re quizzed about that problem soon after, you’ll be able to effortlessly recall the solution. But, if you don’t visit this problem for long enough, you’ll eventually forget this solution. The better you understand something, the longer it takes to forget it.

The idea behind spaced repetition is to reintroduce ideas and problems right before you forget them, forcing you to engage with the idea, and refreshing your memory. This is spaced, because the periods without recall get longer and longer, as your knowledge becomes more and more solid

A Spaced Repetition System, or SRS, for short, is some piece of software, or even analog system, that allows you to create “flashcards” which include some form of prompt, and some form of answer. The system then quizzes you on these cards, so that you’re able to recall the information when prompted. It repeats these quizzes in a spaced way, to try and keep the information fresh, while spacing reviews out as you get better at recalling that information.

In practice, the system prompts you for some information, and then you reveal the answer, and mark that information as recalled or forgotten. If you recalled the information correctly, then the waiting period until you see that information again gets longer. If you fail, on the other hand, then the waiting period shortens, or even gets reset, in some systems.

Why Spaced Repetition?

The promise of an SRS is being able to actually keep the information you learn through studying, instead of having it slowly attrition away. A lot of information is “use it or lose it”, and if you don’t actively use some technique or knowledge, you risk just forgetting it. An SRS tries to game your memory, by having you “use it” right before you would forget it.

Personally, I’ve found it a more compelling alternative to note-taking. In practice, I basically never reviewed the notes for courses I took, even if I dutifully gathered notes, like at the beginning of my degree.

I think of a spaced repetition system as a way to actively review your notes and findings in an automated way, so that you don’t spend needless time reviewing things you already know well, or forget to review things that you don’t have a solid grasp on.

Since the system spaces information based on whether you’ve managed to recall that information, it keeps things fresh, without wasting your time.

With this kind of system in place, my “permanent” notes migrate towards pieces of knowledge I want to remember. I still use pen-and-paper notes, but this is more so for engaging with material as I learn it, and not for revisiting later. The SRS takes care of scheduling my revisiting for me.

Easy Applications

An obvious application of SRS, and the place where I first encountered it, was for learning languages. When learning a foreign language, you have a lot of information that you want to memorize. For example, vocabulary is something you’d obviously want to have ready when speaking the language.

Using an SRS for vocabulary is quite simple to understand. You add cards with the word you want to learn, and the translation on the back. You might even add the reverse card as well, in order to be able to translate a word from your native language back to the foreign one.

As you continue to use your SRS, you build up a larger and larger war chest of vocabulary at your disposal. The SRS makes sure you to keep all the vocabulary fresh, even the words that you don’t use everyday.

For Mathematics?

While it’s clear how an SRS would be very useful for learning a foreign language, it’s not clear how it would be applicable to mathematics. Learning a foreign language involves a lot of necessary memorization, but mathematics, especially as you get to a higher level, is less about memorizing identities and formulas, and more so about solidifying broader understanding about different subjects.

If you can rederive some proof, there’s less of a need to have its proof memorized. On the other hand, you do want to have a working understanding of the different concepts involved in a mathematical subject.

When working through some subject, you inevitably have a collection of techniques and properties at hand, since they keep coming up as you move forward.

Having an SRS lets you keep this understanding in place even as you don’t actively work in a subject anymore. Personally, I’d find it a bit of a shame to lose this framework of knowledge as soon as I’m not actively studying some subject anymore. This is especially important for me, since I study mathematics more so as a hobby, instead of it being my full-time occupation. I can imagine this being less necessary if you spend your days entrenched in some field of mathematics.

Different Types of Cards

When preparing cards for mathematics, you want to focus on fundamental understanding, as opposed to surface level facts. The kind of cards you need to make are less evident than for learning a foreign language, where it’s clear what information needs to be committed to memory.

Here are a few types of cards that I use, and have found to be useful.

Definitions

The first type of card is for definitions. As an example, here’s one card I’ve written:

You see the prompt above the divider, and you have to recall everything below the divider.

A card like this helps you remember the definition of a mathematical object.

This is actually the kind of thing you want to memorize verbatim, since knowing the definition of some object is pretty important to be able to use it. Of course, as you’re actively working in some subject, the common definitions will be second-hand, but having them committed to long-term memory is nice when you aren’t actively engaging with the material anymore.

Characterizations

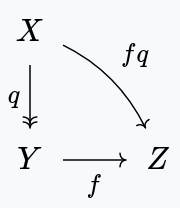

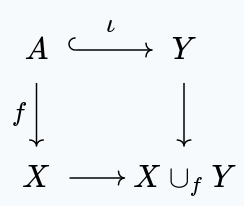

A lot of mathematical objects have concrete definitions, as well as universal properties that characterize them. Knowing the characterization along with the concrete definition can be very useful:

The card could also be less blunt, trying to relate some concrete concept to a more general categorical characterization:

This card is asking the question more indirectly, and also requires connecting the concept of adjunction space with the broader concept of a pushout.

By forcing you to recall the connections between different definitions, this strengthens the understanding of both subjects.

Comparisons

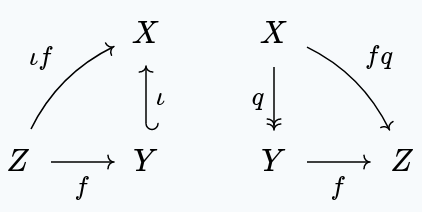

With this kind of card, you have to recall some kind of property, but with less focus on the detail of the property, and more so about drawing a connection between two different concepts.

For example:

You already have cards for each of these properties individually, requiring more detail. This card helps illuminate the similarities between concepts you’ve already learned, reinforcing those concepts at the same time.

Motivations

The idea behind this card is to introduce some piece of intuition, or motivation behind some concept:

This isn’t about recalling the motivation exactly, but rather anchoring a concept in your mind with some ways of thinking about that concept.

Proofs

A lot of the mathematical content of a subject comes forward through the techniques you use to prove things. Because of this, learning the proofs of various things let you understand the subject at a technical level.

Proof Strategies

One type of card is a rough sketch of a proof, where you recall the strategies involved in proving something:

- Divide it into different hemispheres, each of which is the graph of a function

- Project the sphere onto a hyperplane of dimension $n$

The idea here is to keep in mind different high-level strategies for proving some theorem. Having multiple strategies in mind helps reinforce both of them individually, which is a bonus.

This type of card can also include high-level overviews of longer proofs, to complement complete cards for their individual parts.

Actual Proofs

This kind of card is pretty straightforward. You need to recall the proof of some property or theorem:

Then, $(x_1, x_2) \notin \mathcal{R}$, so we have a neighborhood $V_1 \times V_2$ containing that point, and disjoint from $\mathcal{R}$.

Then, $q(V_1)$ and $q(V_2)$ contain $y_1$ and $y_2$, are disjoint, and are open by assumption of $q$ being open.

$\square$

The goal here isn’t to recall the proof verbatim, but rather to be able to rederive the proof with pen and paper. This requires knowing the high level steps,and being familiar with the various properties involved.

You want theorems that aren’t very long here. Very often, I’ll need to split up longer proofs into multiple cards requiring the full proof of some step, and then a higher level card asking for the strategy of the proof overall, assembling the small parts together.

Conditions for Theorems

Whereas the previous kind of cards gives us the theorem, and asks us for the proof, this kind of card gives us part of a theorem, and asks us what conditions we need for this theorem to hold. For example, here’s a complement to the last card, providing an example of this kind of reversal:

This forces you to engage with the statement of a theorem, remembering some of the conditions necessary to make it work. You can even split up the theorem statement in multiple ways like this, each of which reinforces the idea of the theorem in your memory.

Recalling Properties

Another kind of card asks you to recall some property of some object. A good example is recalling equivalent properties:

- $U = q^{-1}(q(U))$

- $U$ is a union of fibers

- For every $x \in U$, $q(x') = q(x) \implies x' \in U$

I’d usually also have a proof for each of the implications involved in proving this, along with a definition card for “saturated set”. By having this extra card, we solidify our understanding of how these properties relate to eachother, and can split up the larger proof of this equivalence into smaller cards, since this overview card serves to glue them together.

Overlapping Information

I try to overlap the information throughout multiple cards, which helps reinforce the concepts involved. This is even better if you use different kinds of cards for the same concept. For example, having a definition card, a characterization card, some proofs, and then recalling various properties.

Having cards that bring about the connections between different concepts is quite nice as well, since it helps to both help recall the properties of various objects, and also to see the broader picture of a subject.

Splitting Information

For definitions, you can usually just make a card verbatim. On the other hand, you can’t exactly copy most proofs down, since they lead to cards that are way too long. Because of this, you have to try and split proofs down to make “bite-sized” cards. One technique I’ve mentioned is to split a large proof into small proof cards for each part, and then create a high level proof overview card gluing them together.

Breaking down larger concepts into smaller chunks is also a great way to engage with the material, since you’re forced to distill and play with the proofs and objects of the subject.

Some SRS Applications

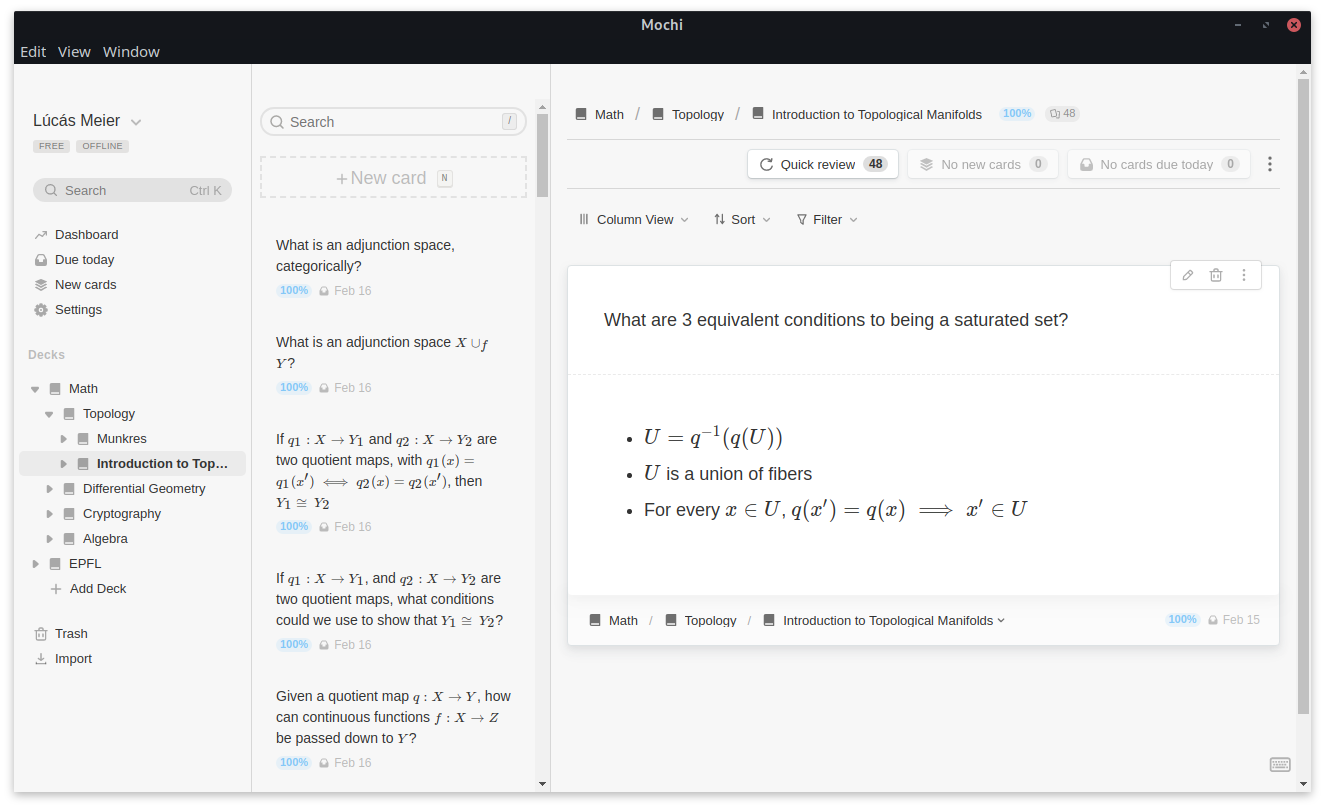

Anki is probably the most popular SRS, and has LaTeX support, as well as images, which are key for mathematics. On the other hand, I personally prefer Mochi Cards, since I find the interface much cleaner, and the latex entry much more seamless:

(there’s also a dark mode, which is neat).

Conclusion

Personally, I’ve been doing this for about a month now, and I’ve really found the benefits to be much clearer as opposed to detailed note taking. Now I feel like I actually get compounding benefits from my notes, thanks to the SRS.

Hopefully this might provide a few ideas for people looking to apply SRS to mathematics. If you’re still skeptical about the benefit of this kind of system, I’d recommend checking out this article, which really inspired me to try applying it to mathematics.